Published on April 1, 2015

By Thomas Van Hare

On September 12, 1962, at Rice Stadium in Texas, President John F. Kennedy spoke these words:

“We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too.”

To get that within the timeline set by Kennedy — to set foot on the Moon within the decade — the challenges facing NASA were many. At the time of the speech, America was just a newcomer to space, working on Project Mercury. Many hurdles lay ahead. The country would go through Project Gemini and dozens of other programs, operations, and spaceflight efforts before Project Apollo would touch down on the surface of the Moon.

In 1966, just four years after the President’s speech, NASA launched the first Lunar Orbiter mission to survey and photo map Moon’s surface in great detail. The goal was that with the imagery captured, NASA’s science teams could select the best possible landing sites for the upcoming Apollo missions.

The Spacecraft and Camera

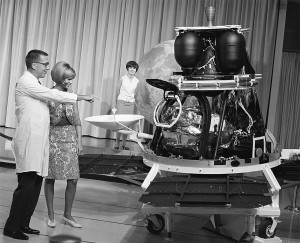

The Lunar Orbiter missions relied on five space flights of a single design — Lunar Orbiter I through Lunar Orbiter V. The five spacecraft involved were launched in rapid succession from the summer of 1966 and into 1967, one of many NASA missions that are known but not widely discussed.

The Lunar Orbiter spacecraft itself was developed by Boeing and Eastman Kodak. It utilized many early satellite design features. For the camera, which was the key to the operation, Eastman Kodak developed a system based on special cameras used by the National Reconnaissance Office’s U-2 and SR-71 spy planes.

The problem was that film could be developed in labs back on the ground after those aircraft landed after each mission. Clearly, that wasn’t an option for film shot while in Lunar orbit and returning film canisters to Earth would be troublesome, add significant weight to the launch package and result in imagery that was not very timely. To address that challenge, Eastman Kodak built an automated film developing system that carried into space along with the camera. In this way, the film could be developed while in Lunar orbit, then scanned by a photomultiplier and transmitted, line by line, back to a ground station on Earth. It was the early equivalent of a FAX machine from space to Earth.

A Surprising Idea

Following the summer launch of Lunar Orbiter I, it wasn’t long before NASA’s scientists were receiving reams of photographs over their “space FAX” from Lunar orbit. Despite their familiarity with the technical specifications and resolution of the imagery, the scientists were astonished at the quality of the images they received. Certainly, the results were not “picture perfect”, but they were more than what was needed. In fact, the actual images proved to be extraordinary.

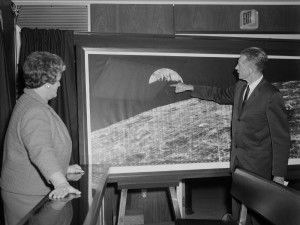

It wasn’t long before the landing site evaluation team had transitioned from looking at images one by one on their desks to setting them out on the floor of a large room so that they overlapped into a seamless surface. Then, being careful not to scuff the images, they walked right on the pictures themselves. From that aspect, the scientists could look down at the surface of the Moon as if they were soaring directly above it. Furthermore, the scale of the landscape was more apparent. Large features that would have been invisible to the eye when looking at photos one at a time suddenly became visible when “stitched” together into a vast floor of imagery.

In the end, the Lunar Orbiter missions mapped 99 percent of the Moon’s surface to a resolution of 60 meters (about 200 feet). The rocks, craters, hills, and ridges of the Moon’s surface were displayed in never-before-seen detail. A set of landing sites were selected, including the very place where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin would first set foot on the Moon in 1969.

Yet during the very first mission of the series, a new idea was suddenly raised — could the Lunar Orbiter be turned from its vertical position to point its camera to peer instead across the surface of the Moon and back toward the Earth itself? If so, the mission would be able to capture mankind’s first photograph of our own planet as seen from deep space.

It was an opportunity that clearly couldn’t be missed — if it could be done.

The Quandary

Yes, that’s right — if it could be done. And in that, the engineers at NASA faced a serious problem. Nobody knew if the spacecraft could be successfully turned sideways to look across the surface of the Moon rather than straight downward. Further, nobody knew whether it could be righted again afterward to continue its photo mapping mission. While it looked possible on paper, the maneuver was something that nobody had planned for. As NASA had learned the hard way countless times in its quest to take man into space, things that you assumed often turned out to be wrong — sometimes with terrible consequences.

Additionally, there was no mission-critical reason to take the photo at all. Thus, it seemed that it all came down to a simple question of art vs. science. Was a photo with almost no scientific value worth jeopardizing the scientific goals that were at the very heart of the mission?

The debate on the subject touched on many topics. One topic addressed the matter of man coming to grips with our place in the universe. There were also the public relations aspects of the photo to consider. Additionally, there was the question of how the failure would be addressed if the spacecraft couldn’t right itself and the rest of the mission of Lunar Orbiter I would be canceled.

The mission engineers also knew that if the spacecraft couldn’t be returned to its vertical position and continue its mapping mission of the Moon’s surface, they would have to take the blame — personally. They knew too that they might even lose their jobs over the debacle that almost certainly would follow such a failure. Such risks would be taken not out of scientific necessity but out of what some might call “artist whim”. Congressional hearings might follow to the embarrassment of many.

Millions of dollars of appropriations were at stake — and that meant too explaining the decision gone wrong, if it came to that, not just to the US Congress but to the public as well. Yet it was in that very thought that the justification for the decision was ultimately made. NASA would not only take the photo but also share it with the key members of the US Congress who were supporters of NASA’s annual appropriations.

Politics, a late-comer to the debate, had won out over both art and science.

The Photo

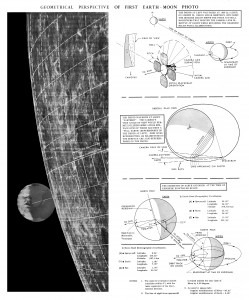

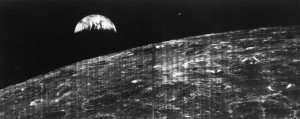

Finally, in August 1966, while the team held their breath, the commands were sent to turn the Lunar Orbiter sideways and aim its camera back at Earth. Rather unceremoniously, as is often the case in the greatest endeavors of science, the photo was taken. As it was developed and transmitted back to Earth, the commands were sent to return the spacecraft to its vertical position. It worked.

There were three victories that day. First, the spacecraft did return to vertical allowing it to continue the mapping mission, much to the relief of everyone involved. Second, the Congress so loved the photograph that they asked for poster-sized copies to distribute to constituents and to hang on their office walls, sealing further support for NASA’s mission — and appropriations.

And fourth, above all, the photograph exceeded all expectations and hopes. In fact, it wasn’t until years later when Apollo 17 shot the now famous “Blue Marble” image on December 7, 1972, that this first photograph of the Earth from deep space would be surpassed in its majesty and power to inspire. This first image of Earth from Lunar Orbiter I was quickly dubbed “the picture of the century” and, perhaps even more astonishingly also called, “the greatest shot taken since the invention of photography.”

President Kennedy had ended his speech four years earlier with these words — more fitting than ever as the summer of 1966 drew to a close:

“Well, space is there, and we’re going to climb it, and the moon and the planets are there, and new hopes for knowledge and peace are there. And, therefore, as we set sail we ask God’s blessing on the most hazardous and dangerous and greatest adventure on which man has ever embarked.”

In the end, brought home with a single inspiring photo, the engineers and flight controllers at NASA got it right as they would many times more in the greatest quest in history, to set foot upon the Moon — for all Mankind.

One More Thing

Take a moment to transport yourself back in time to what is probably President Kennedy’s greatest speech — when he committed the nation to land a man on the Moon within the decade.

To Watch the Video, Click Here =>

I was a boy of 7 years old at the time. I started to fly Estes rockets in my back yard after asking my father if it would be okay as I did not want to interfere with the space race. My father smiled and said he thought NASA would be okay with my launching rockets in our backyard in Michigan. I was also glued to every launch and every mission — and I still do that to this day! 🙂

Really great article with wonderful graphics and picture, explaining the mission. Thanks!

This was a challenging and exciting time to work at NASA…

If people only knew all the technological advances that are available in today’s world that had their start at NASA in the 60’s…

We would still be in space with an active program of exploration…

I was there…

Ed

Thanks again for another great article. You brought back so many memories growing up in this time. And I agree with Ed. So much of our modern world uses spin off technology from NASA and the space program.