Published on August 8, 2016

by Thomas Van Hare

On the home front during the Great War, 100 years ago, 3D viewing of photographs was very popular, the most common means being with a Holmes Stereoscope. Viewers simply inserted a stereo photo card into the slot on their Stereoscope, then peered through the eye lens. Thus, they could see the scene as if they were there, with their own two eyes — albeit in black and white.

The Library of Congress in Washington, DC, has thousands of stereo photo cards in its collection. A handful feature aircraft from the Great War (1914 to 1918), giving us a fascinating view of the battlefield as it was — if in sepia tone and black and white.

Men and Machines

Five stereo photo cards from the collection depict the men and the aeroplanes of the day — simple photos that seem dated in their composition and yet come alive when viewed with a stereoscope or by the above methods.

The first juxtaposes a prewar cavalry reconnaissance unit with a single airplane seen flying overhead. The airplane was an extraordinary reconnaissance innovation, providing wider, better, and more timely coverage of the battlefield than any lightly armed force of men on horseback could ever hope to achieve. When the Germans first advanced into France in 1914, they were preceded by 60,000 cavalry reconnaissance troops — virtually all were lost in the first months of the conflict. Airplanes offered a much better solution to the challenges of the evolving battlefield, at much less cost, both in budget and in lives lost.

The second card provides a fascinating view of a French bomber readying for take-off, with its vast expanse of wings and wiring providing an ideal subject for 3D stereoscopic viewing. In the notes on the back of the image, the publisher of the photo poetically describes the airplanes of the era as “Hornets of the Blue”.

One of the cards shows a pair of U.S. observation planes at an unidentified location in France, probably taken in 1918. The publisher of the photo notes on the back of the print that, “Today, the observation airplane is the eye of an army. Observation planes carry two men, a pilot, and an observer. The pilot runs the machine’ the observer, telescope in hand, scans the enemy trenches and the terrain for miles in their rear.”

Another photo card shows a French aeronautical advisor, apparently sent to Fort Monroe, Virginia, to explain the Nieuport 17 Bébé to the US Army’s airmen. The identity of the individual, “Lieut. LeMaitre”, is revealed, but we find no other information about him, nor his trip to the USA other than what the publisher of the photo wrote on the back: “Both England and France sent some of their aviation specialists to the United States for the purpose of instructing American officers. Famous French aviators arrived here to help in the training of the 10,000 men needed to conduct aerial operations against the German fleet and U-boat bases. Many of these men wore decorations received for exploits in naval battles and some bore scars from encounters with German airplanes.”

The next stereo photo card depicts soldiers watching a scene of aerial combat overhead. The publisher wrote at length: “One might easily imagine that we are looking here at a peacetime crowd of spectators at an exhibition of ‘stunt flying’, so intent are the faces of these Italian soldiers as they gaze into the sky. But the spectacle upon which they are looking is far more thrilling than any ordinary exhibition, for here two aviators, skilled in all the tricks of their perilous profession, are measuring their courage and wits against one another in a battle which will almost certainly end in the death of either the Italian or the Austrian flyer…. The Italian airmen were famous for their skill and daring and they gained many brilliant victories over the Austrian and German aviators, so it is probably no tame affair upon which these Italian soldiers are looking as they stand absorbed in the street of this little town behind the lines.”

The View from Above

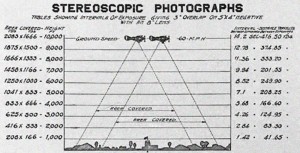

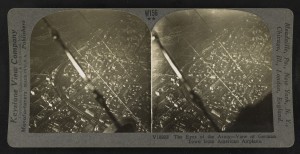

The collection even holds two stereo photo cards that depict scenes taken from airplanes. Aerial photography of the trenches was done with stereoscopic equipment, creating the interstitial distance by taking timed photos as the plane flew overhead. By placing the resulting prints side by side so they can be viewed with a stereoscopic apparatus, a lot of hidden details emerge.

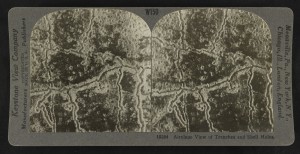

On the first of these two photo cards, the name of the town shown is not revealed. These leaves us to wonder — was this even Germany? What the publisher did write was this: “There were no impassable trenches in the skies, no charted lanes beyond which lay destruction. The airplane roamed the sky at will, sometimes over enemy trenches, sometimes scouting miles to the rear, sometimes hovering over rail heads or dropping bombs on supply stations. The only thing that could bar its progress was an enemy plane. Hence the battles for supremacy in the air…. Daily the planes soared aloft, separated, and shot away to spy out the land beneath, each having its appointed section to cover.”

- “The eyes of the army, view of German town from American airplane.” Gelatin silver print, mount 9 x 18 cm, taken between 1914 and 1918, published in 1923.

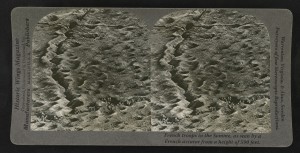

The shell-pocked front lines were a horrific sight, even from above. Stereoscopic photographs allowed even the slightest elevations of the land to be discerned, though translating that knowledge to the battlefield proved a difficult challenge from the beginning of the war to its end. As the publisher wrote of this photo: “But here by the click of a camera shutter, the airman secures the map of the whole area and can carry it back to be examined at leisure behind his own lines by men skilled in deciphering the meaning of every detail which the photograph shows. During the war photographs such as this of the hostile areas were taken in untold thousands by the daring aviators of both sides, often in ‘mosaics’, which could be fitted together so as to show a whole extensive territory.”

Viewing Techniques

To view the above stereo photos in 3D, you can either print them out and use a stereo viewer or, for those who want to learn a bit about stereo photo interpretation, you can view them with the “cross-eyed method”. Just look at the image and cross your eyes, focusing on the ‘third image’ that will appear between the two images on the outside. If you can focus on that, you’ll see the result in 3D. This method is widely practiced in the old days of stereo photo interpretation by military analysts.

Final Thoughts

There were thousands of photographs of the front taken from the air, yet most are lost to us today. No doubt, they were either destroyed or put in archives that may never be opened again. At least a handful of photographs, in stereo views, have survived. These can be seen today because they were reproduced by a civilian company that sought their sale to the general public, those who had their much loved Holmes Stereoscopes at the coffee table.

Just after the end of the war, a French Naval pilot, Jacques Trolley de Prévaux, made a movie from his airplane, flying over the destruction of the Belgian town of Ypres and showing the shell-pocked battlefield of Chemin des Dames.

His film is a haunting reminder of the true cost of war.

Bonus Photo

By applying modern computational dimensionality concepts to a portion of one of these old photographs, we can create a reasonable 3D facsimile of the Somme battlefield as it was seen by that unnamed French aviator in 1916 — fought exactly 100 years ago. Please let us know if you experience the added dimensionality by posting a comment below!

Great article. Very interesting, and shows yet another light on man’s power to invent if needed.

I believe the film was made from an airship rather than an aeroplane and that he filmed much of the Western Front, not just over Ypres.