Published on October 3, 2016

By Thomas Van Hare

Almost exactly one hundred years ago, the world’s first tanks rolled onto the battlefields of the Somme. Amazingly, the first use of airplanes to support tanks while on the attack happened from the very start — on the first day that tanks saw combat at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette. This is their story — and the story of the bravery of those who fought in one of the darkest battles of the Great War in 1916.

On September 15, 1916, Britain’s newest innovation — the tank — deployed onto the battlefields of the Somme. The Germans called these new super weapons, “The Devil’s Chariots”, as they were virtually unstoppable — unless, of course, they broke down, got stuck in a ditch or trench or rolled into a shell hole and couldn’t get out.

Like the early tanks, aerial warfare too was still in its infancy. Military airmen struggled to simply fly, let alone employ their flimsy, fabric and wooden biplanes and early monoplanes to any great effect. Many airmen died in crashes, not even from combat with the enemy. Piloting skills were poor. Engines were unreliable. Airplanes were prone to structural failure. By modern standards, flying in World War I, then called the Great War, was a crap shoot. For many airmen, life expectancy “Over the Front” was measured in days and weeks.

At the start of the Great War, the airplane was used just in reconnaissance missions. Later, it was employed in bombing enemy targets, including in special missions to drop leaflets. The next logical step in air warfare was combat between aircraft. At first, reconnaissance planes took shots at one another with pistols and rifles that they carried on board. Then, by the beginning of 1916, the earliest pursuit planes were in the air. They hunted the reconnaissance planes and bombers, usually alone, but then soon learned to fly in packs, hunting enemy aircraft. As the air forces grew and the numbers of planes multiplied, pursuit planes began hunting one another. What had started as a gentleman’s war between pre-war pilots who often knew one another was quickly overtaken by an industrial-scale battle for control of the air.

Ground attack missions soon were tried and a new word was coined — “strafing”, which meant to dive low over the trenches, which were vulnerable from above, and shoot one’s machine gun at the enemy soldiers down “in the mud”. The soldiers in the trenches were terrified. Soon, the pilots of both sides took to strafing the trenches regularly. The French innovated a new weapon, called flechettes, which were tiny metal spikes with fins that when dropped from on high, could kill those unlucky enough to be in the open. Indeed, 1916 was a seminal year in the development of combat uses of the airplane.

Airplanes Supporting Tanks

Mr. W. Beach Thomas, a writer with the Daily Mail, was assigned to cover the Royal Flying Corps during the Somme Offensive. On or about September 16th, he wrote regarding his first knowledge of tanks on the battlefield. Rather breathlessly, he related:

“Such a battle has too many parts to suffer description. The battle in the air has perhaps never been equaled. The prisoner, who complained of the ‘Tanks,’ concluded by saying that they were anyway better than the aeroplanes. How many fights there were no one knows. I believe we destroyed more than the 13 enemy planes officially recorded. The enemy kite balloons bob up and down in terror after the havoc in their ranks.

“Village after village just behind the lines was bombed, and to complete the work the airmen came down low enough almost to stroke the back of the ‘Tanks,’ quite low enough to empty their bullet-drams at the enemy’s infantry. The Archies’ fired at them in vain, though, as it seemed to me scores of our craft were perpetually rolling across the sky on ball-bearings of shrapnel cloud. From half an hour before dawn till sunset there was a constant sky patrol enemywards and a continuous chassé over our advancing troops and the enemy’s batteries. Every headquarters that day rang with aircraft messages.”

So it seems that from his view, the tanks too were an extraordinary achievement, and the airmen were flying over them closely on their own missions to support the advance of the ground troops. His reporting dated from the first days when tanks were employed in the Somme Offensive that September 1916. Nonetheless, his article doesn’t quite show a purposeful relationship between tank warfare and air attack — it falls just short, though the two are in the same battle at the same time.

His declarations of extraordinary success in the air were also perhaps overstated. It was at precisely this time that the German Jastas were arriving with their new Albatros D.I and Halberstadt D.II aircraft, and scoring more and more kills. These were planes that vastly outclassed the B.E. 2Cs that formed the bulk of Britain’s air power. Still, the RFC had massed its aerial forces and was flying thousands of missions over the Somme area. The Germans simply could not match the Allied powers’ aerial intensity during the battle.

The First Air Support of a Tank Advance

It was at the Battle of Flers-Courcellete that the first air support of a tank advance took place, though it was certainly more a case of happenstance than plan. The tanks’ mission was to support the advance of the British 4th Army toward Flers, Belgium. On September 15, the first tanks entered battle. There were just 49 available. Of those, just 32 actually reached the Front to participate in the first attack. In the days after, all were engaged, though many were destroyed, abandoned or stuck in the mud, day by day as the battle progressed.

The British commanding general in charge of the tanks, General Henry Rawlinson, known as 1st Baron Rawlinson, at first erred in his use of his new super weapon. He split the tanks up to fight individually across the entire front, rather than concentrating them together into a powerful “fist” that might have punched through the enemy lines and advanced rapidly. Nonetheless, each tank employed in this fashion was dramatically successful.

The German soldiers had never seen such machines. There seemed little to not defy the armored hulks that bristled with four or more machine guns or cannons. The tanks, despite being spread across the front in small groups, were effective, all the more so as they were supported by following infantry when attacking.

As a general rule, the Allied advance proceeded steadily, if slowly, against the German defenses. The tanks could, over roads, make a maximum speed of perhaps 4 mph. Over the muddy ground of the battlefield, they were usually advancing at just 1 mph or 1 1/2 mph. It was painfully slow going.

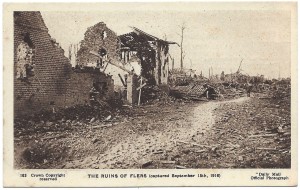

With the tanks, the Allies planned to advance into Flers itself and take the territory to the north and west of the town. The town was a bombed-out wasteland of collapsed buildings, rubble, and the ghostly shapes of tree stumps in a wider muddied, shell-pocked landscape. Hopes that the German Army would disintegrate entirely in the face of the new tanks had already proved overly optimistic even if the tanks were powerful assets on the battlefield.

Facing the new tanks, the Germans had little option but to retreat, which they did in reasonably good order. Once back, they regrouped to fight, moving trench line by trench line, as the Allies advanced. As a general rule, the Allied forces’ progress of the advance was stopped when the tanks got hit by artillery fire, broke down, or got stuck in shell holes, trenches, or ditches. The Germans counter-attacked when the opportunity was right, and this further slowed the advance.

Another writer, this one for the Daily Telegraph and named Philip Gibbs, was assigned to cover the Battle of the Somme. He attended the advance closely and describes the scene in agonizing detail, his prose doing little disguise what must have been a terrible experience for all sides:

“Machine-gun fire rapped out in fierce spasms, and the German ‘Archies’ were throwing up shells which burst all about the planes of our airmen, who came like a flock of birds over the battlefields, flying low above the mists. Long after the sun was at its height there was the white ghost of the moon in the other side of the sky, and it was a strange and beautiful thing to see these aeroplanes of ours shining as though with aluminium wings as they flew through the shellbursts.”

This style of reporting would be echoed over the decades that followed by the many brave Combat Camera crews who would later serve with the British and American air forces, including in World War II — and even right up to today. However, back then the reporter, Philip Gibbs, was perhaps overly laudatory of the bravery of the pilots. This was probably an accurate account given the terrible circumstances of the battle underway, though by modern standards it borders on propaganda:

“They did wonderful things yesterday, those British air-pilots, risking their lives audaciously in single combats with hostile airmen, in encounters against great odds, in bombing enemy headquarters and railway stations and kite balloons and troops, and registering or observing all day long for our artillery. They were out to destroy the enemy’s last means of observation, and they began the success of the battle by gaining the absolute mastery of the air. Thirteen German aeroplanes (since reported by Sir Douglas Haig to be 15) were brought down, and their flying men dared not come across our lines to risk more losses.”

Then Philip Gibbs made note of the first report of an airplane supporting the advance of one of the British Army’s new tanks in the rubble-strewn streets of Flers, Belgium:

“The first news of success came through from an airman’s wireless, which said:—

“A ‘Tank’ is walking up the High Street of Flers with the British Army cheering behind.

“It was an actual fact. One of the motor monsters was there, enjoying itself thoroughly, and keeping down the heads of the enemy. It hung out a big piece of paper, on which were the words :—

“‘GREAT HUN DEFEAT. SPECIAL.’

“The aeroplane flew low over its carcase machine-gunning the scared Germans, who flew before the monstrous apparition. Later in the day it seemed to have been in need of a rest before coming home, and two humans got out of its inside and walked back to our lines.”

Analysis and Aftermath

From historic records, we can report what the writers of the day could not — that the attack at Flers was first overflown by the RFC’s 3 Squadron that morning in their Morane-Saulnier Type L and LA high wing monoplanes. These aircraft were also known as “Morane Parasols”, and, in all, 50 had been supplied to the RFC by the French during 1915. The surviving aircraft were still in use in late 1916 when the Somme Offensive began. By that time, they were hopelessly outclassed by the newer German pursuit planes, yet the RFC kept them in action.

The Morane Parasols were primarily for providing reconnaissance support, but were armed with a single forward-firing machine gun. It was this type of airplane that provided air support to the advance of the Mk 1 tank. The identity of the pilot and which specific plane in 3 Squadron who flew that day to strafe the German soldiers, however, remains a mystery.

On the German side, the soldiers under attack were with the 4th Bavarian and, after a hard morning of fighting, they were ordered in the afternoon to make an orderly retreat to the northeast. They moved quickly and in good order, evacuating Flers, and escaped one mile to the northeast, to the heavily bombed rubble and trenches of the town of Gueudecourt.

The story from the aspect of the tanks is as interesting as the story is from the air. As for the tank that was involved on the “High Street” of Flers, it was one of the 49 Mk 1s that were fielded that day. Specifically, it was Tank No. 538, nicknamed “Dracula” with “D” Company, carrying the identification, D16. All of the tanks of “D” Company had “D” names. Likewise, the tanks of “C” Company had “C” names, like “Cognac”, “Cordon Rouge”, “Chartreuse”, and “Champagne”.

Tank D16 “Dracula” was called a “female”-type tank, as it did not mount any heavy guns, but rather carried six machine guns. The tank was commanded by Lt. Arthur Edmund Arnold, a Welshman from Llandudno. North Wales.

Earlier in the day of the attack on Flers, a creeping artillery barrage had led the British Army’s infantry advance. D16 and the three other “D” Company tanks were assigned, these being numbered D6, D9, and D17. They were a mix of Mk 1s that were “male”, as fitted with two quick-firing 6-pounder naval guns mounted in a sponson on each side of the hull, and four Hotchkiss machine guns, or “female” with carried five Vickers and one Hotchkiss machine guns instead. From the start of the advance, “D” Company’s tanks were left trailing behind the main force as it advanced too quickly for the slowly plodding tanks to keep up.

On belated arrival at Flers, the four tanks of “D” Company split into two components. Tank D16 drove up the road northward on its own directly into Flers, arriving on the outskirts of town at 8:20 am. Although part of the town was already under the control of the British forces, there was still a lot of fighting when the tank belatedly arrived. As it came to the outskirts of Flers, D16 was closely followed and supported by troops of the British 122nd Brigade. By 8:30 am, the other three tanks had also come up the road northward to Flers and they began to work their way up the east side of the town, flanking the German positions in the rubble and ruin of the town.

Just 15 minutes later, at 8:45 am, Tank D16 made its run down the High Street, as reported above, creeping forward while firing all six of its machine guns against the heavily defended German gun positions. At precisely that instant, the 3 Squadron Morane Parasol flew overhead. Seeing the action below, the pilot circled back around and started strafing the German ground forces in support of the tank as it plodded up the street. After the successful advance through the town, the infantry quickly dug in and occupied a position to the north and west sides of Flers and there was a lull in the battle.

The crew of Tank D16 “Dracula”, joining with Tank D18, dismounted to prepare a quick breakfast. Having successfully engaged the enemy, a break was warranted. However, their repast was cut short when a German observation balloon to the north spotted the tanks and reported their position to a German artillery unit. As the first shells came in, the crews abandoned breakfast and returned to their tanks. They quickly repositioned to escape being hit.

In the afternoon, Tank D16 “Dracula” was once again on the advance just north of Flers. In the heat of battle, the tank came upon a wounded New Zealander who was on the ground in the midst of the battlefield. Lt. Arnold ordered that they mount a rescue. Driving closely Lt. Arnold jumped from the tank and ran across the open ground in a daring attempt to rescue the downed man. The German machine gunners, however, were simply too good and Lt. Arnold was himself hit in the knee. D16 “Dracula” then fell to the command of Gnr Jacob Glaister, Jnr., an unassuming prewar motorcyclist who hailed from Whitehaven in Cumberland. Skillfully, Glaister commanded the tank to intercede, blocking the enemy fire, and thereby was able to rescue both men.

Just after lunch, the advance began again toward Gueudecourt. One of the tanks, though not D16, was hit by artillery fire and burned out. In the area between Flers and Gueudecourt, a series of German trenches were steadily overcome and occupied by the advancing British soldiers. By mid-afternoon, however, the advance was ordered to consolidate its gains and prepare positions in the event of a German counter-attack Reconnaissance aircraft from 3 Squadron and others flew extensive support, reporting on no less than 159 artillery batteries that the Germans had brought into action to support their retreat. Due to the reconnaissance reports, 70 of these batteries were targeted with counter-battery fire and 29 were destroyed.

Ultimately, though it survived that day and two weeks after, Tank D16 did not last long in combat. It never left the immediate area of Flers, though it battled numerous trench lines. Finally, on October 1, 1916, it was lost while attacking at Eaucourt l’Abbaye, located only one and a half miles to the northwest of Flers. As it happened, Tank D16, along with one other tank (designation unknown), advanced along the Flers Support Trench heading up toward Eaucourt l’Abbaye. Curving around, it came to approach the abbey from the west. Using their machine guns, the two tanks silenced the German gun positions on the west side of the abbey, but soon became stuck in the shell holes and ditches there. When II Battalion, Bavarian Infantry Regiment 17, counter-attacked from the northwest side, the tank crews could not resist. They abandoned the vehicles, setting fire to them so that they would not be captured.

Final Thoughts

Looking back, it seems that the concept of supporting armored advances with air power is far less modern than we tend to assume. It began by mere chance in the heat of battle on the very first day, at the very dawn of armored warfare. How often it happened thereafter in the Battle of the Somme or the rest of the Great War is a good question. Few reports are available to provide any additional information on the topic.

Overall, the first use of tanks did not go as well as it could have. The tank was a super weapon on the battlefield, yet the commanders knew next to nothing about how to use them. The entire experience was simply seeing the tanks in hurried parades the week before the battle, as the crews were ordered to show their new vehicles to the ground commanders daily, rather than actually preparing for the battle ahead. One tank crewman was later interviewed about his experienced and simply said, “…if only we had been able to reconnoiter… if only there had been some proper practice over ground that was like the Somme, and if only we had had a little more sleep and a little less showing off, what a marvelous story this Somme battle might have been.”

It doesn’t seem that the lessons about combining air power with tank power were learned that day at Flers. It would take years and years before a strategic and tactical doctrine that combined armored assault with air power was born. Then, it would be the Germans, not the British, who would achieve that with their World War II era Blitzkrieg concept. Nazi Germany’s first attacks on Poland set a new standard for air and ground coordination, creating yet a new dawn in tank warfare.

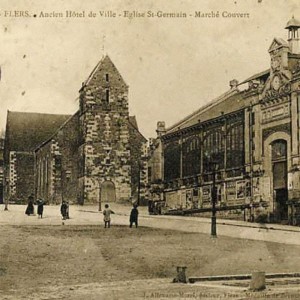

Notably, the “High Street” in Flers, as the British called it, would see tank combat again in World War II when the Allied forces advanced through the town. This was the second time that Flers was completely bombed out and destroyed. Once again, it would be rebuilt and today, Flers is a beautiful small Belgian town well worth a quick visit.

There are a number of war memorials nearby dedicated to the Battle of the Somme, recalling the days when today’s peace was a distant dream.