Published on March 12, 2018

By Ron Miller/io9

The birth of the idea of traveling to other worlds through outer space can be given a specific date: January 7, 1610. That evening, Galileo Galilei first observed the satellites of Jupiter through his telescope. At once, he realized that the planets were worlds just like our own. If they were worlds, then one could travel there as surely as one could take a ship to the New World. Yet such a ship would not be a ship for the seas, but rather one for the skies.

Until Galileo’s discovery, the heavens were thought to be no great distance from the Earth. The Sun and the Moon were thought to be the only material bodies with which we shared the universe. The nature of the Moon was an object of much debate: was it in fact a body like the Earth? Was it something more ethereal? Likewise, the stars, while some were brighter than others, were thought to be at more or less all the same distance from the earth, though just what that distance might be was a matter for discussion.

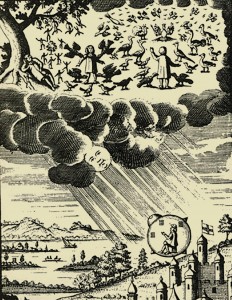

The planets were merely a special class of bright stars that wandered among the other “fixed” stars. Indeed, the word “planet” itself simply meant nothing more than “wanderer.” Otherwise there was nothing particularly unusual about them except perhaps that the “wanderers” didn’t twinkle in the same way as the fixed stars. It was nearly unthinkable that the tiny lights that dotted the night sky might be places to which one might travel. Only the moon served as a destination, but even then, only in a handful of fantasies. Otherwise, the Moon was a kind of a flat disk, a Never-Never Land that went through each of its phases with regularity.

Galileo’s revelation about the planets changed all of that forever. Through his telescope, he could see that Moon was a world as imperfect as our own, with mountains, valleys, plains and hundreds of odd, circular ring mountains and craters. The planets were obviously worlds like the Moon and the Earth. If they were indeed worlds like our own, did not that imply other similarities? Would they not have landscapes and living inhabitants? Surely there would be animal life and perhaps civilizations? Would there be great cities and mighty kingdoms up there in the heavens? If there were, might there not also be great treasures? These questions were far from rhetorical. When human beings looked skyward they no longer saw abstract points of light. They saw the infinite possibilities of new worlds. Galileo lived in the time of exploration, when voyages to the New World were still dangerous and risky and when new lands were being discovered in the Pacific.

At the time of Galileo’s discovery of new worlds in the sky, there were new worlds being discovered right here on earth by Columbus and those who followed his voyage. Only a bit more than a century earlier the continents of North and South America had been discovered quite by accident, lying unsuspected and unknown on the far side of the Atlantic Ocean. By the early 1600s, hundreds of ships and thousands of explorers, colonists, soldiers, priests and adventurers had made the journey to these amazingly fertile, rich and strange new lands. When they learned that an Italian scientist had found the sky to be full of new worlds, too, their interest was cast skyward.

The new worlds of the Americas, which could not even be seen and which existed for the vast majority of Europeans only in the form of traveler’s tales and evocative if imaginative charts, nevertheless could be visited by anyone possessing the funds or courage. Yet here were whole new world — Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and the Moon — that could be seen by anyone with a telescope. They could even be mapped. Surely, by extrapolating from what they knew of the Earth, these whole new worlds would offer unimaginable continents and riches. Yet there seemed no way to touch them! They were like a banana dangling just beyond the reach of a monkey.

It is little wonder that Galileo’s discoveries could not be suppressed, despite the most aggressive efforts of the Church in Rome. Their publication was quickly followed by a flood of space travel stories: Somnium, The Man in the Moone, Voyage to the Moon, A Voyage to the World of Cartesius, Iter Lunaire, John Daniel, Micromegas, A Voyage to the Moon, and countless others. There were poems, songs, stage plays and sermons, all inspired by the possibility of traveling to the new worlds in the sky.

Among the many who gazed up at the heavens with new understand was English Bishop John Wilkins, one of the era’s most famous inventors, Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author. He had no personal doubts that these voyages would eventually be made. He wrote in his Discovery of a New World (1638), “You will say there can be no sailing thither [to the Moon]… We have not now any Drake, or Columbus, to undertake this voyage, or any Daedalus to invent a conveyance through the air. I answer, though we have not, yet why may not succeeding times raise up some spirits as eminent for new attempts, and strange inventions, as any that were before them?… I do seriously, and upon good grounds affirm it possible to make a flying-chariot….”

A great many writers did their best to imagine what such a flying chariot might be like, but they were handicapped by the limitations of the technologies available at the time. The writers of space travel stories before the end of the 1700s were merely groping in the dark: there simply was no method by which a human being could leave the surface of the earth. In all the history of mankind, quite nearly no one had ever left the Earth any farther than they could jump, though a few enterprising inventors had tried tying men to kites and a couple of intrepid adventurers had tried out various winged suits in which to hope to fly (though unsuccessfully).

The first image of what might get one farther into the skies was perhaps created by an Austrian scientist, Conrad Haas. In his book, Kunstbuch [1529-1556], which preceded Galileo by more than half a century, he wrote entirely about the science of rocketry. His writing contains the first descriptions of the use of multi-stage rockets, bell-shaped nozzles, delta fins and liquid fuel. One of the illustrations in the book depicts a large rocket topped by a “flying house,” which Haas clearly meant to carry a passenger. There is no indication, however, that Haas intended his rocket for spaceflight — rather, he appeared to be describing devices that probably originally derived from Chinese gunpowder rockets.

The invention of the lighter-than-air manned balloon in 1783 was a major revolution, but it was still a century and half in the future. The balloon created a revelation in mankind’s perception of the exploration of the universe because it was not accomplished by imaginary means but by the use of a man-made machine that was a device of science. This is the altered perception that was born of the Renaissance — this is the most important point to realize: that by means of a man-made instrumentality, employing well-understood physical principles, it was possible to leave the Earth. Therefore, it seemed clear to the newly enlightened mind that the problem of traveling to the other worlds that shared the universe with the Earth ought also be surmountable by means of science and mechanics. Even if the wiser heads were aware that it was unlikely that anyone would ever travel to the Moon in a balloon — hot air, hydrogen or otherwise — they were also cognizant that the idea of traveling there somehow was no longer a matter relegated to pure fantasy.

Yet, if traveling into space was simply a matter of applying the right technology, this lead to a simple and obvious question — what might that technology be? Balloons? Anti-gravity? Giant cannons? These and other ideas were all suggested. It was not until the end of the nineteenth century that anyone with an engineering or scientific background seriously proposed the use of rockets to propel a spacecraft.

We might ask about the science fiction writers. They’re seemingly always ahead of the game. Did anyone writing a science fiction story come up with the idea of using a rocket-powered spaceship before engineers and scientists did? Technically, science fiction, as a literary genre, wasn’t popular until later, in the time of Jules Verne. However, many point to the author Lucian, a Hellenic writer from Syria, who wrote A True Story in the 2nd century AD. His book included the idea of travel to other worlds, of extraterrestrial life, and, in line with the times, of interplanetary warfare. His writings, however, were largely unknown, not just to the masses but even to the elites and only a few copies were kept in old libraries and monasteries.

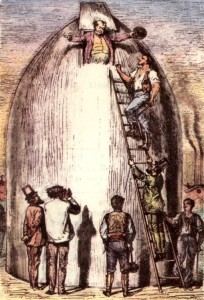

The first more modern science fiction writer who described such things is probably Cyrano de Bergerac. In his satirical fantasy, Histoire Comique: Contenant les Etats et Empire de la Lune (1657, but written 10 years earlier), de Bergerac described the flight of a manned rocket. His hero had already tried several methods of flying to the Moon, all unsuccessful. One of them employed a kind of box with wings powered by giant springs. This contraption was launched from a cliff and immediately crashed, so he wrote anyway. While consoling himself in a local bar, some jokers fasten skyrockets to the box. On the next attempt, the rockets were lit and he was launched into the sky. “The rockets at length ceased through the exhaustion of material and, while I was thinking that I should leave my head on the summit of a mountain, I felt (without my having stirred) my elevation continue; and my machine, taking leave of me, fell towards the Earth.”

Cyrano became the first human second stage in astronautical history. By virtue of some beef marrow he had rubbed over his body earlier to relieve his bruises and having reached sufficient height, Cyrano found himself continuing on to the Moon. While this novel means of travel might seem bizarre to modern readers, it was a popular superstition at that time that the Moon attracted the marrow of animals.

Although de Bergerac is often credited with the first suggestion for the use of rockets in space travel, he truly only gets half points for doing this since he only includes them in his list of possible means of locomotion. H believed that rockets sounded just as silly as all the other methods he described. One must remember that de Bergerac was trying to come up with the most unlikely-sounding methods of launching himself into space — that rockets were one of his choices was only a serendipitous accident.

On the other hand, Jules Verne took rockets seriously. He wrote of them in his classic 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon and its 1870 sequel, Around the Moon. Although he employed an enormous cannon to launch his projectile — a decision he has been much derided for by those with 20/20 hindsight — he actually chose a cannon for very good reasons. While being perfectly aware that a cannon wouldn’t work for launching people, he supplied it with rockets for steering. What makes this a real plus for Verne is that he was the first person ever to suggest that rockets would work just as well in a vacuum as in air. Even the New York Times was ignorant of that fact, when it took Robert Goddard to task for writing about Moon rockets:

“That Professor Goddard with his ‘chair’ in Clark College and the countenancing of the Smithsonian Institution, does not know the relation of action and reaction, and of the need to have something better than a vacuum against which to react—to say that would be absurd. Of course he only seems to lack the knowledge ladled out daily in high schools.”

A number of science fiction historians have pointed out that Verne was beat by a nose with the publication of Achille Eyraud’s Voyage to Venus, which came out in the same year as Verne’s novel but a few months earlier. In his story, Eyraud correctly explains that the reaction effect that propels his spacecraft is the same as that produced by the recoil of a gun and that it flies in exactly the same way that a skyrocket does. Even so, it is clear that Eyraud does not quite understand the principles involved. His rocket is propelled by ejecting a stream of pressurized water from a nozzle at the rear. This is all well and good, but when one of his characters mentions that this would require a prodigious amount of water, Eyraud goes badly astray. He has his inventor explain that the water is not lost “because the expulsion was intercepted and deviated at a certain distance by a small paddle wheel, which made the water fall into a basin from which it was forced again by the pump.” Since the ejected water is recovered in a container towed behind the spacecraft, this would negate any reactive effect and the spaceship would simply stand still.

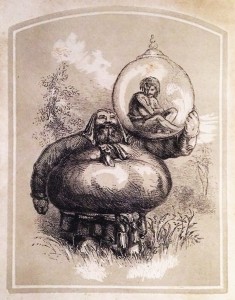

It would appear, finally, that the honor of describing the first unambiguous rocket-propelled spaceship goes to American author, Elbert Perce. In his obscure 1857 novel, Gulliver Joi, he describes a journey to a hitherto-unknown planet, “Kailoo”. The spacecraft is a hollow cylinder made of a very light substance that is nevertheless as hard as iron. It is only just large enough to contain its single passenger. The rear of the cylinder is sharply pointed. The cylinder is placed in a frame to which are attached powerful steel springs. Released by a trigger, these would give the projectile its initial velocity. In the pointed end of the spacecraft is placed a strong, square steel box. This contains a newly invented powder. From one end of the box extends a small, very strong tube. When the box is heated by the “malleable flame,” a kind of perpetually burning globular mass resembling molten iron, the powder inside ignites. “As long as a steady heat can be obtained enough to keep it in fusion, so long a steady blast of exceedingly powerful flame will issue from the tube of the steel box, which tube… extends through the aperture at the pointed end of the cylinder.” The exhaust can be controlled by a stop-cock.

Elbert Perce’s spaceship is controlled by a kind of magnetic compass that automatically keeps it pointed toward the planet Kailoo. The passenger is also equipped with a powerful telescope. The “cabin” is just large enough to allow its passenger to lie down within it. It is cushioned with a lining of fur with the controls conveniently within reach.

At the time for takeoff, the inventor inserts the malleable flame and “instantly a stream of fire issued from it, striking the rock with great violence…. The old man then pulled the small trigger that confined the steel springs, and propelled by their force, and that of the flame, I shot up into the air, the long broad flame of fire streaming behind me like the blaze of a comet.”

Once the rocketeer found himself approaching Kailoo he “shut off the supply of flame that propelled” him and descended to the surface.

If all that isn’t a perfect description of a rocketship, I don’t know what is. Our hat is off to Elbert Perce, the man who invented the rocketship.

One More Thing

If you should like to read the description of the rocketship in the original book by Elbert Perce, it is available for free reading online at Archive.org. The direct link to Chapter II is here:

https://archive.org/stream/gulliverjoihisth00perc#page/26/mode/2up

If you read to the end, you will find that despite having invented the modern rocketship, the author Perce doesn’t ultimately trust it to make regular voyages. Rather, he suggests that you will hear more of Kailoo in a newspaper that will be delivered by a large balloon traveling between the worlds, “twice a week, regularly,” he states with some flair. So much for rocketry — but then again, we still don’t have a reusable rocket that can go even into orbit “twice a week, regularly”. Perhaps Perce’s vision was accurate in more ways than one.

Great story. Rocketry has opened the door to outer space. It will lead to the discovery of new worlds and civilization never before imagined.