Published on June 18, 2012

On this date in aviation history, Max Immelmann, the German ace whose reputation had spawned the “Fokker Scourge,” was killed in France. Before his death, Immelmann was officially credited with shooting down 15 aircraft (and non-official records are conclusive that he brought down at least 17 enemy airplanes). Yet his lasting legacy was not that he had become an ace, but rather for a maneuver that was named in his honor — the Immelmann Turn.

At the beginning of the Great War (later known as World War I), airplanes were still in their infancy. By 1915, however, they had improved considerably and had become deadly tools of war. No longer were amateur pilots flying alongside one another and shooting pistols or rifles at one another. The once unarmed, lumbering observation planes that could barely carry the weight of a pilot were now mounted with multiple machine guns in the hands of a second crew member and flew at nearly 100 mph. Likewise, the first generation of the true fighter plane had a forward facing guns that shot through the propeller arc with the aid of an interrupter gear. The pilot aimed the entire airplane at the enemy and pulled the trigger — it was a deadly innovation. The sky was painted red with blood.

Heroes of the Air

Amidst the senseless slaughter of the ground war, both sides needed a personalized story of heroism and chivalry to retain public support. On the German side, Max Immelmann rose to become the first celebrity fighter pilot, a “knight of the air” who hunted the enemy with his airplane (a metaphor for the knight’s warhorse of old). Immelmann, with his fellow German fighter pilots at the dawn of 1915, were equipped with the new Fokker Eindecker — an aircraft that outclassed anything the British or French had in the air. It wasn’t long before German newspapers dubbed him “Der Adler von Lille” (the Eagle of Lille) for his exploits and many victories.

Like the others in his squadron, Immelmann was developing nascent air combat techniques based on personal experiences day by day. Pilots soon learned that approaching from above and behind meant that the enemy observer could fire back — so they tried new tactics, flying out of the sun, attacking from underneath or diving from above with great speed. New ways of fighting were developed — if the attacker approached from the side, pilots were taught to turn into the enemy; if a plane was closing from behind, “on your tail”, you went into a tight turn or pointed the nose down and dove away, perhaps dodging back and forth; and so forth. New tactics also emerged for hunting together as a squadron.

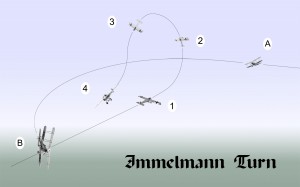

In this time of rapid advancement, Immelmann’s innovation was simple. It was a high angle reversal that allowed him to make two passes at his opponent in quick succession. Immelmann appears to be the first to grasp that air combat required maneuver in all three dimensions — climbing, diving and turning simultaneously for advantage. While most aviators today are taught that the “Immelmann Turn” is a half loop with a roll at the top, historically, this probably wasn’t anything that Immelmann ever tried. His Fokker Eindecker didn’t have ailerons, rather it used wing warping and thus a half loop with a roll at the top would have been unlikely, difficult and even risky.

The Immelmann Turn Examined

So just what was Immelmann’s high angle reversal? The best guess from reports of RAF pilots who survived is that Immelmann would make an initial pass at the enemy aircraft from the side, shooting as he closed the distance. Typically, the RAF or French pilot would then start a turn toward him or would attempt to dive away. Immelmann would pitch his Eindecker’s nose up at a high angle, causing the speed bled off. Then he would kick over the rudder and the plane would drop around into an extreme form of a tight turning “chandelle” that placed him above and behind his opponent in a position to fire again within scant seconds of his first attack. Although some debate whether Immelmann actually used the maneuver, eyewitnesses in the RAF reported it enough times that the case is fairly strong that what is described here is what he did. Sadly, confirmation is elusive since Immelmann himself never documented the maneuver in any way.

On June 18, 1916, Max Immelmann died in his beloved Fokker Eindecker over Sallaumines in northern France. His aircraft plummeted vertically into the ground, shedding its wings and tail as it went down. Whether he was shot down, as the British Royal Air Force contended, or perished when a malfunctioning machine gun shot off his own propeller, as the Germans claimed, may never be known. In an era before the invention of the parachute, Immelmann had no chance of survival. His body was recovered and buried with honors. The Fokker Scourge had come to an end, though perhaps more fittingly not due to the death of a single enemy pilot, but by the advent of a new generation of British and French fighters that could match the performance of the Fokkers in the air. In any case, Immelmann’s legacy lives on. Every generation of fighter pilots since has faced new challenges — yet the one thing that has never changed is the personal spirit of innovation and skill as a hunter — like Immelmann, today’s fighter pilots are still knights of the air.

One More Bit of Aviation Trivia

Like many of the other German aces of World War I, Max Immelmann flew with the pioneering fighter pilot strategist Oswald Boelcke. Whereas Immelmann developed personal tactics for his own aircraft, Boelcke concentrated on how to coordinate flights of multiple aircraft in attack and defense. As a result, Boelcke ultimately became the most influential tactician in the ways of air combat. The greatest ace of World War I, Manfred von Richthofen, known as the “Red Baron,” was one of Boelcke’s proteges. Even today, the “Dicta Boelcke,” a code of fighting principles, is still studied by fighter pilots. The lesson is clear — while individual greatness is exemplary, to truly make a difference requires an organization that trains and fights together.