Published on July 11, 2012

Exactly 50 years ago today in aviation (and aerospace) history the world’s first broadcast of a satellite-relayed television signal, from the Telstar I, took place. What today is so commonplace that people think almost nothing of it was a major innovation at the time. In 1962, the United States and Russia had only just started their space programs, rocket technologies were unreliable and the science of satellite communications was in its infancy. Despite that, the Telstar I satellite was a revolution. It tested and proved the capabilities of satellites for communications and, in the end, also showed the limitations and harsh realities of not just science but also the lesson that politics do not bend.

And along the way, Telstar I would also make baseball history.

Designing and Building Telstar I

The Telstar I satellite was the product of Bell Telephone Laboratories, developed under a multinational agreement that tied together Bell Telephone Laboratories, AT&T, the British and French post offices in a private venture that teamed with NASA for access to launch facilities and rockets. With each launch, NASA was reimbursed a flat fee to cover the costs, whether successful or not. This model of public-private partnership would establish the accepted way of doing business in space, which remains essentially unaltered until today — though new companies are now seeking to open satellite launch services as commercial ventures.

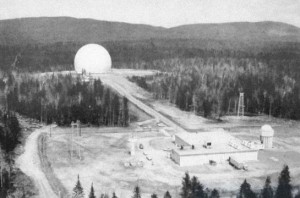

Telstar I was designed, built and tested within Bell Labs under the leadership of three notable scientists — John Robinson Pierce, the overall creator of the project; Rudy Kompfner, inventor of the traveling wave tube transponder that was used on Telstar I and II; and James M. Early, designer of the satellite’s solar panels and its transistors. The satellite was mounted atop a Thor-Delta rocket and launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, on July 10, 1962. As soon as the satellite hit orbit, it relayed its first television picture signals, showing an American flag flying outside of the satellite uplink station at Bell Labs’ Andover Earth Station. The Andover Earth Station was located in Andover, Maine, and the signal was to be received at Pleumeur-Bodou, in the Côtes-d’Armor department of Brittany on the northwest corner of France (i.e., about 250 km west of the Normandy beaches and 100 km northeast of Brest, France). It was a first successful test of many that would follow.

These first broadcasts were very low power signals and required a huge receiver antenna to capture back on Earth. The system allowed a television program to be beamed from a ground station up to the satellite and then this was rebroadcast back to a European ground station receiver antenna. The satellite would carry television signals, phone calls and faxes between the USA, Britain and France. Despite the promise of the design, there were serious limitations inherent in the technology of the day. Notably, the orbit of the Telstar I was not geosynchronous, unlike today’s communications satellites, and thus, was only connected the US and Europe for 20 minutes every orbit, which took place ever 2 hours and 37 minutes. In technical terms, the satellite’s orbit was highly elliptical, inclined at a 45 degree angle to the equator with perigee (lowest orbital altitude) of 952 km and apogee (highest orbital altitude) of 5933 km above the Earth.

The First Public Broadcast

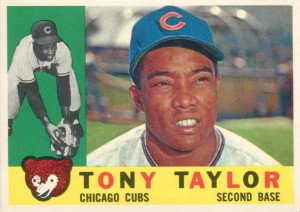

Two weeks after launch, Telstar I was ready for its first public broadcast. After its series of successful tests, on July 23 at 3:00 p.m. EDT, Telstar I relayed its first public transmission. The first images broadcast to the public were supposed to be of President Kennedy addressing Europe, but somehow at the appointed time, the White House was running late. Lacking other content in the first few moments of live broadcast, the controllers beamed an unexpected signal to Europe instead — a television signal from an ongoing game of American baseball.

As Europe watched, rather than the face of the President of the United States, instead they were treated to the television picture of second-baseman and right-handed batter Tony Taylor of the Philadelphia Phillies stepping up to the plate in a game against the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field. The pitcher for the Cubs, Cal Koonce, fired one over the plate, which Taylor hit squarely into right field. The Cubs’ right-fielder, George Altman, made the play with a smooth catch, putting Taylor out. And at that moment, the President of the United States came on television to address Europe. His speech would cover US-European exchange rates and the value of the dollar. It seems in retrospect that Europe would have probably rather liked to see the rest of the game.

The End of Telstar I

The Telstar satellite was designed for operations over many months but was instead knocked out early on by the after effects of a combination of Russian and American nuclear tests. The atmospheric nuclear weapons testing programs of both countries had excited the Van Allen Belt and this, in turn, zapped the delicate circuitry on the satellite, putting it out of action. Bell Labs was able to recover some operations for a time, but then additional damage was done and the satellite would “go dead.” Amazingly, as of 2012, both the Telstar I satellite and its slightly larger twin, the Telstar II, still remain in orbit — just another piece of the tens of thousands of bits of space junk that are tracked as hazards to space travel and, in their own little way, serve as orbiting monuments to early space science.

As for who won the baseball game, I don’t know the answer to that. I wonder, however, given the record of the Cubs….

And one other thing — doesn’t the Telstar I look strangely reminiscent of the Death Star from Star Wars?

One More Bit of Aviation History

Over the years, a huge amount of orbital debris (space junk) has accumulated in orbit around the Earth, becoming a serious issue for satellite operations. The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) maintains a database of known debris and debris fields for use in planning launches and orbital paths. Everything from the dust left behind from rocket burns, to old, dead satellites are continuously tracked. What seems like an insignificant object, such as a paint fleck that chipped off an errant Soviet satellite forty years ago, becomes a dangerous missile at orbital speeds that can easily exceed 30,000 mph. NASA estimates that as of 2011, there are approximately 22,000 objects being tracked. The oldest object of all, interestingly enough, is NASA’s own early satellite — the Vanguard 1, which was launched in 1958 and in many ways helped signal the USA’s entrance into the space race.

If you have a telescope and would like to spot any satellites flying overhead tonight, check out: www.heavens-above.com!