Published on August 26, 2012

Mehran Karimi Nasseri’s airline oddyssey began on this date in 1988. A refugee of the Shah’s pre-revolution Iran, his papers from the UN’s High Commissioner for Refugees in Brussels authorized him to live anywhere in Europe. He decided to reside in the UK, yet he would never make it there. His problems began on the way to Charles De Gaulle Airport in Paris when some thieves stole the briefcase containing his documentation. He boarded his flight anyway, hoping the matter would be worked out on arrival in London. Instead, the British refused him entry and he was sent back to Charles De Gaulle airport. Yet there too the French authorities denied him entry to France. A call to the UNHCR office in Brussels uncovered that they could only issue him papers if he showed up in person in Belgium. But as Mehran was stuck in Terminal 1 at CDG, he could not make it to Brussels without breaking the law — which he refused to do. Mehran decided to stay put while the authorities worked it out. Thus began the longest layover in history — it would last 17 years.

Early Attempts to Resolve the Situation

Mehran Nasseri’s convoluted story of bureacracy run amok began not at Charles De Gaulle’s Terminal 1 but in Iran under the Shah. Like many Iranians, he had protested the Shah’s rule. Persecuted, he fled the country in 1977 and sought refugee status in Europe. After numerous filings and denials, he was finally approved and issued formal refugee status by the UNHCR in Brussels, Belgium. Yet once he was stuck in Terminal 1, he lacked paperwork to prove those rights. Figuring that he could camp out for a few days at CDG’s Terminal 1 while the authorities sorted it out, he decided to stay put. Surely, he thought, they didn’t want him in the terminal any more than he wanted to be there.

However, the French system didn’t work that way. Briefly arrested, the court system didn’t agree with the police. They ruled that Mehran had broken no laws and could not be held. Moreover, they ruled that he had the right to stay in Terminal 1, though they also noted that the courts could not force the immigration authorities to allow him entry into France. Everyone looked to Brussels and the UNHCR to sort it out. Yet everywhere it seemed that the government authorities dragged their feet. He was caught in a bureaucratic corner from which it seemed no easy paperwork solution could free him. As the weeks passed and became months, then the months passed and became years, Mehran Nasseri simply waited — eventually, he reasoned, he would be flown to the UK where he could take up his residency legally. Meanwhile, he worked out the basics of survival within the confines of Terminal 1.

Surviving Terminal 1

Mehran’s challenges were many, but one by one he sorted them out. Lacking money, he soon found that many of the employees at Terminal 1 were understanding and would give him enough to get by — he steadfastly refused to beg and depending instead on vouchers. There were many airport toilets to use when needed. He had water available too. For food, he could eat in the airport restaurants, so long as he didn’t mind the repetitive nature of food served. As it happened, he developed a fondness for the terminal’s french fries. To wash up, he found that he could use the airport washrooms at night and in the mornings before the rush of early flights. Weekly, he could do his laundry in the bathroom sinks. He could find unused toothpaste and toothbrushes in airline travel kits left behind by travelers. He also worked out how to sleep on the terminal’s rather uncomfortable seats. Finally, he befriended many of the employees and shop owners in the airport. It seemed he could outlast the bureaucracy — and sooner or later, it was likely that something would come through.

At that point, the situation could have been easily resolved. Perhaps the Belgians or the French could have allowed him some special legal authority or dispensation. Perhaps a trip could have been made from Belgium to hand deliver the documents to him since he couldn’t travel to Brussels. Perhaps he could be given temporary passage through France to Belgium. Indeed, any number of things could have been done to resolve the situation — but instead, it seemed more and more apparent that the bureaucracy simply didn’t care, or worse had no authority to act. A bizarre situation emerged where as long as Mehran was willing to wait, the bureaucracy was willing to forget about him and the problems he presented — it was less work that way too, making it a compelling solution for the government employees involved.

The Legal Situation Worsens

Mehran’s plight was newsworthy and after awhile, his case became an international human rights issue. After four years living in Terminal 1, in 1992 his case was reviewed by the courts in France as a matter of human rights. Mehran was represented by a French human rights attorney, Christian Bourget. Yet even then, things only got worse. Instead of resolving the situation, the French courts ruled that since Mehran had been accepted by the authorities into Terminal 1, he had the legal authority to stay as long as he wished. However, they also noted that without paperwork, he could not exit the terminal, nor travel to another country. Finally, they noted that while France had the authority to repatriate him to his home country, Iran was no longer his home country. He was stateless — but at least they recognized his basic refugee status. Thus, rather than resolving the situation, the red tape only tightened its hold on him.

Above all, Mehran had done nothing wrong at all; he had broken no laws. He was a gentle man, a man who broke no laws and harmed none. In fact, he had applied for his refugee status properly, had been approved properly and had been issued proper documentation for his status. It was the authorities who were essentially imprisoning him in Terminal 1. The matter was just a question of paperwork — and yet now the years were ticking by as Mehran lived in bureaucratic limbo. Psychologically, the long stay had taken its toll. He had become fragile as a result of the ordeal. He no longer felt confident enough to go outside. He no longer felt he had a place in the world.

And then, Belgium took further action on his case — but yet again, it only made things worse. In accordance with the law, the authorities in Brussels ruled, Mehran no longer had the right to visit Belgium. As an approved refugee, if Mehran voluntarily left from a country that had accepted him (in this case, Belgium), he could not legally return there. Thus, as crazy as it sounded, Mehran was denied the right to even return to Brussels in person to get additional copies of his approved paperwork. The maze of red tape had now become a veritable prison.

Another Human Rights Challenge

By 1995, Brussels finally reversed itself. The authorities offered that Mehran could live in Belgium, but only if under the continuous care of a social worker. Apparently, they felt that Mehran must be crazy to have stayed in Terminal 1 for so long. Mehran, who had taken to studying economics and reading books to expand his education and to pass his time, could not bring himself to leave the terminal building voluntarily. Moreover, he rejected any declaration that he was less than competent. Also, he pointed out that he had no desire to live in Belgium — only the UK. He stayed, even when the door was opened.

With the passage of a full decade, Mehran had finally settled into a reasonable life in Terminal 1. He had adjusted to the routine and, despite the earlier challenges, had actually come to like his life there. The food was good, even if he rarely had quite enough. He could move around with his belongings (still packed in his luggage) as he chose. He was a fixture at the airport. While some kept their distance, others supported him and were always willing to lend a hand or give him a cheerful wave.

Those who made announcements over the public address system and manned the information desks had come to accept his presence. Those who worked in the restaurants helped him. He received and sent mail from his address at the airport. Visitors made trips to see him. A priest would visit weekly. Others would stop by for coffee and discussion. And he was a voracious reader, working his way through every bestseller available in the airport bookstores.

Mehran Finally Enters France

After so many years, Mehran was essentially living the life of a homeless man on the streets — except that his street was the airport. He looked and lived like the homeless, dragging his things around with him. He had even made claim to a certain red chair — his spot in the airport. He had even created a semi-permanent living area in the corner of Terminal 1, ringed with his boxes and luggage, all his worldly belongings neatly organized for his daily routine. He didn’t work and he got by from day to day. The highpoint of this period was that in 2003, Steven Spielberg purchased the rights to his story — reportedly for $250,000, plus some rights to a percentage of ongoing profits. Mehran’s salvaged luggage soon carried signs advertising the 2004 movie, “The Terminal” which was loosely based on his life at Terminal 1. Even then, he lived as before — in a fragile psychological state, depending on found free meal vouchers and passing his days reading every book in the bookstore.

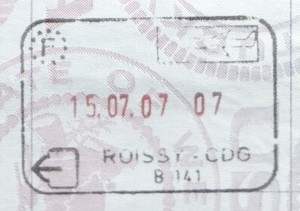

It all came to an end finally after 17 years. In July 2006, Mehran had a health crisis — he was in his 60s and had lived at the airport relatively free of health problems. Facing a medical crisis, the French health care system discovered it had the right to take him to the hospital for treatment — in France. He was removed from the airport and, while at the hospital recovering — a period lasting approximately six months — his living space in Terminal 1 was dismantled. Once healthy enough to be released, he was not returned to the airport, but rather put into a Parisian shelter near the XXth arrondissement. From then on, he would have to live in France, off of the airport grounds. After it was all over, when asked, Mehran looked back on his time at Terminal 1 with fondness — that was his home and his life and he only wished to return there again. Quite likely, he is a wealthy man based on his movie profits, yet even then he chose to live in a shelter. He was, in the end, a man without a family, a country or a place in this world — except for the halls of CDG’s Terminal 1.

Danielle Yzerman, the press spokeswoman for Charles De Gaulle Airport, summed it up perfectly, “An airport is kind of a place between heaven and earth. He has found a home here.”