Published on September 27, 2012

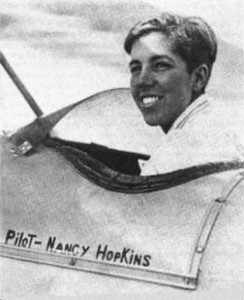

“Ever since I was in high school, I had just one determination — to fly. I don’t know why either.” So said Nancy Hopkins, a 22 year old woman from the Washington, DC, area who, after learning to fly at Hoover Field in Arlington, Virginia, moved to Long Island. Hearing about the Ford National Reliability Air Tour, she decided to enter — one of 19 pilots who did that year. It all worked out perfectly too — well almost, at least until she was just 40 miles from Memphis, Tennessee, during one of the final legs of the trip. Without warning, she suffered a catastrophic engine failure….

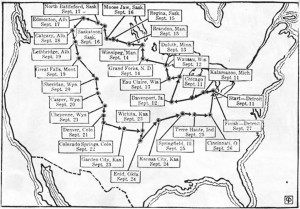

When the gaggle of 19 planes took off on September 11, 1930, the course ahead involved 5,200 miles of flying on a strict schedule. There were stops laid out in 30 cities and towns that spanned the US and Canada combined. Each coincided with press events, lunches, dinners and special receptions that had been set up for them. That was a requirement of the Ford National Reliability Air Tour, that no matter what the weather, no matter what happened to their planes, to the very best of their ability the pilots were to hold to the itinerary. Points would be awarded for each leg of the trip — with the fastest finisher placing highest.

It was a lot to ask of their aircraft and, given the weather, nobody knew for sure if the schedule would be upheld. The course started and ended at Ford Airport in Dearborn, Michigan, and with good reason as this was the Ford National Reliability Air Tour. This was a race more about proving that air travel was safe and sensible more than about raw speed and pushing the limits of aerodynamics. The Ford Motor Company had ventured into aircraft design and just a few years earlier, had launched its first airliner — the Ford Trimotor. Now, the Fords were the top seeded entries. As for Nancy Hopkins, she was in a small, light blue colored, single engine aircraft. It was one of the slowest planes of the field.

The Route

If all went well, the aircraft would arrive together on September 27, 1930 — today in aviation history! Starting from Dearborn, the aircraft would fly to Kalamazoo, Michigan (yes, there really is a Kalamazoo) where they would eat lunch. Afterward, they would fly on to Chicago, Illinois, for dinner and an overnight stay. The following morning, after a good breakfast, the aircraft would depart for Davenport, Iowa, have another lunch with another group that was eagerly awaiting the flyers’ arrival, and then they would continue to Wausau, Wisconsin, for another celebratory dinner. After another overnight, they would have another breakfast meeting before flying on to Eau Claire, Wisconsin, where they would enjoy another luncheon before proceeding onward to Duluth, Minnesota, for yet another dinner reception and overnight.

The trip continued on from city to city in this way with dinners, luncheons, breakfast events, meetings and great fanfare at each of the thirty stops. It was a wonder that the entire bevy of pilots didn’t put on an added 20 pounds by the time the Air Tour ended! The course was a huge loop that went as far northwest as Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, and Edmonton, Alberta, up in the far Canadian north, and then turned to head south as far as Enid, Oklahoma, having traced the mountain range of the Sierras. From there, they would continue through southern Illinois, Indiana and Ohio (somehow skipping Dayton and the site where it all began with the Wright Brothers Bicycle Shop), before turning north to Dearborn to finish at the same location where it had all started.

The Air Tour proved just how far aircraft technologies had come over the last 20 years since Cal Rodgers had made his daring flight with the Vin Fiz across the nation, crashing at least 17 times along the way. With the Vin Fiz, when Rodgers arrived in California, the only original part remaining from the plane that departed the east coast was one of the landing gear skids. The rest had broken and been replaced along the way. To accomplish even that, a special train had steamed along the rails the entire route accompanying Cal Rodgers with a maintenance team and mobile aircraft construction workshop, spare parts, wood and fabric in tow. It had been a huge venture and very costly.

Yet by the 1930 Air Tour, no maintenance trains were fitted, no special teams deployed and no sleeping cars for the exhausted pilot after each hop of 20 to 30 miles (as Cal Rodgers had done). The average flight in the Ford National Reliability Air Tour was just about 175 miles — thus, the participants would fly two flights of about 2 hours a day each. At each stop, the pilots would do their own maintenance or hire local mechanics to do the work. Over 5,200 miles in total distance, it was the equivalent of flying the Vin Fiz’s historic flight two and half times in just 17 days.

The Participants

As it happened, of all 19 planes that departed Detroit, virtually every one of them arrived safely in Detroit on September 27. It was an extraordinary thing — though the weather had cooperated fairly well in retrospect. Among the top aircraft participating were Jim Ray’s Pitcairn PCA-2 autogyro and a pair of Ford Trimotors. Bellancas, Wacos, and many other types filled out the starting list. Among the entrants were the youngest aviator, Eddie August Schneider (he would go on to win his class and place 8th overall), and such famous names as Walter Beech, who two years later would found with the Beech Aircraft Company, as well as John Livingstone, the famous air race pilot (he would place second overall in his Waco CRG — and would go on to win a total of 80 first place finishes at national air races around the United States, a record which will likely stand for all time).

Hopkins and her Emergency Landing

When Nancy Hopkins’ little Viking Kitty Hawk plane (NC30V), was nearing Memphis, she was flying at 4,000 feet, enjoying the good weather and looking forward to another dinner. Suddenly, without warning, her 90 hp Kinner B5 engine made a hard sound and instantly cut out. The prop windmilled to a stop, leaving one blade sticking up in view ahead of the cockpit, mute testimony to the problem. Where before, she had been serenaded by the sound of her big radial engine, now there was only the sound of the wind whistling between the wires and over her little biplane’s wings. She glided down in a wide circle searching for a reasonable landing spot. She spotted a field and lined up so that she would come to a stop near a small farmer’s shack at the end.

The touchdown was fine but as the plane bounced toward the shack, she suddenly realized that all around it were small stumps. The farmer had recently cleared a small stand of trees from around his little home, making the routine, if emergency landing something of an unexpected challenge. She turned and missed most of the stumps, but put a wheel into an irrigation ditch, and blew a tire before coming to a rest. She was uninjured and somehow had avoided flipping the plane. The other contestants would continue on without her.

Once on the ground, Nancy Hopkins went to work on the plane — she started going over the engine looking for some damage or problem. As she put it, “…the main thing was to see what was wrong. I pulled the propeller, checked out the cylinders, found the problem, went to work with a screwdriver and some wire, and it started right up. All I could think about was the great shop course back in Central High, and how glad I was to take it.”

After taking off, she caught up with the rest of the field for dinner. Sadly, she had lost enough time to put her out of the top 8 finishers. She finished 14th in the field. It was an excellent result considering the problem, the emergency landing, the stumps, the irrigation ditch and her own repairs. She had done quite well considering that she was alone in the plane and there were (obviously) no mechanics around! In the end, she received $200 in prize money for having completed the Air Tour. It wasn’t bad — the top finisher received the princely sum of $2,500 (which equates to $32,800 in today’s money, adjusted for inflation).

Nancy Hopkins Quits Competitive Flying

Nancy Hopkins “mostly” retired from competitive flying a year later when she married Irving Tier and dedicated herself to raising a family — yet even then she still competed sometimes, taking the speed prize for Connecticut in 1931, entering the Meridien Aviation Pylon Race in 1932 and even competing in 1971 in the New England Air Race! Quite obviously, she wasn’t done with aviation quite yet after the Air Tour. Anyway, she chose the right sort of husband since he owned a fleet of his own airplanes up in Connecticut….

The top finishers at the 1930 Ford National Reliability Air Tour were as follows:

1. Harry L. Russell

2. John H. Livingston

3. Arthur J. Davis

4. Myron E. Zeller

5. George W. Haldeman

6. Walter H. Beech

7. J. Wesley Smith

8. Eddie August Schneider

One More Bit of Aviation History

In 1931, the recently married Nancy (Hopkins) Tier quite nearly died in a plane crash. At 1,000 feet of altitude her Viking Kitty Hawk stalled and entered into a flat spin. She could not recover since the airflow over the tail was blanketed by the wing. She was dangerously low and, as she was wearing a parachute, she elected to bail out. Once she had climbed out of the cockpit onto the wing, something about the unbalance or asymmetrical drag she created, caused the plane to stop spinning. Quickly, she climbed back into the cockpit and pulled back on the stick to recover from the dive. She pulled out just 200 feet over the ground. It was a very close call. After the story made the New York Times, the Viking aircraft company offered her a job as their spokeswoman.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

How well did the two Ford Trimotors do in the race that year?