Published on September 28, 2012

Jaromir Wagner was a born stuntman, if an amateur one. Born in Czechoslovakia and having escaped from behind the Iron Curtain to West Germany in the 1950s, he set himself to practicing his new-found freedoms in unique ways. As Jaromir put it, “I left the Czech nation and found that I could freely travel around the world and realize my dreams. For those of us who escaped, this was new because before nobody would allow such freedom.” It probably surprised his friends that one of his dreams was to strap on a pair of roller skates, take hold of a rope tied to a car, and see how fast he could go on the autobahn. “Oncoming drivers looked at us as if we were fools. It was a miracle to me that nothing happened to us. The cops just caught us and I lost my license, even though I was the one on skates!”

From his first attempts — attaining 92 km/h — he steadily improved his art. Over time, he established a record speed that still stands today of 270 km/h, though in better controlled conditions than on the autobahn, using prepared surfaces with special tow gear that he invented over the years of pushing the limits. Having set a pretty high mark of achievement (and concurrently setting down a speed skiing mark of 180 km/h), he set himself to his next venture, flying across the Atlantic Ocean as a wing walker. On this date in aviation history, on September 28, 1980, Jaromir Wagner, a 41 year old auto dealer, started his journey. It would be an eleven day adventure that proved more difficult and challenging than even he could have imagined.

Preparations

For three years, Jaromir prepared for his mission. Despite attempts at finding a sponsor, very few he spoke with understood his dream or were willing to back it. “I prepared for a few years, I did all kinds of sports, I was fit and ready. I trained extensively and finally I was ready. I had to go ahead anyway because I had too much debt since potential sponsors did not get it, they couldn’t understand my dream — but it was worth it.”

To get used to the wind force and balance, he took to riding atop a moving car, developing a harness and bracing system into which he could tie himself. Wind chill proved a serious issue and, given the northern latitudes of the route he would need to take, it was a matter of some experimentation. He planned to hop from Giessen, in West Germany, to Scotland, then to Iceland, Greenland and Newfoundland before heading south to New York City. The northern passage across the Atlantic would involve serious challenges to ward off frostbite.

For his aircraft, it was clear that a light, twin-engine aircraft would be best suited. This would be no high altitude operation, since the higher one goes the colder it gets. He would not have oxygen systems either and, to put it bluntly, a light plane is more affordable than a jet anyway. He made arrangements for a twin-engine Britten-Norman Islander with two pilots to fly him across. They estimated that the flight would require at least 40 hours in the air.

For clothing, he tested a three layer outfit of different materials, borrowing from SCUBA for the final insulating layer, with a layer of insulating cloth between and at the outside, to prevent windchill, a full body leather riding suit. Goggles and a helmet perfected the outfit. Flying to America, his entire outfit was in bright red, white and blue.

The Flight

Taking off on September 28, 1980, his first hops went perfectly. He flew from Giessen to Scotland, but then, in the late September weather, found that he could not proceed. As storms and winds buffeted the North Atlantic route, he waited. Finally, the weather broke and he was off. At Iceland, he was tired but ready to continue after an overnight. The hop to Greenland, however, proved far more difficult as temperatures plummeted to -13 degrees Fahrenheit. After landing, he considered canceling the last over water leg to Newfoundland, but decided that if he could endure it once, he could do it again. The following day he made Newfoundland without problem, though again the extreme cold that buffeted him took its toll.

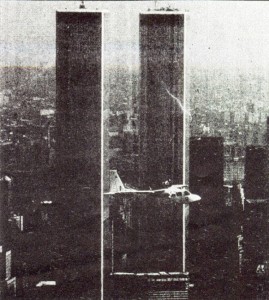

Before departing from Canada, he noted that “I’m doing it because I like it; I like the risk and it’s a thrill.” Yet he also added regarding the hard job of flying atop the Islander, “The time gets longer every day.” He departed and flew to Vermont. Bone-tired, he rested before the final short hop to New York City. As a grand gesture, on arrival, he orbited the Statue of Liberty after flying down the Hudson River at low altitude. A gaggle of press helicopters followed him closely, jockeying for position to report on the spectacle. There was a tight moment when the entire airborne fleet had to dodge around the Goodyear Blimp before heading to New Jersey for his final landing.

After touchdown, Jaromir was ecstatic even if hunched over and exhausted. His body beaten by the wind. The adventure had required 43 hours of flight, all of it with him exposed to the elements on top of the wing. He hoped that the press coverage would get him funding to fly to California, but none resulted. With a smile, he could just think ahead of his next venture — “Maybe I will go around the world next time,” he said, however, he added, “right now it’s too cold.”

Aftermath

Incredibly, it would not be a stunt accident that would finally end Jaromir’s stunts, but rather a car accident while traveling in Brunei. As he put it, “After that, I reviewed everything in my life. I realized that maybe I could die after all if I continued — that was the likely end of it — and so I calmed down.”

Now in his 70s and retired after a career in the auto industry, Jaromir looks back on his achievements with pride. He hopes that others will someday beat his record. He may not have to wait long as another Czech, David Bryknar, has taken up the rope and strapped wheels upon his feet — as for Bryknar, he says that Jaromir Wagner’s story is his own inspiration. Will Bryknar go on to fly around the world atop a wing? Only time will tell.

See David Bryknar’s website: http://www.bryknar.cz/ (in Czech).

One More Bit of Aviation History

One of the two pilots who flew Jaromir Wagner’s Britten-Norman Islander was a man named Robert J. Moriarty. Years later, when delivering a v-tailed Beechcraft Bonanza, while passing through Paris, he got the idea of flying under the lower span of the Eiffel Tower. To document the effort, he brought along a cameraman. On March 31, 1984, he climbed into the airplane at Le Bourget Airport and took off. Circling Paris, he lined up, flew down the gardens that lead to the Eiffel Tower and passed neatly underneath. Although full press photographers were contracted to document the flight, the French Government refused to allow the event to be published for over a month, by which time it had lost its importance and newsworthiness.

Today’s Aviation History Question

What is the highest flight a wingwalker has ever accomplished?

Jaromir Wagner Mira… where are you now?

Jaromir, do you remember that you were preparing for your flight to America in 1979? I was the soldier who was coming to your house for you to work on my Audi RO 80. You were flying down the Autobahn near Giessen. I was in college at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia. So sorry I couldn’t get up to Fairfield, NJ. I wish you well. Dennis