Published on October 13, 2012

By Thomas Van Hare

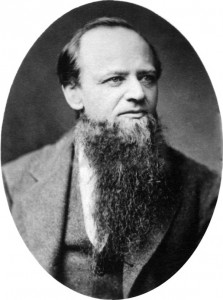

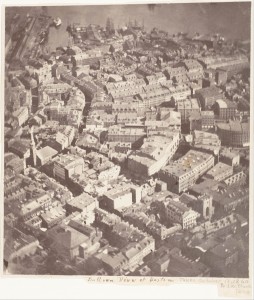

As the balloon, “Queen of the Air”, drifted lazily over Boston at 1,200 feet of altitude, James Wallace Black pointed his Daguerreotype camera toward the harbor. He carefully opened the aperture and exposed the first glass negative to the light of the city below. Then, closing the aperture, he climbed under a hood to block out all outside light and carefully removed the glass plate from the camera. Then he replaced it with a second plate. Reemerging from the darkness of the hood, he adjusted his camera’s position and again opened the aperture, timing off the seconds until he could close the aperture, return under the hood and remove the plate, to replace it with yet another. He repeated the process eight times that day, on October 13, 1860 — today in aviation history — and in so doing become the first person in the world to successfully photograph a city from the air.

Eight Plates but Seven Failures

James Black’s aerial photography mission was a venture shared with a famous balloon pilot, Samuel Archer King, who had helped pioneer aerial photography. In July 1855, in one of his first ascents in a balloon, “Buffalo”, Samuel King had brought along a photographer. Together, they shot a series of photos of the ground — these may well have been the first aerial photographs in history. Three years later, Félix Nadar in France (that was his nom de photographe, his real name was Gaspard-Félix Tournachon), would similarly shoot photos of the rolling European countryside.

Earlier, King and Black had attempted to photograph Providence, Rhode Island. While the flight went perfectly, after landing they discovered that none of the photographs developed properly. They had failed completely.

Thus, they planned another balloon flight to break new ground by photographing the complexities of a city from the air. After a successful flight over Boston, King landed his balloon and James Black took the camera and plates back to his lab. He was careful not to expose or drop the storage box of the eight, heavy glass negatives. The plates were heavy and unwieldy, measuring 10 1/16″ x 7 15/16″.

At the lab, he entered his dark room and slowly developed each of the glass plates negatives, hoping that the long exposures, chemical compounds and movement of the balloon would not spoil them. This is what had happened in the earlier flight over Providence.

One after another, as he developed the plates, James Black was saddened to observe that yet again the Daguerreotype process had failed them. Often the balloon’s movement was too great for the long exposure, sometimes the chemical compounds had not exposed properly. Some the plates had been inadvertently exposed to extraneous light, and so forth. Suspended under a balloon in a small basket with a big camera had been challenging, to be sure. The challenge was completely the opposite of the carefully lit and absolutely still settings of his photography studio.

Finally, one of the glass plates proved reasonably good. There was a bit of blurring at the bottom, where the city was closest and the perspective-based lateral movement was relatively the highest, but it was well-framed, clear and perfectly exposed. James Black was overjoyed. He developed the rest of the plates, hoping for more, but discovered that none of the others were good. In the end, just one of the eight had come out. Yet he had done it — they had captured an image of the city of Boston, Massachusetts.

It was the world’s first photograph of a city from above.

Printing and Selling the Photo

James Black was no amateur when it came to photography or its business possibilities. As a professional photographer in the earliest days of Daguerreotypes, James Black had made a living by selling portraits and still life photos. The public was amazed at the magic of the camera and viewed each photograph as if it was a painting to be hung on the wall.

Therefore, Black could see the potential market for a Daguerreotype photo of Boston from above. He planned even to display the image in his studio on a screen and charge admission to see it. As well, he knew that he could sell individual prints in a smaller size. To add to the marketing value, he named his photograph (as artists also named paintings) with the descriptive and poetic phrase, “Boston, as the Eagle and the Wild Goose See It.”

He was right — his Daguerreotype was a sensation. People had never seen their city from above and, looking at the photo, they could imagine themselves up there, in the “Queen of the Air”, floating high over their city.

After his aerial photograph success, James Black continued with his successful career as a portrait cameraman, advertising in the local newspapers for business. It isn’t clear whether he ever again soared aloft on another aerial photography mission, however. Just a few years afterward, the Civil War erupted, tearing America apart into the Union in the North and the Confederacy in the South. Balloons and photography would come of age during the war, but not in James Black’s hands.

James Black also added a trick to his repertoire, the so-called “magic lantern”, which was an early equivalent to the overhead projector from schools. The “magic lantern” worked by inserting a photographic plate in the front and a lit candle within the open-topped box in a darkened room. Through a lens, in the reverse of a camera, the image that was captured onto the plate would be projected onto a large viewing screen. One can only imagine how the citizens of Boston must have reacted to the aerial photograph of Boston as he projected it on a large screen.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Aerial photography from balloons would continue to advance and finally give way to aerial photography on airplanes.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Who invented stereo photography from aircraft and how did it work?