Published on October 14, 2012

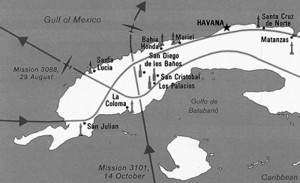

As U-2 pilot Richard S. Heyser of the 4080th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing (4080th SRW) reached 72,500 feet, he adjusted his course to pass over Cuba from the south to the northern coast of Cuba. As he turned to the north to begin his pass his plane had flown straight into the rising sun even if the first light of day was not yet illuminating the water and land below. It was partly cloudy with about 20 percent coverage. As Heyser’s U-2 flew toward Cuba, the dawn finally reached the surface below. He leaned forward to peer into the downward pointed drift sight. He wasn’t concerned about navigation and drift, rather he was watching for Soviet-built SAM-2 surface-to-air missile launches. These missiles could reach high enough to take down a U-2 reconnaissance plane.

As Castro’s Cuba passed by, he triggered the U-2’s cameras that were nestled in the aircraft’s Q-bay, including the highly classified Hycon “B” camera with its 36″ focal length and the Perkin Elmer 70mm tracking camera. Something was up in Cuba and the CIA or, since the plane had just had a USAF tail number applied so as to provide plausible denial of spying in the event it was shot down (same planes, same pilots…), the USAF was intent on finding out just what. The year was 1962 and today in aviation history marks the 50th anniversary of the events that started the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The Flight

As Heyser’s U-2 passed over Cuba, he watched intently for the telltale flash and rising flame with smoke trail of an SA-2 launch. If he saw one, the guidelines were to take evasive action. Presumably, this was done by turning toward the missile and then, as it neared, turning away sharply in hopes that the missile would pass harmlessly by. Whoever thought up those tactics clearly wasn’t considering how delicate the balancing act Heyser (and all U-2 pilots) played while flying at high altitude. A turn was a gentle thing since the plane was operating the very peak of its absolute ceiling, at the highest altitude it could go — at that altitude, only 3 knots of airspeed separated maximum speed and a stall.

Put simply, the plane flew at the very apex of where the stall speed and maximum speed converged at the top of the flight envelop. This new C model of the U-2, which had only just come into service, could reach 2,000 feet higher in altitude than the older A models, yet every flight was flown to maximum performance. At 72,500 feet, anything more than the slightest turn, unless coupled with a significant loss of altitude, would stall the wing. A recovery from a fully developed stall at this altitude would be challenging, though it could conceivably force a missile to miss. Most critically, the U-2 was essentially a lightly built, fragile aircraft. It lacked even a central pass-through wing spar so as to save weight — instead the wings were simply bolted to a fuselage shell.

Earlier, at midnight, he had taken off and flown over questionable weather in Texas. Some of the four pilots who flew later that night out of Laughlin AFB, departing so as to pass over Cuba in two hour intervals, flew into the teeth of a thunderstorm. One took off directly into the heart of a thunderhead and flew upward through lashing rain, gusty winds and nearly continuous lightning — he broke out of the top of an anvil cloud at 50,000 feet. All of the pilots held to the schedule, so critical was the photo reconnaissance to be undertaken that day in the wake of the first evidence of a possibly ominous development on the island.

No SA-2 launches were observed and Heyser slowly turned the U-2 toward Florida. As the coast of Cuba passed behind, he switched off the camera. It had captured 928 images, photographing the western end of Cuba. As he passed into US airspace southwest of Miami, he began a long descent toward a military airfield just south of Orlando, Florida, called McCoy AFB. For the first time, he broke radio silence requesting landing instructions — prior to that, the entire mission had been in complete radio silence down to the use of light signals used to give take off clearance at midnight when he had departed.

While nowadays, McCoy AFB is simply known as Orlando International Airport, back in 1962, it was a rather secretive military base in the midst of an area of Florida that was not highly populated. Nonetheless, the days of hiding the very existence of the U-2 were over — what was most important was not hiding the plane, but rather protecting its capabilities, flight schedule, routes and destinations. For this flight, Heyser had taken off at night from Edwards AFB at midnight on October 13th and flown across half of the USA before coasting out into the Gulf of Mexico and heading into the sunrise toward Cuba. Clearly, the early morning flight had taken Cuban and Soviet air defense troops by surprise. The pilots who were to come after him would undoubtedly be more closely watched.

After landing at McCoy AFB at 9:20 ET, the U-2 was taxied to its hangar and the film removed. Heyser was hustled into a classified briefing with two SAC generals (one being Major General K.K. Compton, SAC’s Director of Operations and the other Brigadier General Robert Smith, SAC Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence!). While still in his pressure suit from the flight, he debriefed the generals. Some of the film was loaded onto a T-39 for a flight to Offut AFB while the so-called “B configuration film” was raced to a waiting high speed single engine jet which took off and flew at maximum speed to the Washington, DC, area. It landed at Andrews AFB and the film canisters, still undeveloped, were hustled into a waiting car and raced downtown to a CIA and DoD funded facility called the NPIC (National Photographic Intelligence Center) for analysis at noon, arriving just three hours after Heyser’s landing in Orlando.

Photographic Analysis

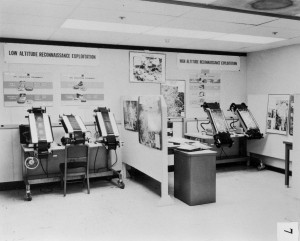

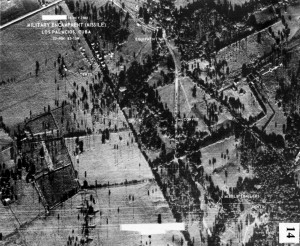

The analysis effort raced into high gear. The film was developed and split out for immediately review to a team of highly skilled photographic analysts. To ensure maximum resolution, they only looked at negatives and were used to seeing the Earth in negative — light was dark and dark was light. The morning shadows, coupled with the knowledge of the time of day that the photos had been taken gave them the ability to measure heights of objects, trees, vehicles, buildings and even people with a high degree of accuracy — simply measure the length of the shadow, compare it to the angle of the sun and you had the precise height, usually within a couple of inches. By comparing multiple frames, multiple measurements could be averaged to get greater precision.

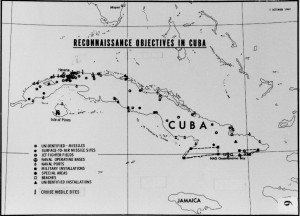

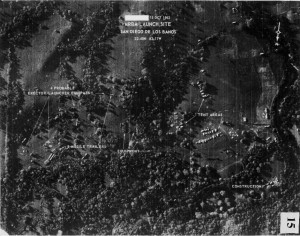

It took the analysts a single day to find what they were looking for — a Soviet-style construction site that could only mean one thing, the Cubans were preparing for the arrival of the Soviet SS-4 tactical nuclear missile. The site was at San Cristóbal in Pinar del Río Province, an area of western Cuba directly southwest of Havana (halfway between Havana and the western tip of the island). By mid-afternoon, positive photographic prints were produced and marked with labeling — the events were of such critical importance that a meeting was scheduled with the President of the United States, John F. Kennedy.

At 6:30 pm on October 15, 1962, just one day after Heyser’s flight, President Kennedy and his nine member National Security Council sat down in the White House conference room. Five others joined the meeting, all key advisers to the President. The CIA and USAF briefing began with a simple statement that evidence was clear — the Soviets were placing nuclear weapons on Cuban soil.

The Cuban Missile Crisis had begun.

One More Bit of Aviation History

The history of the Cuban Missile Crisis is well known and deeply studied, though few people are aware of the incredible deeds of the CIA, USN and USAF in performing aerial reconnaissance over Cuba. Richard Heyser would make a total of five flights over Cuba during the crisis. Ten other U-2 pilots would also fly during the crisis period. The photo reconnaissance operations were some of the most intensive in history and for the next 13 days, up to five U-2 missions were tasked daily, usually with two hour intervals during daylight hours when the sun angle was best — a little known fact of the crisis. The USN also flew high speed, low altitude flights to get high resolution imagery of specific sites that had been identified through the U-2 overflights. Many of the low level flights were met by a hail of anti-aircraft fire.

In the end, of the U-2 pilots who flew over Cuba, two would lose their lives — one, Major Rudy Anderson, was shot down by a SAM-2 on the final day of the 13 straight days of the operation over Banes, Cuba, on the northeast side of the island (two days earlier, another U-2 had been fired on from Banes, Cuba, but had escaped). The other died after the end of the crisis when his autopilot failed at high altitude and the airplane entered a flat spin. The pilot, Captain Glenn Hyde, probably attempted to bail out at 10,000 feet. The plane crashed 40 miles south of the Florida Keys — it was later taken up in a classified underwater recovery operation. The pilot’s parachute never opened and his body was never recovered though some of his survival gear was located on the waves in the immediate aftermath of the crash.

These two men were the only casualties of the Cuban Missile Crisis and U-2 missions afterward, testimony to the extraordinary risk and heroism of the U-2 and other reconnaissance pilots who flew extraordinarily dangerous missions to provide the President of the United States with the information needed to manage and resolve the crisis, thereby avoiding World War III. After the crisis ended, the USAF/CIA continued to fly two or three missions per week to monitor the Soviet draw down, though the flights would originate and recover to Barksdale AFB in Louisiana, which was opened as a new base for the U-2 flights — no other losses were suffered.

The names of the U-2 pilots involved during the crisis period were: Major Buddy L. Brown, Major Rudy Anderson, Major Richard S. Heyser, Captain Gerald McIlmoyle, Captain James Qualls, Captain Daniel Schmarr, Captain Roger Herman, Captain Ed Emerling, Captain Charles Kern, Captain Robert Primrose, and Captain George Bull.

Today’s Aviation History Question

Why weren’t the CIA’s new Corona satellites used to photograph Cuba instead of the U-2s?

The resolution was not quite good enough for a proper analysis to be performed from that satellite at that time. Also, there was too much cloud cover over Cuba in the area between the satellite and the top of the U-2’s ceiling, in fact just below the ceiling.

Randy O. Bowling, USPHS 79-80

My Dad was in the 72nd Airborne Squadron, 1st Air Commando Group, 10th AAF, CBI, during World War II

R.O.B./

I was a civil service aircraft mechanic working on F8U-1P photo reconnaissance planes that also took a “Kodak Moment” on Cuba. We worked at NAS Norfolk, VA, which also happened to be the #2 target on Moscow’s hit list. Thanks to our government, that war never happened. A prime example of “cooler heads prevailing”.

Quite proud of the role the men of the 4080th (and their commander, who later briefly commanded the SR-71 wing, before being promoted to brigadier general… my father) played in the history of not only the military and the U.S. but also the world. Most are gone now but their sacrifice, dedication and achievement will remain remembered and appreciated by many.

John —

My dad was a U-2 pilot at Laughlin and I recall us meeting, but my brain is old and slow… what year were you born?

Fred,

I was born in 1954. Just turned 8 a few weeks before the crisis.

John

My grandfather was General Robert Smith, SAC Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence (at the time). His team at SAC were the first to analyse the photos. If anyone has any stories about his career, please contact me. My email is sean.walsh356 “at” gmail.com

Thank you.

My grandfather is Edwin Emerling, pictured on right, next to the General. As I have got older, I have done much research and it is amazing what he and his team members had to go through. Now at 92 years old, he still lights up when there is conversation of his military service. Thanks to him and all service personnel, we are a free nation. Thank you for your service and being my grandfather… I love you.

Nathan, I am author of a recently published book on the 4080th SRW and the Cuban Missile Crisis. We thought your grandfather had passed. Is he still living?

Please call text or email.

H. Wayne Whitten, Col, USMC (Ret)

(813) 784-6017

Hello,

My dad recently passed away and he served with the 4080th Strategic Wing, at Laughlin AFB, and then in Arizona. I have heard many stories over the years and am just doing some research into his service. I would love if someone would contact me with any memories they might have. His name was John Edward Bolster and he served somewhere between 1959-1963 as a statistical specialist (I think). I would much appreciate if anyone had any memories of him by chance. I hope this is not inappropriate to post here.

Thank you!