Published on November 19, 2012

The history of aviation and military air power are deeply linked. Yet this past is more than just a study of machines and of triumph in battle, rather it is about the men and women whose personal experiences at war were as often courageous as they were tragic. With war comes a darkness that afflicts many, a condition that nowadays is known as PTSD — Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome.

Today’s story is a difficult one to present, yet also one that must be told. We choose to tell it in the shadow of the Spanish Civil War. This is the story of the Yankee Squadron, a group of “volunteers” who arrived in Spain in 1936 to go to war. The Yankee Squadron were a small group of Americans and others who, like Claire Chennault’s AVG (the “Flying Tigers”), traveled overseas to fight fascism and the Nazis. Tragically, those who returned were forever changed — many were afflicted by the shadow of that war.

The Yankee Squadron

In mid-November 1936, a small group of American flyers arrived in Spain to offer their services to the Republican loyalists. They came for varying reasons — some to make good money, others for “adventure”, and all to fight against the creeping advance of “national socialism”, and the different shades of Germany’s Nazi ideology. They were the first in the USA to experience a new type of warfare — a particularly deadly implementation of air power — and one that soon would sweep the globe with terrible ferocity in the opening chapters of World War II. Under the command of Andrés García La Calle, the Yankee Squadron consisted of the following men: La Calle, Castañeda, Ben Leider, José Calderón, James “Tex” Allison, Frank Tinker, Harold “Whitey” Dahl, Albert “Ajax” Baumler, Charles “Tiny” Koch, Pepito “Chang” Sellés, Bercial, Ortiz, Gil and Riverola.

Arrayed against the men of the Yankee Squadron and other Republican Loyalist pilots were the Spanish Nationalist air force, in turn strongly reinforced by Nazi Germany’s Condor Legion. The new Luftwaffe came equipped for battle with their new Messerschmitt Bf 109D fighter planes, Heinkel He 51s and Ju 87 Stukas. They were joined by aircraft and pilots of Mussolini’s fascist Italy, including SM.81 bombers and Fiat CR.32s.

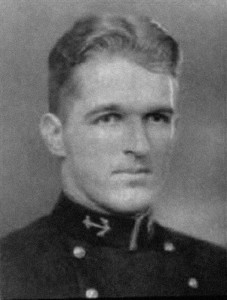

Among the Americans in the Yankee Squadron was Frank G. Tinker, Jr. Like the others, he took on a nom de guerre — his was “Francisco Gomez Trejo”. A graduate of the US Naval Academy, Tinker was a brilliant airman and deeply schooled in the military arts. Unlike his classmates, however, Tinker had a wild and untamed spirit. He brawled and fought and, in the eyes of the elitist US Navy, was not fit to continue as an officer. After a little more than a year since his graduation from Annapolis in 1933, he was thrown out of the US Navy. Shattered, he went to sea working on a merchant ship, but soon found that unsatisfying — and he returned to take up flying.

Tinker’s wild spirit, however, was also the sign of a ruthless, expert combat pilot. Without a job, Tinker accepted the Spanish Republican offer of pay at a rate of $1,500 a month plus $1,000 per enemy airplane that he downed. After arriving in Spain, he spent three months with the others preparing for combat in the Republican air force’s Soviet-supplied airplanes, the Polikarpov I-15 Chato and I-16 Mosca, called the “Rata”, or rat, by the Nationalists. A poor match against Germany’s Messerschmitts, these types were the best the Republicans had — and they had too few of them at that.

It wasn’t long before Tinker had his first experiences in combat when the Yankee Squadron entered combat on February 7, 1937. Before achieving his first successes in the I-15, Tinker was shot down on February 16, 1937. He survived, however, and returned to combat. Losses in his unit were heavy as they were outnumbered by largest superior enemy aircraft. Yet with each engagement, the survivors gained experience.

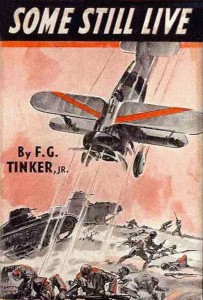

On March 14, Frank Tinker took off from Guadalajara in his I-15 (CA-056) and downed his first enemy aircraft, an Italian CR.32. Thereafter, he began a long and hard series of flights that ranged from strafing and bombing missions to bomber escort and fighter sweeps. With each mission, he experienced horrific scenes of violence and the raw carnage of combat turned him into a hardened instrument of death. He related those experiences in a book he subsequently wrote after his return to the USA, entitled, “Some Still Live”:

“We made our rendezvous with a squadron of our big bombers, each carrying about a half-ton of demolition bombs, over Alcala. There were about 24 of them. They lumbered into perfect position over the enemy lines and let go…. A mile and a half of enemy trenches went up in the air. As soon as they had finished their work Jose’s squadron went down and bombed. As soon as they got back we went down and dropped our own bombs and also threw in a little machine-gunning. As we were going down in our dive I could see our tanks charging up to attack the demoralised Italian troops all along the lines which had been bombed. The Italians started running down the three roads which converged with a fourth at a crossroad. Just as the traffic jam was at its thickest six bombers sailed majestically out of the clouds overhead and bombed the crossroad…. The slaughter was terrific…. I saw several huge trucks spinning through the air, end over end, with men flying out of their open rear ends. As soon as the smoke settled we went down and machine-gunned the survivors.”

Reading between his descriptive lines, we can catch a glimpse of a man writing to cleanse himself of his memories of combat. Between missions, he would drink himself drunk with other deeply affected American volunteers, including the famous author Ernest Hemingway, who helped Tinker with his writing while he himself penned his famous book, “For Whom the Bell Tolls”. Perhaps both men’s trauma should be best recognized today as symptoms of PTSD — though clearly, this cannot be diagnosed historically. Nonetheless, the shadows of war were drawing Tinker into a dark and deeply personal night.

“I could see the individuals plainly; they had also become aware of my presence. I could see dead-white faces swivel around, and, at sight of the diving plane, comprehension would turn them even whiter. I could see their lips drawing back from their teeth in stark terror. Some of them tried to run at right angles, but it was too late: already they were falling like grain before a reaper. I pushed the rudder back and forth gently, so that the bullets would cover a wider area. I pulled out of the dive about twenty feet off the ground, zoomed up to rejoin the squadron, and started looking for more victims. We kept this up until our gasoline and bullets were so low that we were forced to return.”

The End of the War

Just seven months after his first combat mission, Frank Tinker flew his last mission on July 29, 1937. He and the other surviving Americans returned to the USA. Some were in trouble with the authorities for their mercenary contracts. Most were nearly broke, having been underpaid by the losing side. The Republican government had fallen to Franco’s Nazi-backed forces. Tinker was officially credited with 8 air-to-air victories, though he recorded 19 kills in his own flight records, making him the leading ace of the Yankee Squadron. In the war, he logged just 191.3 hours of flight time. The Republicans refused to credit his kills not because they were unverifiable, but because then they did not have to pay the $1,000 bonus per downed plane. They did the same with all of the American pilots. Among Tinker’s kills was the first Messerschmitt Bf 109 downed by an American — in fact, he shot down two of this new and advanced type, just four days apart from each other.

The Last Casualty of the Yankee Squadron

Frank Tinker’s demons hung on in the months after the war. One of his friends, another pilot with the Yankee Squadron, had been downed and captured by Franco’s forces. He was sentenced to death in Madrid. This weighed heavily on Tinker’s mind. Others he knew were in bad shape too — their money problems were severe. He recalled the names of those with whom he had flown and remembered the faces of those who had died. Above all, he recalled the scenes of his combats, including the faces of the enemy’s whose gaze of stark terror reflected in his mind’s eye as he strafed and killed with his guns in repeated flashbacks and nightmares. Yet he was in America, a country at peace and with a strong isolationist streak. This too caused him pain — there was not much call in the late 1930 for a man whose finest trade was as a ruthless fighter pilot.

In the Spring of 1939, Frank Tinker heard through some friends about the American Volunteer Group that was forming under Claire Chennault to go to China and fight the Imperialist Japanese — this unit would be known later as the Flying Tigers. Tinker’s application to the unit was accepted and soon he received a letter confirming his admission from Claire Chennault himself. Just days later, with that letter still at his side, he contemplated a return to war and to once again come face-to-face with dark experiences that plagued him. He drank his last whiskey and decided that that future was not to be — his memories were hard enough already.

On July 13, 1939, nearly two years after his last combat mission over Spain, he was found later dead by his own hand, his pistol nearby. In the end, Frank Tinker became the last casualty of the Yankee Squadron. He was one of America’s greatest aces yet also almost certainly a victim of PTSD.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Frank Tinker’s friend and fellow pilot — the man who had been captured by the Nationalists was awaiting his death sentence — was named Harold “Whitey” Dahl. At the time of Frank Tinker’s suicide, Dahl was still in prison in Spain, yet Dahl would not be killed by a Nationalist firing squad after all. Incredibly, General Franco relented after he received a personal letter from Dahl’s wife, Edith Rogers, a beautiful actress who had been a singer with Rudy Vallee’s orchestra. With great emotion, she pleaded for his release. To help convince the General, she enclosed a photo of herself, hoping it would sway the newly victorious leader of Spain to pardon Dahl and the others from their death sentences.

The letter and photo worked its magic on Franco, who considered the bleak future that would await such a beautiful woman after the death of her husband. Ultimately, he released all of the men. It was a rare show of emotion for a man who would later rule Spain with the power of his newly established dictatorship. Years later, well after Dahl had returned to the USA and thereafter volunteered to fight against the Germans with the RCAF, it was revealed the Whitey Dahl’s “wife” was, in actual fact, not his wife after all. Rather, she was an obviously brilliant actress. Edith Rogers had decided to do her part to save lives in the only way she knew — and thus, as the world descended into chaos and war, Edith Rogers played her finest role, not upon a theatre stage, but in the rarified atmosphere of global politics.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

The German Condor Legion included many aces — but they were not alone helping the Nationals. As well, the Italians fought for the Nationalist cause, bringing their Fiat fighters and other aircraft to Spain. What were the views of the pilots of the Yankee Squadron members of the relative skills of the German and Italian pilots against whom they had fought?

A gripping story!

Frank Tinker could not have heard about Claire Chennault’s AVG forming in the spring of 1939. FDR did not sign the secret executive order authorizing recruitment until April 1941.

“After arriving in Spain, he spent three months with the others preparing for combat in the Republican air force’s Soviet-supplied airplanes, the Polikarpov I-15 Chato and I-16 Mosca, called the “Rata”, or rat, by the Nationalists. A poor match against Germany’s Messerschmitts, these types were the best the Republicans had — and they had too few of them at that.”

First of all, yes, there were a lot of them, and yes they were a match for everything the rebels had except the Bf-109. The thing is, if the Yankee squadron left in july 1937, they didn’t have to fight that much against Bf 109 (the only plane truly better) since some of the Condor legion squadrons were still equipped with Heinkel He 51. Frankly, this sounds a little too much like Hollywood.