Published on January 27, 2013

One hundred years ago this week, the Royal Aero Club’s newsletter “Flight” carried a fascinating report on the essential accessories that every pilot should own. These included moving maps, intercom systems, scarves, flight suits and maintenance coveralls. If that list sounds somewhat familiar, it is probably because we wrote it using the modern equivalent terms. Setting back the clock 100 years, of course, you’d be seeking out dealers for the “Roold map case”, a set of “audiphones”, “mufflers”, “flying suits” and “boiler suits”. It was all a rather new business, you see, and the terms hadn’t quite matured.

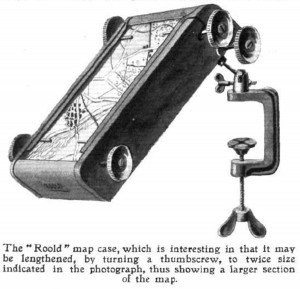

Just what constituted a moving map back in 1913? That’s a good question, after all, that was an era long before digital mapping and consumer electronics.

The “Accessories for the Aviator” Report

The report in Flight was largely drawn from a new catalog that was to be published soon after January 1913 by the General Aviation Contractors, Ltd. (G.A.C.), a contemporary supplier of equipment for aviation. It covered the high points, discussing the items that every aviator really should need and highlighting those that were extravagant “extras”, but would be really good to have. As the following are excerpts make clear, the more things change, the more they stay the same:

We have received the General Aviation Contractors, Ltd., a proof of a very interesting catalogue they are about to issue. It sets forth the main characteristics of the many useful accessories relative to the proper clothing of the pilot, that Messrs. Roold, of Paris, for whom the “G.A.C.” are agents, manufacture. The “Roold” safety helmet is one which is, perhaps, the best known in France. Over here in England, too, it is just as popular. Its construction is rather interesting. It has two strong shells made from a composition of cork and rubber, and between them metallic wool is packed. Outside it is covered with a washable material, so that it can always be brought back to a presentable appearance if it becomes soiled; inside it is carefully padded so that the helmet shall rest comfortably on the head. They are supplied now with a neck extension if required, and with a peak.

At this juncture, the writer felt it important to reiterate the importance of wearing a proper, protective helmet as a key safety item — arguing much like is done to modern day motorcyclists:

Regarding the utility of the safety helmet, there can be not the slightest doubt. Many have been the accidents in which the life of the pilot has been saved by his helmet. It is curious, but nevertheless a fact, while on this point, that pilots in the past have had a dislike to wearing helmets. Perhaps it is that people who run risks never like to be reminded of them. Perhaps they disliked the helmet as being rather too conspicuous. That may be, but, after all, it is wiser to be prepared.

Feeling that the point needed further emphasis, he relayed then a personal story regarding the effectiveness and justification for a flight helmet:

The writer remembers an incident which has some bearing on this point. At the Bournemouth aviation meeting in 1910, Morane’s friends, just before he started out on his flight round the Needles, were trying to get him to wear a helmet. He said he didn’t like to — he preferred his check cap. No one else was wearing one — why should he? So his friends to Christiaens and, after much prevailing, at least got him to consent to wear one, so that they could point him out to Morane and get the last named pilot to wear his. Whether Morane did put his on or not the writer doesn’t remember. But it was lucky Christiaens did, because soon after, flying with a passenger on his machine, he came down heavily on rough ground and was hurt. There was a nasty gash in his helmet. He can buy a new helmet, but he couldn’t have bought a new head. Christiaens had cause to be thankful to Morane’s friends.

The writer then examined some of the items that were in the catalog that deserved special mention:

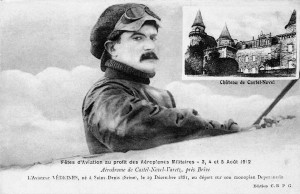

But to coming back to the catalogue. A page or two further on, flying suits are illustrated — seventeen different styles in all — from suits of cat skin, suits of that thin shiny material, Papier du Japon, which Vedrines and Bielovucic wear, to the ordinary blue cotton boiler suits for mechanics. Quite an innovation are the chest and leg protectors that are made on the same principle as the helmets, and which are worn to prevent broken bones. There is also listed a special form of aeroplane seat of a similar character. Of goggles there is a large selection and one model, which brands the list as being well up-to-date, is specially devised for hydro-aeroplane work. It is fitted with a special shield which prevents the glasses from becoming splashed.

Ah, to have seen the “shiny material” of the Papier du Japon flight suits! As well, I wonder what “cat skin” is? Perhaps we really don’t want to know that, actually. The writer continues:

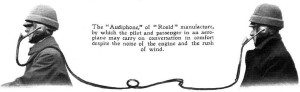

Then there are map cases, gloves, boots, mufflers and all manner of things listed which will be of undoubted interest to the flying man, especially during this cold weather. Lastly, for 3 12s. 6d., the passenger carrier can buy an “Audiphone,” which he can attach to his and his passenger’s helmet and, with it, carry on conversation in comfort, undisturbed by the noise of the motor. Altogether, the list is quite interesting and many pilots will, without question, see in its pages something they may fancy. The General Aviation Contractors, Ltd., will, undoubtedly, be pleased to send a copy to anyone interested.

Conclusion

Looking back, though aviation has come a long way, the essential equipment really hasn’t changed that much. Some things are less essential than before — flying helmets for a day out in your Cessna? And of course, a fine silk scarf does look good and carries a certain “je ne sais quoi”. So too, flight suits are no longer in vogue for anyone except those in the military. That seems a sad thing in some respects, particularly given the unsuitability of street clothes for summer flying when climbing to altitude — and those pen-holders at the shoulder, extra pockets at the chest, knees and shins are certainly handy when flying!

In any case, the terms describing the products have changed over the years. We can forgive our distant aviator ancestors for their rather unique conception of the English language — after all they were English! And even now at this writing, people across the UK still drive on the wrong side of the road, call a car’s trunk at the back a “boot”, a car’s hood at the front a “bonnet”, the engine’s muffler a “silencer” and far worse! I’ve heard tell even that after so many decades they still can’t can’t say the word “aluminum” correctly (rather saying something like “al-ooo-min-ee-um”, even if there isn’t an extra “i” in there if you look closely…).

Ha! So there you have it — written by a true American aviator! I just love teasing our English friends a bit (except for you, Kim Tipple out at Lasham, because you’re one of the best glider pilots I’ve ever met)….

One More Bit of Aviation History

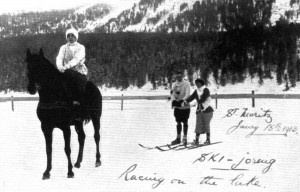

The famous British aviator, Claude Grahame-White, had a bit of an accident in late 1912. As part of his recovery, he took a vacation to St. Moritz where he enjoyed some time with his wife and other aviator friends. In fact, Santos-Dumont and a number of other well-known pilots of the day came along. Among the sports they enjoyed while relaxing in St. Moritz was “ski-joring” which appears to have gone out of style. Based on the photograph (see above), it involves donning skis and being towed behind a horse by a rope attached to a small bar, somewhat like modern day water skiing!

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What ever became of General Aviation Contractors, Ltd., the “Sporty’s Pilot Shop” of its day?

Hang on! We DO spell aluminum with an ‘i”: aluminium — hence the different sound!

Marty in Oz

Oh, that is interesting. To solve this then once and for all, let’s look to the origins of aluminum. The metal was postulated by multiple scientists in the early 1800s. Britain’s Sir Humphry Davy initially named the metal in 1807. Hans Christian Oersted of Denmark first isolated it in 1825, then Friedrich Wöhler, a German, developed the process processes to extract it in larger quantities in 1845, which was advanced by Henri Étienne Sainte-Claire Deville, a Frenchman, in 1854. Finally, the process was perfected and patented by Charles Martin Hall, an American, in 1889. Hall went on to found the company that would become ALCOA, one of the largest aluminum companies in the world.

I did find this: “Sir Humphry made a bit of a mess of naming this new element, at first spelling it alumium (this was in 1807) then changing it to aluminum, and finally settling on aluminium in 1812. His classically educated scientific colleagues preferred aluminium right from the start, because it had more of a classical ring, and chimed harmoniously with many other elements whose names ended in -ium, like potassium, sodium, and magnesium, all of which had been named by Davy.” — Michael Quinion

If this is true, then English have themselves to blame for both spellings!! An interesting bit of history.

I say… is that why Yanks and Brits are known as “two nations separated by a common language?

Jim A., Tucson, AZ

How do we find out the answer to the Mystery aircraft?