Published on January 22, 2013

For decades, conspiracy theories have abounded about secret Nazi UFO bases in Antarctica, about secret U-Boat missions, and about Hitler surviving the war and holing up in an ice cave. In recent times, these themes have even been picked up by Hollywood to the extent of putting the Nazis into UFOs that colonized the Moon. Each story seems to vie for the title of most bizarre and unbelievable. Yet the stories have a grain of truth to them — Nazi Germany really did mount a major expedition to Antarctica on the eve of World War II, in 1939, though few are familiar with the history. Before you jump to any conclusions, know that the goal of the expedition was not military, but rather part of Germany’s efforts to free itself from the Norwegian stranglehold on the world supply of whale oil!

The Third Germany Antarctic Expedition

In the 1930s, whale oil was a key commodity and in high demand — even more so than gasoline. Whale oil was a key ingredient in a wide range of civilian products that were in routine use, such cleaning solutions, soaps, lamp oils and even margarine. Germany found itself by the late-1930s importing as much as 220,000 tons per year from Norway. This was a serious drain on foreign reserves and put downward pressure on the value of the Deutsche Mark. Thus, as strange as it might seem to modern ears, developing a German whale oil industry was a strategic economic goal for Germany. Further, the Nazi Government knew that it had to free itself from such financial burdens in order to undertake its war plans.

Germany began with the manufacture of 50 whaling ships and seven factory mother ships to begin domestic production. It quickly became apparent that to service the industry, a whaling station would need to be constructed along the coast of Antarctica, where the most plentiful whales were found. Likewise, sufficient land would have to be claimed to ensure German rights to territorial waters and resource rights. Thus, in December 1938, Germany launched its Third Antarctic Expedition, commanded by Alfred Ritscher, a noted German Arctic expert — the expedition arrived off the coast of Antarctica on January 19, 1939.

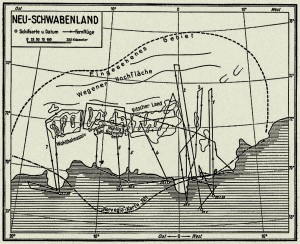

To support the mission, a seaplane tender that was owned by Deutsche Lufthansa AG, called the MS Schwabenland, would service two of Lufthansa’s Dornier J Wal seaplanes, named Passat (D-ALOX) and Borea (D-AGAT). A set of large ice arrows that measured 1.2 meters in length were constructed to mark the territory — they had a point at one end and a set of stabilizer fins on the other that each carried a swastika. These were to be air-dropped from the Dornier J Wal seaplanes into the Antarctic landscape, thus marking the edges of the explored area to define the border of what the Nazis decided to call Neu-Schwabenland. This land would be defined by the latitude-longitude zone of 60 degrees and 74 degrees South and 11 degrees to 20 degrees East.

The Flights of the “Passat” and “Borea”

In all, there were seven daring flights during the Third German Antarctic Expedition from January 20 to February 5, 1939. Each was carefully planned to cover wide swaths of territory with a minimum of overlap. Expert navigation was needed so that the Dornier J Wals could accurately map the landscape. Photographs were taken at regular intervals as they flew. At the end of each mission, the seaplane had to return safely to the seaplane tender, MS Schwabenland. Rudolf Mayr and Richard Heinrich Schirmacher commanded the Dorniers “Passat” and “Borea” respectively. They performed flawlessly and the operation covered 350,000 square kilometers of surveyed territory.

If there had been a problem during one of the flights that had forced one of the planes down, the chances of rescue would have been minimal and urgent, given the short duration of the Antarctica summer. The flight crews brought extensive supplies and equipment so that they could survive for a time and try to make the coast, but such an event would have resulted in major disruptions to the overall expedition, transforming it into a rescue operation instead. Thankfully, nothing went wrong.

Incredible Discoveries

At the outset of the mission, even before the German expedition arrived, the Norwegians apparently heard word of the ship and planes. Without delay, they laid claim to the very lands that Germany intended to declare as its own. The Germans were to dispute Norway’s claim since the Norwegians truly had no idea what features might be found in that section of the Antarctic landscape, nor even had an accurate map of the coastline. Everyone envisioned a flat, largely featureless, ice-covered wasteland punctuated by large mountain ranges — they were wrong.

Inland, the Germans made amazing discoveries. In Neu-Schwabenland (as they called it), an ice-covered landscape gave way to clear ground with a vast mountain range and open lakes, with water that remained unfrozen. They viewed this as an Antarctic oasis deep inland in the south, which the Germans named the Schirmacher-Oase (Schirmacher Oasis). A large mountain range was charted and photographed in detail — and named by the Germans the Wohlthat-Massiv. These names remain in use even to this day.

Final Thoughts

In the end, the Germans may have named the lands they had explored Neu-Schwabenland, but they never made proper and formal claim to the territory. Before the maps could be finalized, World War II had broken out and the German whaling fleet’s operations were curtailed. When Germany invaded Norway, they managed to solve the whale oil problem in a different, more aggressive way. Nonetheless, whaling operations were still limited throughout the war, resulting in shortages.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What became of the two Dornier J Wal aircraft, the “Passat” and “Borea”?

From the Historic Wings Archives

G1 Down in Antarctica: Operation Highjump and the crash of a Martin PBM-5 Mariner in Antarctica, leading to a 14 test of survival during an ill-fated American expedition to map the frozen continent.

I would be interested in receiving good quality (300 dpi) copies of the map and pictures used in this The Nazis in Antarctica.

Cheers,

Dirk

The mentioned unfrozen lakes where discovered by my goodfather Lufthansa Flight Captain Richard Schirmacher (My second middlename is Richard). The lakes got his name “Schimacher Oasis”.. He was the pilot of the Dornier 10 t J Wale D AGAT Boreas (not Borea: it’s Greek for .the god of the north wind).

Thank you for your geat FLIGHT STORY!

Clauss

Sehr geehrter Herr Leibrock,

Mit grosses Interesse habe ich Ihren Beitrag gelesen denn ich wollte mehr wissen über Richard Heinrich Schirmacher, da er im Zweiten Weltkrieg noch einige Monaten in der Nachtjagd tätig war auf Fliegerhorst Venlo in meine Heimatstadt. In Erinnerungen einer seiner Kameraden wird gesprochen dass er seine Kameraden unterhalten hat mit Geschichten úber seine Antarktik-Abenteur.

Dear Mr. Leibrock,

With great interest, I read your contribution because I wanted to know more about Richard Heinrich Schirmacher, since he was in the Second World War for a few months involved in the night war and was active at the airbase Venlo, which is in my hometown. One of those who knew him then said that he entertained his comrades with stories about his Antarctic adventure.

Freundlichen Grüssen sendet Ihnen,

drs. Marcel A.L.M. Hogenhuis

Kaldenkerkerweg 10

5913 AD Venlo

Niederlande

tel. 0031-77-3200914