Published on March 9, 2013

The phrase “”More lost than Lieutenant Bello” (“Más perdido que el Teniente Bello”) is a part of Chile’s linguistic heritage and refers to someone who loses their way quite badly. Yet where did the phrase come from? Well, it turns out the “Lieutenant Bello” saying pays homage to an early aviator whose full name was Alejandro Bello Silva and who was one of the Chilean military’s very first military pilots. As you might imagine, Lt. Bello did indeed get lost while flying — so lost, in fact, that his airplane and his body have never been found, even to this day.

This is the story of the mystery of Lt. Alejandro Bello Silva’s disappearance. 99 years ago today in aviation history. On March 9, 1914, Lt. Bello took off into the fog and clouds on his final flight to qualify for his military aviator wings — and simply disappeared.

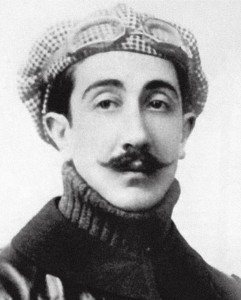

About Lt. Bello

2nd Lt. Alejandro Bello Silva was a dashing young soldier in the Chilean military who hailed from the town of Ancud, Chile. Though his father had been banished during the 1891 Chilean War, the young son was loyal to the government and joined the military. His goal was to become a military pilot and, as such, he attended the Chilean military’s flight school at Lo Espejo Aerodrome. A good student, he advanced quickly toward receiving his military wings.

The last flight remaining for him before graduating the course would be a cross country — he would have to fly from Lo Espejo Aerodrome, which was located in central Chile, directly south a short distance of just 5 miles to Culitrín Aerodrome, and then from there, without stopping, fly almost directly east to Cartagena, Chile, on the western coast, a distance of 53 miles. He would then return to Lo Espejo Aerodrome, the same distance of about 53 miles on the return leg. Along the way to and from Cartagena, the mountains of central Chile crossed the flight path. This meant that the pilot would have to fly at higher altitude to surmount the ridges.

In other words, the flight was a reasonable challenge for a cross country in an era when the planes the Chilean military averaged a cruise speed of perhaps 50 mph and mountain flying was a basic, required aviator skill. At 111 miles in total distance, the cross country flight should have taken just a little more than two hours.

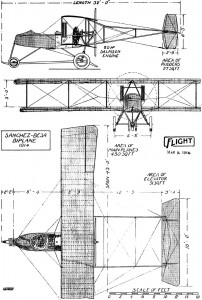

Lt. Bello’s Aircraft

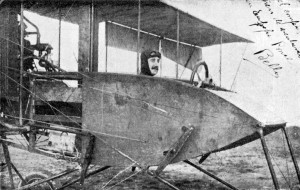

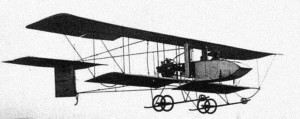

That day, Lt. Bello would fly one of Chile’s new Sánchez-Besa 1914 biplanes. Historians are uncertain whether the Chilean aviator, José Luis Sánchez-Besa, truly designed his own plane or simply modified a Voisin design with a few refinements, but in any case, the Chilean military had acquired some of the planes for its new air force. The plane’s modifications included a larger fuel tank that would give the plane a 4 1/2 hour endurance, an enclosed cockpit and an 80 hp Salmson engine. A review from Flight, highlighted the key features of the Sánchez-Besa biplane of 1914, in which Lt. Bello flew. The reviewer stated that its minimum speed was 35 mph and that the airframe had a maximum speed (presumably in a dive) of 65 mph. It weighed 1,750 pounds empty, making it a rather sizable craft.

Superstitions among pilots are commonplace and thus it is worth noting that the plane that Lt. Bello flew on that fateful morning was numbered “13”, considered by many to be an unlucky number. Like many planes of the day, it carried a name as well, reflecting its honored position in the new military air force. It was called the “Manuel Rodríguez”, after Manuel Rodríguez Erdoíza, the famous Basque who helped lead the guerrilla war for the liberation of Chile.

The Last Flight

In the predawn hours of March 9, 1914, Lt. Bello arrived at the Lo Espejo Aerodrome. He was slated to fly the cross country flight with another plane, this one carrying another student and an instructor. Lt. Bello was initially in a different plane (tail number unknown) and the two planes took off into the low hanging clouds and fog. Quickly, they realized that to attempt the journey in such conditions was not viable. They circled closely back and landed, lucky to have found the airfield. The short flight was not without mishap, as Lt. Bello managed to damage the landing gear on landing. Otherwise, the three aviators had come through it okay.

They waited for a time for the weather to lift and, suspecting that it was clearing, they once again mounted their planes. This time, Lt. Bello was in #13. After starting the engines, the two planes again took off and quickly entered into the low cloud. Immediately, however, the instructor and student pilot realized that they had a serious fuel problem — they had to return immediately lest they exhaust their fuel and have to crash land. As it happened, they made the airfield just fine.

As for Lt. Bello, he continued on alone, disappearing into the cloud on a southerly heading en route toward Culitrín Aerodrome. Almost certainly, he made the turn point there — the heading was almost directly south and the time aloft would have been just 6 minutes. Then he would have turned west toward the most distant checkpoint, the city of Cartagena along the shores of the Pacific Ocean. He was never seen again.

The Search and the Mystery

That very day, when Lt. Bello did not come back to either Culitrín or Lo Espejo Aerodromes, the Chilean military launched an extensive search. The best theories were that the plane had crashed into the mountains en route or that he had overflown Cartagena in the clouds and gone out to sea before the engine failed, forcing him to ditch into the ocean waves. Despite extensive efforts, however, no trace of the plane nor of Lt. Bello was found. After a time, having searched the mountain passes and combed the beaches for any debris that might have washed up, the military gave up the search — Lt. Bello was lost and presumed dead.

In the years afterward, many people have launched searches to see if they could locate a crash site in the mountains between Lo Espejo and Cartagena. A large expedition was launched in 1988, but like the others, it too came back empty-handed. Whatever happened to Lt. Bello, his crash was either so remote and hidden as to be impossible to find or his plane had sunk to the bottom of the ocean offshore somewhere in an arc of perhaps 125 miles around Cartagena, with that number being based on the fuel available.

Final Notes

In 2007, another search expedition was lead by Jorge Ponce of the Club Aéreo de San Antonio. This time, the searchers set out in the Cuncumén hills about 10 miles south of Lt. Bello’s flight path to look for pieces of the plane. In 1914, in the days and weeks after the loss of Lt. Bello, among many reports from Chileans who claimed to have heard the plane, one had come in from a woman in that same area who said that she had seen the plane crash. In 1914, like the other reports, her account was evaluated and eventually discounted.

Indeed, two pieces of highly corroded aluminum, which would correspond to the enclosed cockpit of the plane, had been found in that very area during the 1980s. Although earlier analysis of those pieces was inconclusive, the new search sought to follow up on the find and locate more pieces of the Sánchez-Besa biplane or, it was hoped, the bones of Lt. Bello. As it happened, over three days in November, the search groups were unable to search as effectively as they wished due to threatening wildlife in the area.

Maybe, just maybe, something of Lt. Bello ill-fated flight might have been finally found. In any case, until something else emerges that proves the case, the phrase, “More lost than Lieutenant Bello”, will continue to hold onto its full and very sad meaning.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

How many of the Sánchez-Besa biplanes did the nation of Chile acquire for its new air force? How well did they perform?