Published on April 26, 2013

From the first minutes with the launch Operation Rügen, the bombs began to rain down indiscriminately on the small Basque town of Guernica. No effort was made to avoid civilian areas — in fact, the deadly intent of the Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion was to utterly destroy the town itself and kill the majority of its inhabitants. The date was April 26, 1937 — today in aviation history — and Spain was embroiled in a civil war, pitting Republican Forces against the Nationalist Forces of Franco, with the aid of the German Luftwaffe and the Italian Aviazione Legionaria. The attack on Guernica established that the Luftwaffe was unfettered from the shackles of arms limitations codified in the Armistice that had ended World War I. Moreover, it demonstrated to the world the true destructive potential of a new generation of air power. Indeed, the events at Guernica cast a dark shadow that presaged the coming horrors of World War II, a war that was but two years in the future.

The Attack

To support the operation, the Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion and the Italians deployed only a few dozen aircraft, though these attacked in six consecutive waves, beginning at 4:30 pm. The first wave involved a single Dornier Do 17 that dropped twelve 50kg bombs. The Italians performed the second wave with three SM.79s from the Corpo Truppe Volontarie. These dropped another 12 bombs each. The third wave was flown by a single Heinkel He 111, which was accompanied by five Fiat C.R. 32 fighters from the Aviazione Legionaria. Then the fourth and fifth waves were performed by two German Heinkel 111 bombers in each. The fifth wave completed its attacks at 6:30 pm. At that point, The damage was extensive — but it was just the beginning that day for Guernica, on April 26, 1937.

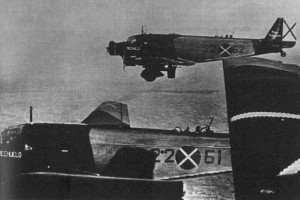

The sixth wave followed over the next 15 minutes, ending at 6:45 pm, and would prove to be the most devastating. These last planes came in multiple V-formations of three Ju 52 trimotor bombers each. These were the bomber versions of a German airliner design that during WWII would be more widely known as a cargo and paratroop transporter. The Ju 52s simply flew across the town’s center from south to north, dropping their bombs from line abreast formation — this was a first test of the new type of terror attack called carpet bombing, relying on a mix of 250 kg bombs and the Luftwaffe’s new ECB1 incendiaries. Simultaneously, Messerschmitt Bf 109B and Fiat fighters provided escort and engaged in extensive strafing of the civilian populations on the roads. This completed the campaign planned for the day.

Casualties and Damage

In the wake of the attack, news reports varied widely about the true number of casualties inflicted. For many years, the number was set at approximately 1,600 killed and 800 wounded. Propagandists sought to present higher or lower casualty figures, twisting the numbers in the way that favored their cause. The Germans made claim to perhaps 300 killed. The Franco Government, years later, would put the figure as low as 12 dead (this was claimed in 1970!), demonstrating the widely divergent approaches to describing the events.

Certainly, many were killed — undoubtedly hundreds. As it was, civilians fleeing in panic on the roads leading from the town were strafed mercilessly. Dozens, if not even more than 100 were killed just there. Based on careful research, it is now widely accepted that at least 300 to 500 died at Guernica. As well, nearly three quarters of the town was destroyed, much of it burned from the incendiary bombs. Later too, this would be a matter of dispute — not the scale of the destruction, but rather who had done it. The Nationalists would claim that fleeing Republican soldiers had deliberately torched the town — a bald-faced lie, but one that was not without precedent in any case, as that had happened at other villages in the past year.

Records showed that the Condor Legion dropped an astonishing 99,207 pounds of bombs into the town’s center that day. The damage inflicted, as one might imagine, was beyond any expectation. Modern warfare had made its debut — and it was terrifying. April 26 was a Monday, which was the weekly market day in Guernica, and thus, farmers and others from the surrounding area had gathered in the downtown square, shopping and meeting with one another. The town’s population that day had swelled to probably around 10,000 as a result — most were in the open in the center of the downtown area when the bombs began to fall.

Terror Bombing

Although the attacks had been the first “carpet bombing” raids meant to terrorize the population, it wasn’t until many years later at the post-war trial of Hermann Göring that this would be admitted. The Nationalist Government had ordered the bombing and the Germans had used Guernica to test their new theories of terror bombing raids, introducing carpet bombing. Guernica was practice against a small, undefended target amidst a larger war.

The success of the Condor Legion at Guernica would influence the later attacks by the Luftwaffe on Warsaw and many other towns and cities in the East, as well as initially in the attacks on France and the Low Countries. The terror bombings of the Battle of Britain and later terror weapons that rained down across the south of England in 1943 to 1945 were derivative of the lessons learned at Guernica. The only difference would be one of scale — a few hundred killed vs. tens of thousands later on.

Final Words

The Luftwaffe’s official policy stated that terror bombings were generally counterproductive, since they could reduce the effectiveness of the propaganda war and turn the population against the German advance. That policy had been in place prior to the attacks on Guernica, but the Condor Legion had done the raid anyway. The results were carefully evaluated and categorized into formal reports, which in turn guided Luftwaffe training and tactics. While Guernica’s destruction was extraordinary, it would pale in comparison to the mass destruction that followed.

Later air forces throughout World War II and beyond would learn the lessons of war from this one day — carpet bombing tactics would be employed not just by the Germans, but as well by the US, the British, the Soviets, the Italians, and the Japanese, among others. The shadow of Guernica was a long one indeed.

My mother, Justa Urraza Larrea, witnessed the shooting down of the German pilots over Bilbao. One of them bailed out with a parachute and landed on the side of Artiva Hill. My mother then ran to the site from her house in Aldana. She saw the pilot being arrested and later cut off a piece of the parachute to use in making a pillow case. I would like to ask if anyone knows the name of the German pilot who survived?

Thanks in advance!