Published on April 27, 2013

Since 1911, the Pommery Cup prize had been standing, a twice yearly competition with a large prize of 7,500 francs given each six months until the last competition in the Fall of 1913. Thus, two prizes were awarded each in 1911, 1912 and then 1913. A total of 50,000 francs were given away, with the final competition being the largest purse — 12,500 francs! The rules were simple enough, at least on the face of it, being that, as reported by Flight, “It was stipulated that to qualify flights must be made in a straight line, in one day, and at a speed of not less than 50 kiloms. an hour.” The prizes were awarded for the periods ending April 30 and October 31 in each year. Not surprisingly, as the final weeks of each prize period approached, the number of competitors making attempts picked up.

Thus, 100 years ago today in aviation history, the Pommery Cup prize of Spring 1913 was on the line. After this, the fifth running of the competition, the big finale of the Pommery Cup would be awarded in the Fall, with the full size Pommery Cup being given to the final victor. And if Pierre Daucourt and Edmond Audemars had anything to do with it, it would be one of them that would be the victor. With just days left to the end of the prize period for the Spring 1913 period, the two set out, hoping to span the distance from Paris, France, to Berlin, Germany. Only one would make it — but would either win?

Edmond Audemars Begins his Flight

In the early hours of the morning, at 5:15 am, the Swiss pilot Edmond Audemars prepared his Morane monoplane at Villacoublay. Across Paris, though he did not now it, the first preparations were also underway at Pierre Daucourt’s hangar at Châteaufort, where a Borel monoplane was being readied for his flight. The weather had dawned with a glorious perfection that lead both men to conclude that today was the day. Berlin was a far distance away and some expected it was too great to achieve in a single day of flying, even if one’s aeroplane performed perfectly. As it happened, Audemars off first. Both intended to take off soon after dawn so as to maximize their time aloft and, barring any unforeseen weather or problems, reach Berlin by nightfall.

First, Audemars made a fast trip toward Mexieres, France, covering a distance of 210 kilometers in just 1 hour and 25 minutes. He took the time there to check over the engine, refuel and put in fresh oil. At 7:30 am, he launched once more. His next stop, if all worked out, would be in Germany.

Pierre Daucourt Sets Out

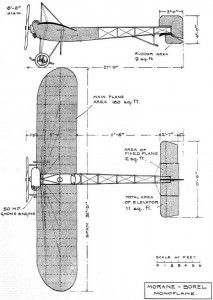

Just fifteen minutes after Edmond Audemars had departed Villacoublay, Pierre Daucourt wheeled his Borel out onto the grass field at the Borel school’s aerodrome located at Châteaufort, Seine-et-Oise, near Paris. The engine was started and with a cheerful wave to his friends, he took off — the time was 5:30 am. At first, he set out in same direction as the other’s Morane, though he did know of the other’s departure, nor would he have expected to catch him even if he did. Instead, Daucourt steered 220 km to Maubeuge and then turned slightly to navigate another 120 km to Ans Aerodrome at Liege, Belgium. He landed there at 7:40 am, having covered 340 km in 2 hours and 34 minutes. Clearly, Audemars’ Morane was a faster aircraft, though it wasn’t the mission to arrive first after all, but to go farthest.

As later computations would show, Daucourt’s Borel was averaging a ground speed of 133 km/hr — not a bad speed for a Gnome-powered 50 hp aeroplane. Comparatively, Edmond Audemars’ Morane was a swift, having averaged a ground speed of 148 km/hr. Both had proceeded from Paris, and both veered north over Belgium.

Edmond Audemars Forges On

Audemars started out again from Mexieres with a take-off at 7:30 am. He flew over the forests of the Ardennes at 1,800 meters of altitude, aiming to cross over in Germany and achieve Wanne in Westphalia by late morning. Yet with just 100 kilometers remaining, the winds picked up and he found himself suddenly fighting to make forward progress. The Morane seemed to be nearly standing still in the skies, though Audemars could see that he was making some progress, though painfully slow. Four hours after departing, he finally landed at Wanne, Westphalia, Germany, at 11:30 am.

He elected to wait for a time to see if the winds abated. Instead, after lunch, he noted that the winds were rather increasing. Nonetheless, the Pommery Cup was on the line — he knew that he had to make a go of it. He fueled and took off, making a spiral climb to altitude, hoping that he would find a level where the winds were lessened. After ten minutes, he returned to land. He would abandon his attempt for the day. Instead, he decided to relaunch in the morning, fly to Berlin and then perhaps continue on further. The weather would decide his journey, he reasoned.

Pierre Daucourt Relaunches

Farther to the south and an hour later, Pierre Daucourt too faced the wind, though it was not as bad as that seen by Audemars. As Daucourt prepared to depart from Liege, Belgium, he made sure his fuel tank was filled and his oil checked. At 9:30 am, he lifted off, aiming to cross into Germany and locate Hanover. Despite the wind, he managed it perfectly, landing there on the horse racing track at 1:45 pm. Looking back, this last leg had seen his ground speed reduced to just 82 km/hr — the headwind had knocked off a stunning 51 km/hr from his forward speed. Again, he checked over his plane and refueled. Berlin was within reach — yet the winds bothered him.

Daucourt too waited for awhile, watching the winds and considering his options just as Audemars was doing at that very time 200 km to the southeast, on the ground at Wanne, Germany. Where Audemars would judge the wind too much, Daucourt chose to depart, despite that his was the slower aeroplane. He had paused for nearly two hours and during that time he adjudged that the conditions would not improve. If he were to wait much longer, Berlin would be out of reach before nightfall. Even with the headwinds, he worked out that he should be there within two hours; if there was a problem with the plane, he would have at least an hour and a half to land, sort it out and take back off to finish before dark.

With the Pommery Cup prize beckoning, Pierre Daucourt bravely set out from Hanover at 3:38 pm, flying into the teeth of a fierce headwind. Turbulence threw his plane up and down as much as 150 meters in altitude as his Borel rocked and was buffeted as he flew along. It took nearly three hours to reach the Johannisthal grounds at Berlin, safely landing at 6:33 pm. On this last leg, his forward speed over the 260 km distance had been just 89 km/hr. It had been a battle, no doubt, but he had made it.

On arrival, he was pleased to find that the Imperial German Aero Club awaited him — Major von Tschudi and top officials were there to greet his arrival and offer him dinner. As he would later figure it, he had covered the full distance of 895 km in 7 hours and 40 minutes of flight time — thus, he had averaged 116 km/hr. His flying time for the distance of 895 kiloms. was 7 hours 40 minutes. As he ate dinner, the sun set a bit less than two hours later (official sunset was at 8:24 pm). Word arrived too from the airfield that there was no news of Edmond Audemars.

Audemars’ Disappointment

Where Daucourt had forged on into raging headwinds, Edmond Audemars had elected to stop at Wanne, still 450 km short of his goal of reaching Berlin. He choose to stop for the night and so, disappointed at the prospect, turned in to get some sleep. The following morning, arriving at the airfield at Wanne, Edmond Audemars was disappointed to find that the winds showed no sign of abating. With a heavy heart, he canceled his attempt. He waited there until the winds tapered off and a couple of days later returned to Villacoublay to hear the news that Daucourt had forged on and made it all the way.

The Pommery Cup Prize Won?

With the Pommery Cup and 7,500 francs on the line, the pilots waited for word of any others who might make the journey before the end of April. Just days remained until the prize winner would be decided. As it stood, with his flight covering Paris to Berlin, 895 kms in total, Pierre Daucourt was the leading candidate for the prize. He rested comfortably, enjoying the moment as the flying world awaited news of whether any other would make a final go of it.

Pierre Daucourt would soon learn that another pilot was preparing another attempt — and thus, it seemed the decision of the fifth and next to last Pommery Cup was yet to be finalized.

— To be Continued —

One More Bit of Aviation History

The first four competitions preceding the flights above, were described as follows in a November 1913 issue of Flight (annotations added for dates, where needed for clarity, in parenthesis):

The first contest ended on April 30th, 1911, and was won by Jules Vedrines, by his flight on a Morane-Borel from Paris to Poitiers, 336 kiloms. On a similar machine he won the second section (October 1911), flying from Paris to Angouleme, 400 kiloms. In the first half of 1912 (April 1912), Bedel, on a Morane-Borel, was the winner, going from Villacoublay to Biarritz, 645.281 kiloms., while Daucourt, on a Borel, won the second prize in 1912 (October 1912) with his trip from Valenciennes to Biarritz, 852 kiloms.

Thus, Pierre Daucourt was no stranger to the Pommery Cup, having won the prize of 7,500 francs just six months before on the very same aeroplane. With that price came not only the money but also a miniature version of the Pommery Cup itself — he imagined having two of those on his shelf, plus winning the final one and earning the full-sized trophy at the end in the sixth competition, which was to culminate in October 1913.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What ever became of Pierre Daucourt?

Killed in WW I perhaps?