Published on April 16, 2013

Harriet Quimby’s flight had been carefully planned. The challenge was nothing less than matching the famous flight of Louis Blériot from 1909 by taking a plane across the English Channel. If successful, she would become the first woman to make the crossing on her own, as the pilot. She planned on taking off from Dover, England, and landing on the beach at Hardelot-Plage, Pas-de-Calais. It was almost exactly the reverse course flown by Louis Blériot himself. The similarities didn’t end there — even her plane was essentially the same type. The flight across was a distance of 25 miles and, with an airplane that traveled at perhaps 30 mph at best, she knew it would take an hour. It was a distance and flight time that she had flown before in America — so long as nothing went wrong, she would land in France in time for a nice breakfast.

As it happened, everything worked exactly as planned, except that the media totally ignored her record-breaking flight. Why was that? Was it because she was a woman flying in the man’s world of that day and age? No, not at all. Instead, there was something else that stole the headlines that morning, on April 16, 1912 — today in aviation history — eclipsing Harriet Quimby’s flight into history.

Harriet Quimby’s Introduction

The Royal Aero Club covered Harriet Quimby’s crossing in their newsletter, Flight, in some detail. They provided more than a simple reduction of the story into its newsworthy terms, but rather added considerable context to her flight. They opened with a wonderful salute to her status as one who should have been better known to England’s leading aviators, but who was not. Perhaps this was because she hailed from the United States, too far from Europe to make the news. The Royal Aero Club writers explained:

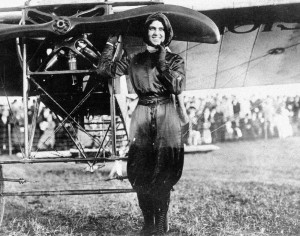

ALTHOUGH Miss Harriet Quimby has made an enviable reputation for herself as a capable pilot in America, her native country, she has not been very well-known on this side of the Atlantic, and no doubt few of our readers who read the announcement in FLIGHT a week or so back that she was coming to Europe, looked for her so soon to make her mark by crossing the Channel.

Earlier, the writers had introduced Miss Quimby in a short item that also related news about other women in aviation:

THE number of certificated aviators among the gentler sex is being gradually added to. The first to obtain her certificate under the new rules was Madame Driancourt, at the French Caudron School, but soon after her was Miss Harriet Quimby, of California, who qualified on a Moisant monoplane at Mineola, N.Y., on August 1st. Miss Matilda Moisant, sister of the late J. B. Moisant, has also qualified for a pilot’s licence on a Moisant monoplane, and Miss Blanche Scott should qualify shortly.

Preparations and Flight

The writers made particular mention of the rapidity with which Harriet Quimby had carried out the record flight — though they got it wrong, she wasn’t from California, but rather from the small town of Coldwater, Michigan. Further, they did not clarify their meaning and it seems that either they were impressed with her confidence and abilities, which made the flight across seem like just another day flying, or perhaps they were making obtuse mention of a certain American impetuousness, using that classic language of British implication:

Contrary to what one would expect, the feat was carried through without any fuss or elaborate preparations, and only a few friends, including Mr. Norbet Chereau and his wife and Mrs. Griffith, an American friend, knew that the attempt was being made and were present at the start. Miss Quimby had ordered a 50-h.p. Gnome-Blériot, which arrived from France on Saturday, and was tested on Sunday by Mr. Hamel.

The flight itself was then described in the simplest terms, though with a certain illustrative flair that, even in its brevity, puts the reader into the cockpit for the flight itself. The phrasing shows that this was clearly written by a pilot, for pilots:

On Tuesday morning, as previously arranged, after Mr. Hamel had taken the machine for a preliminary trial flight, Miss Quimby, who had been staying at Dover under the name of Miss Craig, took her place in the pilot’s seat, and at 5.38 left Deal, rising by a wide circle and steering a course, by the aid of the compass, for Cape Grisnez. Dover Castle was passed at a height of 1,500 feet, and by the time the machine was over the sea, it was at an altitude of about 2,000 feet. Guided solely by compass, Miss Quimby arrived above the Grisnez Lighthouse a little under an hour later, and making her way towards Boulogne she came down at Equihen by a spiral vol plané not far from the Blériot sheds.

Harriet Quimby herself later wrote of the rush at which she had commenced, putting things in a different light: “There was no wind. Scarcely a breath of air was stirring. The plane was hurried out of the hangar. We knew that we must hasten, for it was almost certain that the wind would rise again within an hour.”

Conclusion and Aftermath

The writers made no mention of the lack of news coverage — after all, they covered it well enough themselves, complete with a large half page photograph of Miss Quimby in her Blériot — and thus they offered her the laurels that she so very deserved:

To Miss Quimby, therefore, belongs the honour of being the first of the fair sex to make the journey, unaccompanied, across the Channel on an aeroplane; and, appropriately enough, as the first crossing of an aeroplane by a “mere man” was on a Blériot machine, her mount was of that type. Miss Trehawke Davies, it will be remembered, was the first lady to cross the Channel in an aeroplane, but she was a passenger with Mr. Hamel on his Blériot monoplane.

In light of this, just why was Harriet Quimby’s incredible flight largely ignored by the press and public? Put simply, another news event took place the night before, of which, at the time of her take off, she knew nothing.

On April 15, 1912, mere hours before Harriet Quimby’s departure from Dover, the great ship RMS Titanic struck an iceberg and sank in the North Atlantic. Thus, the morning newspapers lit up with large headlines declaring news of the tragedy. As for Harriet Quimby, she barely warranted mention as a result — it was ill luck of timing, but it did nothing to eclipse her actual achievement that day.

As for what else was not reported about her flight? Well, there was the matter of her all-purple aviation jumpsuit, which she had designed herself….

From the Archives

Miss Trehawke Davies Loops the Loop — read about another daring aviatrice from the same time as Harriet Quimby. In fact, Miss Davies was the first woman to cross the Channel by air, though as a passenger.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Who was the second woman to pilot a plane across the English Channel?

Dear Historic Wings,

Very interesting. Just a quick question, Louis Blériot was the first man to fly the Channel, and Harriet Quimby the first woman, but who was the second man to fly the Channel?

Toodle pip!

Nigel

Well, the way you asked the question not specifying fixed wing powered aircraft, we would have to answer that the first two that crossed were Jean Pierre François Blanchard (France) and John Jeffries (USA) together in a balloon on January 7, 1785. If you meant fixed wing, I think — off the top of my head — that it was Charles Rolls, who did a crossing in BOTH directions on June 2, 1910.