Published on May 10, 2013

When Ernest Failloubaz climbed into the aeroplane, he had never flown before in his life. Further, he had no flight instructor, nor was one available anywhere in all of Switzerland. In fact, he and his compatriot, René Grandjean, were the first two aviators in the country. What Failloubaz knew about piloting he had worked out on his own, in part as well when helping his compatriot Grandjean build the aeroplane. Since February, they had been “ground testing” the aeroplane, running it back and forth across the grass as Failloubaz gained familiarity with the feeling of the controls. The grass field was itself not very smooth and so, as they practiced, the aeroplane would bump and bounce along over the uneven field of l’Estivage, on the outskirts of Avenches.

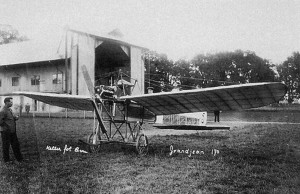

If that wasn’t dicey enough, the aeroplane too was a best guess of what an aeroplane should be. In fact, René Grandjean had built it based on just a single photograph of a Blériot that they had acquired while he was in Egypt a year earlier in 1909. Excited at the prospect of making his own aeroplane, he had returned to Switzerland to begin building. With just that one photo to guide him, Grandjean had pulled off a miracle, reverse engineering and building Switzerland’s first aeroplane. He had done it quite literally from scratch.

On May 10, 1910 — today in aviation history — the pair of men, Switzerland’s first aviators, decided that their “ground testing” was complete. Now it was time to fly. Ernest Failloubaz gripped the controls as the engine was started. It ran up and, as usual, the aeroplane started to roll. As the speed built, Failloubaz experimented with the controls as he always did, but this time, he let the engine run longer. As the plane built speed, it began to grow lighter, bouncing as it did over the grass. Gently, he pulled back on the stick to lift the elevator. The moment of truth had arrived — would the aeroplane fly after all? Even if it did, would he be able to control it? To turn it? To land it? He had confidence, that much was certain — but then again, as a youth of just 17 years old, of course he had confidence. After all, what did he know at that young age of the consequences of failure?

About Ernest Failloubaz

Ernest Failloubaz was an unlikely aviator. He was quite nearly an orphan when at age four, his father died; then at age 10, his mother too passed away. It had all happened quite suddenly. Thereafter, he was raised by his aunt and grandmother, and he worked in the family bakery in the small town of Avenches, Switzerland. Under those circumstances, he grew up quickly. In his early teens, he started tinkering with bicycles. By his mid-teens, he managed to get a motorcycle imported — quite probably, that motorbike was the first to arrive in Switzerland.

Failloubaz taught himself how to ride and soon was motoring around Avenches, with its population of just 1,800, while his grandmother held on, gripping his waist. Decades later, residents would recall the scene of his motorcycle rides. A short while later, he bought an automobile, though the type is lost in history — perhaps it was an early Bugatti some say. Those who recall it remember that he had it painted red, probably so as this was one of the colors of the Swiss flag. Naturally, he taught himself to drive.

A year later, he and René Grandjean decided to build and fly an aeroplane — in France and England, pilots were flying all the time, so they vowed to become the first in their country to fly. To do so, they also decided to build their own aeroplane. It was there that the knowledge and craftsmanship of Grandjean came into play — it was he, more than Failloubaz, who built the plane, but it would be Failloubaz who would fly it.

About Grandjean and his Aeroplane

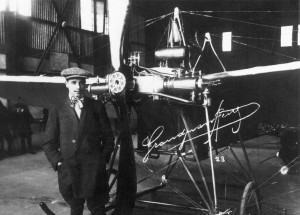

René Grandjean was 24 years old when he left his job as the driver for Omar Pasha Sultan Bey in Egypt and returned to Switzerland to try and build his aeroplane. Born in Bellerive, Switzerland, he did his early schooling Paris before returning to assist his father in the family saw mill business. Early on, he learned the skills of a mechanic, technician and wood craftsman, all of which would be essential later in his aviation career. When he arrived back from Egypt, he met Ernest Failloubaz and the two men built their first plane together, though it was Grandjean who did the lion’s share of the work.

On l’Estivage field in Avenches, they built a hangar. First at Bellerive and later in February 1910 there, day after day, the two men labored on the construction of the aeroplane. Others joined in, including Charles Revelly, the young Gustave Lecoultre, who was the son of a local industrialist in Avenches and, for the metalwork, the blacksmith Bessard Simonet. A mechanic named Vogel joins to assist. Few believe in Grandjean’s vision, even if they help him build the machine. Among them, however, Failloubaz remains confident in Grandjean’s abilities. As the aeroplane nears completion, Grandjean realizes that the best pilot would be the one who weighs the least — the younger Lecoultre would do but has little experience compared to Failloubaz. The decision is made — Failloubaz, the man who taught himself to drive a motorcycle and to drive a car, he will be the one to try.

In October 1909, the aeroplane looked finally completed, but a flaw was discovered in the tail. Failloubaz, despite his youth, offered the solution — applying his knowledge of how bicycles are built. A spoke-like system is designed that supports the weight of the tail. It would be February 1910 before they would begin the first “ground testing” with the melting of the snow. Problems with the landing gear are solved through the help of Gustave Lecoultre. In the following two and a half months, they would learn the handling of the machine on the ground, make adjustments to the engine, a make a few changes to the aeroplane itself based on what they learned driving it back and forth over the grass.

The First Flight in Switzerland

When Ernest Failloubaz took to the field that day on the morning of May 10, 1910, he had already developed some confidence in his abilities. A short hop was all that was planned and Failloubaz felt ready for the task. He hoped just that the aeroplane would make it fully off the ground, fly for a bit, and not land too hard. As it happened, when he lifted off, the aeroplane flew smoothly, though somewhat weakly. Once aloft, he pressed a bit forward a bit to keep it from climbing. He kept it straight for a short while before cutting power and gracefully landing back on the rough field. It was his first landing — flawless.

By lunchtime, it seemed that everyone in Avenches knew of the feat. Word spread quickly over lunch as the two men did nothing to hide their success — nor should they have! Indeed, the English, French and even others from around the world were already taking up flying. It seemed natural too that the Swiss should fly as well. That very afternoon, they returned to fly once again. As before, Failloubaz kept the aeroplane low and flew it straight on for a bit before cutting the power. Once again, he landed it perfectly. As astonishing as it sounds, Failloubaz was a natural pilot seemingly in every respect. Others would later describe that he flew intuitively, making turns and climbs and dives as if he were a bird. He would line up and land with the ease of a practiced aviator.

Grandjean’s Crash

Over the five days that followed the first flight, the two men experimented with Grandjean’s design, Failloubaz always being at the controls. It became apparent to Failloubaz that while the aeroplane flew, it didn’t fly very well. Turns and climbs were not very easy and the underpowered contraption was also a bit overweight — its engine, an ENV, boasted just 40 hp. A different aeroplane would be needed if he were to truly fly. Nonetheless, René Grandjean wanted to fly too — and thus, on the fifth day, he made his first flight. Though he took off, he quickly realized that the difficulties of flight were made to appear all too simple by the natural hand of his friend, Failloubaz. At 25 meters, he pulls back too far on the “broomstick”, their term for the joystick, stalls the plane and noses over into a crash. The aeroplane was damaged, though Grandjean was uninjured despite being thrown from the wreck. It would take some time to fix it, but it would fly again.

In the end, Grandjean’s aeroplane had been a wonderful learning tool — and it was a first for Switzerland — but it quickly outlived its usefulness for Failloubaz, who dreamt of truly flying, turning and soaring through the air. Others soon were learning to fly in Grandjean’s aeroplane — if one can call the short hops it did really flying. The aeroplane served well for a time but then crashed again at the hand of Georges Cailler when it was taken to the Haute Savoie for an air meet in Viry.

More Flights

In the meantime, Ernest Failloubaz traveled to Paris and purchased a Santos-Dumont Demoiselle, which he brought back to Avenches. Daily thereafter, he flew the little plane, learning the art of piloting steadily and perfectly as he flew. In October 1910, the pair and others who had been learning to fly undertook the first air meet in Swiss history — fittingly, it held at l’Estivage. In just five months, Ernest Failloubaz and René Grandjean had started the aviation revolution in Switzerland.

By the summer of 1911, they opened a flight school. Others had come — there were no shortage of students. Other aeroplanes were built or purchased too and soon the field was alive with daily flights as many new pilots took to the air, men like Francois Durafour (who served as the chief flight instructor), Armand Dufaux (whose Dufaux biplanes became a common sight around the field at Avenches), Georges Caille, Paul Beck, Henry Kramer, Louis Gacon, Marcel Pasche, Paul Wyss and Marcel Lugrin. These were the pioneers of Swiss aviation.

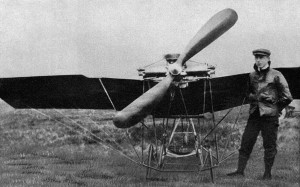

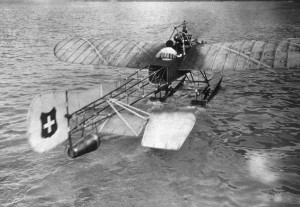

In 1912, Grandjean manufactured his second aeroplane, “No. 2”, which appeared more like an Antoinette in its appearance, though with an arrow fletching of sorts for a tail. It featured a Swiss-built Oerlikon engine with 60 hp. His “No. 3”, built a year later, was a “hydroavion”, a float plane, which he engineered onto twin floats of his own design and soon was attempting flights over the water. Failloubaz would take it out and set several records.

Aftermath

The events started at Avenches by Ernest Failloubaz and René Grandjean would bring Switzerland into the new world of flight. While the men would separate before the start of World War I and rarely afterward collaborate, they remained the grand men who started it all in their country. It is hard to imagine a more unlikely beginning — a dream, a photograph, a project built on hope and little more, and a pilot who taught himself from scratch how to fly. Perhaps it is fitting that this is how aviation began in the country of Switzerland — two men without outside assistance based on talent alone. That is not just their story, but also the story of a nation that prides itself on its independence and ability to innovate, freely and on its own.

One More Bit of Aviation History

In all of his thousands of flights, Ernest Failloubaz only had one mishap — a hard landing at Cheyres when the wind picks up and he is forced to land his Dufaux 5 with Gustave Lecoultre as his passenger. No damage was done. The reason why he was so successful was not just that he was a naturally gifted pilot. He was also meticulous and careful in everything he did. Unlike others who started the engine and simply took off, he would take the time to do a preflight check before each flight — in fact, he may have been the first aviator in history to practice pre-flight checks! His routine was well-practiced and conscientious.

First, he discussed with his mechanic the recent maintenance done, familiarizing himself with what was done and what was fixed, thus giving him knowledge of where problems might lie. Then, he would check the controls, warping the wings, lifting the elevator and testing the rudders. Once satisfied that everything worked properly and freely, he would have the mechanic swing the propeller to start the engine. Even then, he would do a run-up, listening for a time to the sound of the engine at idle and at slight power, hearing any ringing or missing, warming it up. Quite often, he would hear something and shut down the engine; some precautionary maintenance would follow — just to be sure.

Once the engine ran-up well, then he would check the controls a second time before signaling those present that he was ready to fly by turning his cap backwards, putting the bill down his back. With that, he would take off. In all of his flights, based on that routine, he alone among the early aviators had a perfect record.

From the Archives

First Over the Alps — read about Oskar Bider’s incredible flight in a Blériot over the Swiss Alps in a Bleriot XI-b on July 7, 1913.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Whatever happened to Ernest Failloubaz?

Hello

I am always amazed over your knowledge of aviation history. You make the best aviation history pages on the web and beyond.

Kind regards,

Bernhard Kohler

France/The Netherlands

Bernhard —

Thank you for your kind comments! If I could ask for one thing return for all the effort it takes, it would be that you tell your friends about the site. We always seek to grow and expand our readership.

I’m glad you like the site and I look forward to your ongoing support and participation. Thanks again!

Thomas.