Published on June 25, 2013

By Thomas C. Van Hare

By dawn on June 19, 1944, the two opposing carrier groups were positioned with the Japanese to the west and the Americans to the east. To the south of the American carrier group were the Marianas Islands where the Japanese had hundreds of land-based planes. These were given orders to attack. For the Japanese, everything seemed to be working perfectly to plan. Overnight, however, the Americans had sailed south come in range to launch their carrier-based fighters against the land-based attacks that were planned. As the Japanese took off from Guam in multiple raids, American Navy Grumman F6F Hellcats were already overhead to swoop down on the heavily laden bombers even as they were taking off. The slaughter directly over the Japanese airfield was horrific.

It would have continued had not an urgent radio message been transmitted to recall the Hellcats back to the carriers. The fighters were needed because something far more ominous was seen on the radar 150 miles to the west of the American carrier group. The Japanese had gotten the jump on the American fleet and had launched first — and that initial attack wave of 68 planes was already inbound and closing fast. Could this be a reverse of the Battle of Midway and this time, it would be the Americans who were caught by surprise and destroyed?

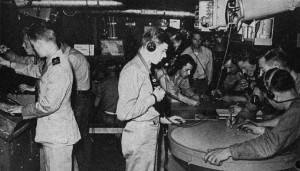

Rise of the CIC

Unbeknownst to the Japanese, however, the American fleet had developed a new technology over the two years since the 1942 Battle of Midway. Whereas the four waves of Japanese planes would have been a surprise just two years earlier, with the American’s latest radars and the new concept of the Combat Information Center (CIC), the Japanese planes were picked up and plotted on tracking boards in all of the key ships of Task Force 58. For the first time, the US Naval commanders had a clear view of the enemy’s location, disposition, altitude, speed and estimated time of arrival. Even a rough estimate of the size of the force could be determined from the intensity of the radar reflection. In a coordinated defense, the different CICs spread across TF 58 coordinated their defenses, launching and combining formations of Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter planes to intercept the incoming Japanese.

The 15 aircraft carriers of Task Force 58 launched literally every Grumman F6F Hellcat they had available to intercept. Yet it looked as if they didn’t have enough time. When first detected at 10:00 am, the Japanese carrier aircraft force was 150 miles out and closing fast — too fast, in fact, for the Hellcats to gain the advantage and intercept the Japanese far enough away to have a crack at defending the Task Force from the attack. The moments were tense as the US Navy fighters gathered and climbed for altitude, speeding west as they formed up. Yet then, the unexpected happened. The Japanese, not knowing that they were already detected and being tracked, suddenly circled and took the time to form up their planes into a better attack organization. For ten minutes, they organized themselves, orbiting at a distance of 70 miles. The first wave of Japanese attackers wanted to be perfectly arrayed to maximize the surprise impact of their attack — instead, however, their careful organization and the delay it caused gave the Hellcats the time to gain altitude and advantage.

What ensued was a massacre. At 10:36 am, the first formations of Hellcats roared into the Japanese attack formation — minutes later, 25 of the 68 planes were shot down. The first wave of defending Hellcats broke off and sped back toward their carriers, ammunition exhausted and fuel running low from the intensive combat. The remaining 43 Japanese planes reformed and continued in, only to be hit by a second series of Hellcats from other carriers in TF 58. Another 16 were shot out of the sky in short order. Just 27 planes remained, some of which were badly damaged. A few forged on and reached the outer picket lines of the vast fleet that was TF 58 — they dropped their bombs on the two destroyers, USS Stockham and USS Yarnall, and missed. Another few attacked the American battleship, USS South Dakota, doing heavy damage, but not sinking her.

Three More Waves

The next three waves were all similarly detected at around 150 miles distance. Each time, the CIC enabled commanders to make decisions, form up defenses and deploy them to intercept the Japanese planes far away from the fleet. Each time a few planes broke through the defensive combat air patrols and managed to attack the Americans. Yet each time, the slaughter was nearly complete, first from the fighters and then from the fleet’s well-prepared AAA fire that had been ordered to General Quarters and stood ready even before the enemy planes came into view.

The Japanese, unprepared for coordinated defensive interceptions that far out, were caught by surprise by superior numbers of Hellcats that attacked, typically from above. Heavily loaded with bombs and, by comparison, only weakly defended by their own Mitsubishi A6M5 Reisen “Zero” fighters, they were shot down in huge numbers. The newer dive bombers and torpedo planes of the Imperial Japanese Navy — the vaunted Yokosuka D4Y Suisei “Comet” (aka “Judy”) dive bomber and the Nakajima B6N Tenzan “Heavenly Mountain” (aka “Jill”) torpedo bomber — were no match for fighter planes, even if they were advanced designs for their attack missions. They were sitting ducks in the sights of the faster, highly maneuverable Hellcats.

Even the A6M5 Reisen “Zero” was no match for the Hellcat, which had been purpose-built by Grumman based on testing done with a captured airframe of the earlier A6M2 and even an A6M5 type — as a result, the Hellcat was faster, could climb more efficiently, dive quicker, turn tighter, and roll more rapidly than the Japanese plane. Further, it was heavier armed and armored. In almost every respect, the Hellcat was superior to the Japanese fighters.

Devastating Results

The results were predictable — in the second wave of 107 aircraft, 70 were shot down. The remaining 37 made it to the fleet and attacked, though flak downed another 27 of their number. The ten surviving planes staggered back to their carriers. The third wave came from the north in what was meant to be a surprise attack from a different direction. Once again, however, the American radars and CIC system took the upper hand and the Japanese were detected and then intercepted far out from the fleet. Yet of the 47 aircraft in that wave, only 7 were downed, with many others damaged. The remainder, however, only attacked piecemeal and did little damage overall — they returned safely to their carriers.

A fourth wave had been launched by the Japanese but failed to find the American fleet. Running low on fuel, they elected to split into two elements — one turned toward Guam to land, refuel and attack again from there, while the other headed for Rota. The group of 18 planes heading toward Rota happened across the American fleet and immediately attacked, simultaneously being set upon by the Hellcats that were launched to intercept. Nine of the Japanese planes were downed before they could reach the key targets — the American aircraft carriers. The remaining nine set upon the two carriers, USS Wasp and the USS Bunker Hill. The intensive defensive AAA from the surrounding ships downed eight of those nine planes that managed to get through. The few that did get to drop their bombs all missed.

As for the second group, which included 49 Japanese planes that were heading for Guam, they were intercepted over the field as they descended for landing — fully 30 of their number were shot down and the rest suffered terrible damage, most being written off after landing. In the midst of the maelstrom of American bullets and attacks, one of the pilots in a Hellcat from the Lexington was heard to comment over the radio, “Hell, this is like an old-time turkey shoot!” — it would be a phrase that forever after would be associated with the battle, which became known as the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.

Aftermath of Day One

By days end, the Japanese carrier fleet had lost most of its aircraft. Further, soon after the attacking planes were launched, two of the Japanese aircraft carriers had come under attack by the US Navy submarines USS Albacore and USS Cavalla. USS Albacore torpedoed Vice Admiral Ozawa Jisaburo’s flagship aircraft carrier, the Taiho, managing a single hit, though damage appeared manageable. USS Cavalla had hit the aircraft carrier Shokaku, scoring three catastrophic hits with torpedoes. The carrier was mortally damaged and did not remain afloat for long — 1,263 men were unable to abandon ship before it rolled over and sank beneath the waves. As mistakes were made in damage control on the Taiho, it too later succumbed.

For the Japanese, it was a stunning defeat. For Vice Admiral Ozawa Jisaburo, the day had started on a positive note — the Japanese had managed every advantage. They had detected the Americans first, launched four waves first and ordered an attack from their vastly superior land-based air force. Yet everything they had launched had been intercepted, decimated and stopped. Just one American ship, USS South Dakota, had suffered a serious hit — and it remained afloat and underway.

However, the worst was yet to come.