Published on August 9, 2013

By Thomas Van Hare

As it happened, of the ten pilots who made a showing to start the Circuit de l’Est from Issy, near Paris, just six would make it off successfully. First to go was to have been Hubert Latham in his Antoinette, an older design of the plane. He didn’t get off on schedule, however, and it was Emile Aubrun who made it out and pointed his Blériot toward Troyes, 135 kilometers distant. The early hour of the day — the white start flag had gone up at 5:00 am — didn’t reduce the crowds who stood along the boundaries of the field to watch. Soon after the others attempted to make it off and most did, though a few failed in the attempt.

What should have been a 90-minute flight to Troyes over a distance of 140 kilometers was longer than that for most. Hubert Latham had dropped out as he soon discovered his older Antoinette was not up to the task — indeed, he could not successfully clear Issy. The Peruvian Bielovucic also had failed to successfully complete the first leg in his Voisin — he managed a take-off after engine trouble, but the repairs made were insufficient and he had to return to immediately land at Issy. Two other pilots who were late registrants, Guillaume Busson on a Blériot and Henri Brégi on a Voisin, also took off, though neither could complete the trip to Troyes.

It was not an auspicious beginning for the race.

High Attrition Rates

Alfred Leblanc and Emile Aubrun flew the route in just over an hour and a half each, arriving just five minutes apart with Leblanc in the lead. Incredibly, Leblanc had gotten lost and had wandered off course for 20 minutes before recovering his position after recognizing the church spire at Mourmont. He continued on to Troyes and still bested Aubrun, the second to arrive, by slightly more than five minutes. That had been possible because Aubrun had avoided a straight course and instead followed the Seine to Troyes to ensure that he didn’t get lost. The German pilot, Otto Lindpaintner, required nearly two and a half hours, while Georges Legagneux made it in just under four hours. Both had stopped en route. C. T. Weymann was an hour later than that, followed twelve minutes later by Julien Mamet.

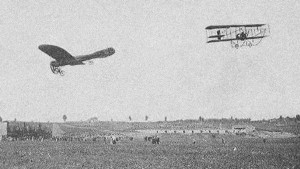

As the pilots would soon learn, both Busson and Brégi had crashed en route, with Busson coming down at Naugis, having wrecked his aircraft. Brégi had had motor trouble and managed a successful forced landing at Pontecarré. Of the six who made it to Troyes, however, only three would make it on the next leg on from there to Nancy. These men were Leblanc, Aubrun, and Legagneux, with the latter flying a Henri Farman biplane while the other two forged on in the reliable and faster Blériot XIs. All of the top three contenders were Gnome-powered. These three men alone would continue on, competing as well at Nancy and at the other stops for the daily prizes of highest altitude, shortest take-off distance, and most passengers carried, among other locally sponsored competitions.

As the cities ticked by, day after day, the three pilots managed each leg more or less successfully. Usually, Leblanc made it in first. Legagneux failed to complete one of the legs in the required time, but arrived the following day. Along the way, the competitions were soon realized to put more stress on the aeroplanes and pilots, risking the bigger prize of the completion of the event. Luckily for the crowds, other pilots in the local areas joined in to compete for those prizes as well, which added to the interest in the event.

Among the various public relations gambits and competitions that took place along the way, one other is particularly worthy of note. On departing Douai en route to Amiens, Leblanc, Aubrun, and Legagneux were challenged in a race against 47 carrier pigeons, since the pigeons could fly nearly as fast — and sometimes faster — than an aeroplane. As Leblanc took off, the carrier pigeons were simultaneously released (luckily, he did not hit any of the birds) and the race was on. Leblanc was easily making 70 km/hr, however, and he outdistanced most of the birds, as did Aubrun and Legagneux, though neither of the latter two could beat the fastest bird, which arrived just six minutes behind Leblanc! Legagneux, the last in with a time of just over 90 minutes, beat the final bird by 12 minutes.

The Final Leg and Moisant’s Departure

In the end, as the remaining flyers left Amiens on the last leg of the Circuit de l’Est — eight attempted to take off, including the escort pilots — Leblanc was first off given his position as the competition’s leader. He was followed by Lieut. Letheux, in his role as escort (not competitor), yet failed to lift off. Aubrun took off next, followed by Legagneux. Three more of the escorting military flyers then attempted to take off but also failed. In effect, the escort arranged had all failed to make it off.

Amidst the festivities of the final departure, another pilot who had not completed any of the previous legs, John Moisant, an American architect and pilot (of Spanish ancestry), took off, carrying his mechanic in the aeroplane (a two-seat Blériot). Rather than steer toward Issy, instead the crowd observed that he headed northwest toward the coast. Later, it would be realized that he had flown across the Channel to England, a flight that put him more in the history books than completing his last leg of the Circuit de l’Est, having made the first crossing in aviation history with a passenger on board.

As it happened, John Moisant and his mechanic, M. Fileux, had achieved an unexpected press relations coup of being the first pilot in history to fly a passenger across the English Channel. His flight even upstaged the press coverage of the Circuit de l’Est, though both events were public relations successes. Though it took Moisant and Fileux just a few hours to cross the Channel, what followed was a nearly week-long trial of short flights within England that battled winds, navigational errors (he knew nothing of the topography of England), and various crashes before finally, he reached his destination of London. On the last leg of the trip, he carried a stray kitten he had found along with him in the cockpit of his Blériot, the cat protected and kept in a basket on his lap.

The Race End

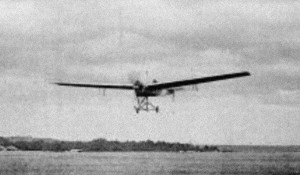

From the dawn’s first light at Issy, a massive crowd formed to welcome the racers on their final flight. Estimates put the numbers at 250,000, though few could do an accurate count. Most had arrived in the hours just after sunrise and waited until the first of the flyers arrived. As well, far away at the Eiffel Tower, crowds lined the various levels to catch a glimpse of the distant aviators as they made their arrival. Lieut. Lucca in his Wright machine made the first showing, though he wasn’t a competitor, but rather one of the pilots of a military escort plane that had covered an earlier leg. He had flown in from Satory where he had spent the night, hoping to arrive in time to meet the victorious pilots and celebrate with them. A large military and official delegation greeted him, led by General Brun of the French Army.

Next in was the first of the competitors. Predictably, it was Alfred Leblanc in his Blériot. His plane sputtered into view, securing the victory amidst triumphant shouts and cheers from the assembled crowds and soon he landed on the field. As Leblanc climbed out of the Blériot, he was lifted and carried along with the surging crowd to the front of the grandstands where General Brun extended his most heartfelt welcome. The assembled dignitaries of Paris were on hand. Soon after, Emile Aubrun arrived in his Blériot to take second place in the competition. Lieut. Cammerman had finally gotten off and he arrived hours later, followed by Legagneux, who had taken about 5.7 hours to make the journey with several stops along the way.

Final Status of the Others

None of the other aviators made it to Issy for the final celebration. Indeed, the three pilots who made it had been the very ones who had made almost every leg successfully. Of those, only Leblanc and Aubrun had completed all of the circuit, flying the full 805 kilometers distance. Leblanc had done it in 12 hours, 1 minute, 1 second, while Aubrun had managed the flight in 13 hours, 31 minutes and 9 seconds. Legagneux had only completed four stages of the course, managing 510 kilometers in 17 hours, 21 minutes, and 13.5 seconds. Of the other three pilots who had completed the first stage from Paris to Troyes at the beginning — these being Lindpaintner, Weymann, and Mamet — none had made it past Troyes.

The course of the Circuit de l’Est, what would be today a Sunday full-day trip for a modern private pilot, had proved to be a ten-day, grueling experience. Alfred Leblanc had come away with 100,000 francs in prize money from Le Matin (about 4,000 pounds sterling in those days, which equates to about 350,000 pounds sterling; in today’s buying terms, that would be 406,000 euros or $542,000 USD). In other words, Leblanc had become a rather rich man as a result of a single competition. In addition, the aviators took away prize money from the afternoon competitions at each of the cities they visited — and in some cases, other local aviators, such as Paul de Lesseps and Henri Brégi (in his Voisin) joined in to compete, even if they hadn’t completed any of the full legs of the Circuit itself on any of the days within the times allotted. Leblanc and Legagneux were the biggest winners, taking home 27,000 francs each from the local competitions.

In retrospect, the prizes offered by Le Matin, the Daily Mail, Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe, and the others were staggeringly large. They were enough, one could say, to bring the aviators of the day to the starting line to risk their lives for the advance of aviation and aeronautics. Thankfully, none of the competitors in the Circuit de l’Est died as a result of the competition, though of the 35 who pledged to start, just two managed the whole circuit. The vast majority of those who tried to compete were unable to even make the flight to Issy-les-Moulineaux to start the race.

That the Circuit de l’Est is relatively unknown today in popular history is surprising — it was an exemplary competition and one of the first real cross-country events in aviation history. The men who flew it were some of the greatest names of the day, real pioneers who risked their lives to advance the art of aviation. We owe them a debt of gratitude today for their work, though we also can know that for many of them, they made a good living for themselves, as they did with many of the competitions they attempted, so long as they survived to fly again another day.

Do you have information on Troyes 1910 Vignette stamps?