On November 13, 1918, the pilots of the German fighter group, Kampfeinsitzerstaffel 5 (Kest 5), flew their final mission of the Great War. Two days earlier, at the 11th Hour of the 11th Day of the 11th Month of 1918, the Armistice had been signed. The war was over and many Germans were dismayed at their country’s loss.

The Kest 5 pilots were ordered to pull back from the front lines to avoid any unintended contact with Allied forces. Their planes were then to be turned over to the French as war prizes. Upset with the terms of the surrender, they flew instead to Switzerland. It seemed like a good idea at the time, but nothing went quite as planned.

The Intended Order

The pilots were ordered to fly from their front line base at Lahr-Dinglingen Airfield in western Baden-Württemberg, to Friedrichshafen, located adjacent to Lake Constance. This was 75 miles to the southeast. Once at Friedrichshafen, they were to park their planes. Most likely, their planes, new model Siemens-Schuckert D. IIIs, among others, would be destroyed or perhaps paraded around by the French in victory celebrations.

Many German pilots, including the German ace, Vizefeldwebel Fritz Beckhardt, were angry at the order. Rather than complying, Beckhardt and some of the other pilots of Kest 5 chose to fly instead to neutral Switzerland. They hoped for a positive welcome and the chance to turn over their planes to the Swiss, who they imagined would be grateful.

Fritz Beckhardt’s personal plane was a Siemens-Schuckert D. III. The type was one of Germany’s best fighter aircraft. The other leading pilots from Kest 5 intending to fly to Switzerland were Feldwebel Hans Weisbach, who, along with Vizefeldwebel Ernst Brantin, would fly together in a D.F.W.L. two-seater; Leutnant Gustav Michels, who would fly across in an Albatros A.W.S. D.5a; and both Oberleutnant Heinrich Dembowsky (the commander of Kest 5) and Offiziersaspirant Arnold Eger, who would each fly across the border in their personal Siemens-Schuckert fighter plane.

What the pilots of Kest 5 didn’t know was that the Swiss would answer their arrival with gunfire.

The Final Mission

When dawn broke on November 13, the five planes of Kest 5 were fueled and readied for departure. The pilots strapped themselves into their machines and in a cloud of blue-grey oil smoke, the engines came to life. Beckhardt allowed his machine time to warm up before he advanced his throttle to take off. His plane accelerated quickly across the low cut grass of the airfield and then he was climbing upward into the morning sunlight. He made a final turn around the airfield before heading southeast in the general direction of Friedrichshafen.

We cannot know with certainty Beckhardt’s exact course that day. It appears he flew until he first saw the shore of Lake Constance in the distance. Then he veered south to trace a course toward Lake Zurich in Switzerland. His plan apparently was to find a suitable landing field somewhere along the Swiss lake’s edge. Flying separately, Oberleutnant Dembowsky and Offiziersaspirant Eger took a direct route. They flew toward the closest border with Switzerland. Two other pilots flew the same route as Beckhardt. One flew on his wing. It took less than an hour before all of the planes were across the border and into Switzerland.

Who was Fritz Beckhardt?

At the end of the war, Vizefeldwebel Fritz Beckhardt was one of Germany’s leading aces. He had 17 confirmed kills to his credit, though his personal count of kills was more than 20 shot down. Beckhardt was also a Jewish-German pilot. Although many in Germany had questioned whether Jews had the courage to fight, Beckhardt had proved them wrong. Proud of his heritage, he was a member in the League of Jewish Soldiers at the Front.

Twice he had met and received personal congratulations from the German Emperor, Wilhelm II, for his victories. Among his many citations, he wore the Iron Cross Second Class. He was also one of only eighteen men in the entire German military to have been decorated with the House Order of Hohenzollern. A friend and fellow German-Jewish pilot, Edmund Nathanael, had received that high citation as well.

Fritz Beckhardt had come from humble beginnings. Before the war, he had been simply a grocer in the family store. When the war began, like many others, he had answered the call to arms and joined the German army. At the front, he demonstrated extraordinary bravery first in infantry combat, earning him Iron Cross Second Class. In 1917, perhaps tired of combat in the mud, he requested the opportunity to train as a pilot. This was approved and he quickly earned his wings. He was subsequently assigned to fly reconnaissance aircraft. Displeased with the idea of not being able to fight, it wasn’t long before he requested to fly fighters. Once again, he was approved for advanced fighter training.

He joined a combat fighter unit in February 1918. Just nine months remained before the war ended, however, and the so-called “glory days” of Germany’s dominance in the skies had ended. Nonetheless, he made short work of the enemy and shot down 17 aircraft in the ensuing months. During that time, he flew with many of Germany’s other great aces, including Hermann Göring.

A Jewish Pilot with a Swastika

In the air, Beckhardt’s personal symbol was the swastika, which was painted on both sides and on the top of his fighter plane’s all-black fuselage. That a Jewish pilot would adopt the swastika as a symbol was not out of place at the time. During World War I, the swastika was just another well-recognized good luck symbol that pilots on both sides used. It was only after the end of World War I that a number of nationalist parties in Germany, chiefly the Nazis, adopted the swastika and perverted its meaning into a symbol of racial purity.

Beckhardt’s swastika was backwards from the later Nazi version, with the crossbars pointed counter-clockwise. His bold swastika was large and clearly visible on the plane’s fuselage. He hoped that the symbol was recognized and would instill fear in the French pilots as his reputation grew and they would recognize his markings. They would know that an ace was among them in the skies, hunting for yet another kill.

Arrival in Switzerland

On that morning of November 13, however, Beckhardt’s least concern was combat with the French. With the war over, he could fly calmly without scanning the skies for enemy planes. He was at ease with himself and his decision to take his plane to Switzerland. After Beckhardt crossed in Swiss territory, he flew directly south toward Lake Zurich. There, he hoped to find an excellent landing spot along water’s edge. He did not expect to find any airfields because the Swiss did not have an active air force and most Swiss pilots trained in France. As it was, he and the other plane that was flying on his wing — the two-seater with Oberleutnant Dembowsky and Offiziersaspirant Eger on board — found the town of Rapperswil on the shores of Lake Zurich.

The two descended and made a wide turn over the town, flying past the church spire and castle that stood next to the lake. Many Swiss residents ran outside upon hearing the sound of the aircraft engines — so rare was a plane in the skies over Switzerland that any flight always aroused great excitement. That day in Rapperswil, people were shouting, “En Flüger, en Flüger…” as the planes flew overhead. Expecting to see the Swiss national insignia on the wings, instead the people were stunned to recognize German crosses. Almost immediately, a Swiss army unit that was billeted next to Rapperswil opened fire. The sound of gunfire echoed through the town.

In the air, Feldwebel Weisbach and Vizefeldwebel Brantin in their two-seater turned away as the bullets whizzed past. They flew to the east and then dove toward the lake’s edge. Once beyond the town and out of the line of fire, they spotted a monastery. This was Wurmsbach, located just outside of Rapperswil. They put their plane down in the fields alongside, shut down the engine, and climbed out. They were pleased to have gotten down in one piece after all of the gunfire they had encountered over the town.

Fritz Beckhardt, however seemed completely unperturbed by the gunfire. Perhaps he recognized that the Swiss weren’t properly leading their fire or shooting accurately. Perhaps he had seen worse in the skies over France. As it happened, he flew directly over the armory where the Swiss forces were located. Rather than turn away to the east as Dembowsky had done, Beckhardt simply flew on. He dipped the nose of his Siemens-Schuckert toward the city hall, cut the engine, and landed not far from Gemüsebrücke in the damp grass of a meadow. Three stunned lads looked on, each with a wagon in tow. They were rooted in place at the sight of the plane.

After Beckhardt landed, he waved frantically to the three boys to come over. They were less than 100 yards away, still standing stock still. After some discussion between them, the three abandoned their wagons and jogged over. Beckhardt climbed out of the cockpit and breathed in the clear air. In the wing, he spotted a fist-sized hole — the results of the ground fire. Had it been a few feet over, the bullets might have hit his engine or even him. One of the boys would later recall how the flyer wore his leather flying helmet and how its ear flaps dangled down. The boy also remember that Beckhardt had sported a high-necked leather jacket with fur lining. His collar turned up in a style reminiscent of Manfred von Richthofen.

To nobody in particular, Beckhardt simply said, “Griis Gott”. Then he lit a cigarette, probably to calm his nerves. It had been an unexpectedly risky day. Shortly thereafter, the Swiss army arrived and took him into custody.

Aftermath and the Fate of the Others

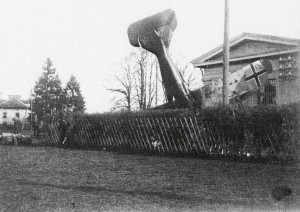

Leutnant Michels, flying his Albatros A.W.S. D.5a, also came down at Rapperswil safely. As for Oberleutnant Dembowsky and Offiziersaspirant Eger, their plan to fly just inside the Swiss border and land proved troublesome. As it happened, closer to the German border, the Swiss gunners were better shots. One of the planes was damaged and overturned when it crash landed, shattering its propeller as it flipped. It came to rest with the tail high up in the air. The pilot was uninjured. The other one landed safely.

After capture, the pilots were gathered together at Rapperswil. In the days that followed, the famous Swiss aviator Oskar Bider, then a Oberleutnant with the new Swiss Air Force, came down to meet with them. The newspapers carried articles talking about the German pilots and their planes. Less than a week later, following the news of the safe arrival (albeit with gunfire) of those first planes, another 12 pilots made their way to Switzerland. They arrived on November 17 and 18.

The question of what to do with the German planes was solved quickly. The Swiss simply pressed the new German machines into their new air force, over-painting the tail marking and fuselage insignia with Swiss crosses. The damaged aircraft were kept too and later cannibalized for parts to keep the others flying. Two years later, the remaining planes were sent back to Germany for modification and rebuilding, and when this was completed they were returned to service in Switzerland. By then, Switzerland had also acquired many newer French types, such as the Nieuport 21. Over the weeks following their arrival, the German pilots were repatriated to Germany.

With the arrival of the pilots from Kest 5, the Swiss Air Force made a huge step forward. Though it had been founded four years earlier in 1914, by the end of World War I, Switzerland had just nine pilots and a handful of outdated airplanes. With the new Siemens-Schuckert D. IIIs and the Albatros A.W.S. D.5a, they were able to modernize their air force.

Today, the Swiss present a modern, powerful air force that is well able to patrol and defend the country’s airspace. From their small start in 1914 and with the huge advance that they took at the end of 1918, they have come a long way.

As for Fritz Beckhardt, with the rise of the Nazis in Germany, he worked to help Jews escape Germany. He was discovered and imprisoned but later pardoned by another former WWI fighter pilot — Göring himself. Knowing that they would only be free for a short while if they remained, Fritz Beckhardt and his wife left Germany and drove in their Adler (the family car) to Lisbon, Portugal. Then, after months of waiting and petitioning, in May 1941, the RAF picked up the two and flew them to Bristol, England. They were interned for a short while but then released. Thereafter, they lived in London, England, having escaped death at the hands of the Nazis.

One More Bit of Aviation Trivia

That the Jewish ace, Fritz Beckhardt, had the swastika painted on the sides and top of his fuselage is viewed as an historical anomaly, but is not to be unexpected given that at the time, the swastika was simply a good luck symbol. Interestingly, there was little confusion as to the meaning of a Star of David, which was seen universally as a symbol of Judaism. While none of the Jewish flyers had Stars of David on their aircraft, one German pilot, Ltn.d.R. Adolf Auer, of Jasta 40, had exactly that — and he wasn’t even Jewish!

Post Note: There is some possibility that the story of Fritz Beckhardt and Leutnant Michels are reversed, though a reasoned assessment of the stories and records points to the above being the likely most accurate representation of what happened that day.

Very interesting story! Keep up the good work! With interest I read all your newsletters and stories. Thanks again!

In 1936, he drove two Jewish brothers named Frohwein to the Belgian border so they could flee the Gestapo. The Frohweins later opened a kosher butchery in Golders Green, London. In 1937, Beckhardt was accused of having sexual relations with a non-Jewish “Aryan” woman. As a result of the trial on 14 December 1937, he was convicted and sent to prison for a year and nine months. After his time in prison, he was taken in protective custody to a penal company in Buchenwald concentration camp as prisoner no. 8135. Upon his release in March 1940, it was written in his records by the SS that he had scored 17 victories as a fighter pilot during World War I.