Published on May 7, 2017

By Thomas Van Hare

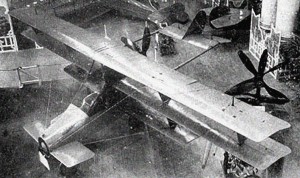

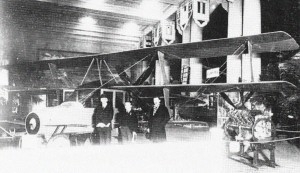

“At the aero show held at New York early this year there was exhibited a Curtiss triplane, which aroused the greatest interest owing to the decidedly novel lines on which it was constructed. The Curtiss Autoplane as it was called was really a motor car with wings.” So began the description in the Royal Aero Club’s magazine, Flight. This was the world’s first “roadable plane”, as they are known nowadays — the aeronautical dream of combining a car with an airplane. It happened 100 years ago in 1917.

Even if the idea of a flying car is a century old, no manufacturer has yet made it practical. The attraction is obvious — having flown hundreds of miles, the aviator finds herself in a distant town. Airports, however, are almost always well outside of the city limits. How to get downtown for the proverbial “$100 hamburger”? Aircraft designers have long dreamed of landing, taxiing in, and then dropping off the wings, to transform the fuselage into an automobile. With that, you drive downtown for a bit of shopping, lunch, or perhaps a business meeting.

What sounds good as an idea, however, doesn’t work out in practice. Cars are not held to the same regulatory standards as airplanes and making the two compatible is deeply challenging. Airplanes must be exceedingly lightweight, while cars must be made stronger to keep the passengers safe from possible accidents on the road. Cars are designed to travel on four wheels for tens of thousands of miles, while airplane wheels and landing gear only require high speed touchdowns; the tires themselves are replaced after a few hundred landings because they wear out fast. The drive system to power a propeller does not easily convert into a system to turn the tires and accelerate the car along without a lot of gearing and added weight. The aerodynamics of the two are vastly different — even the speeds that they are expected to travel require different angles, fairings, and contours.

One hundred years ago, the Royal Aero Club’s magazine, Flight, implicitly recognized these issues. The regulatory free zone that prevailed in 1917 was less a challenge, however, and many saw the merit in the idea. The writers related the public suspicion with which the design was viewed, saying, “…although there were those who, at the time of the show, were inclined to smile and regard the machine as something of a joke on the part of the Curtiss firm, or at most a machine built solely for the purpose of creating a sensation at shows and in processions, a brief consideration will suffice to show that the machine, in spite of unconventional design, is not the freak aerodynamically some critics suggest.”

At least Flight respected the effort and went to great lengths to detail the key design features: “The engine, a 1oo h.p. Curtiss, is mounted in front under a bonnet, motor car fashion, and is provided with the ordinary starting handle projecting through the radiator in the nose. A four wheeled under carriage is fitted, the front wheels of which are connected up to the controls in such a manner as to allow of steering the machine on the ground at low speeds. Inside the limousine body are three seats, the pilot’s in front, and two passenger seats side by side further back. The upper plane is attached to a cabane resting on the roof of the body, while the two lower planes, the bottom one of which is of shorter span than the other two, are attached to the body. The propeller is mounted approximately on a level with the centre wing, and is driven through a long shaft from the engine. In addition to the rear elevator which, with the other tail units, is mounted on two booms, there is a small front elevator projecting out from the engine bonnet, giving the impression of mud guards.”

Indeed, while the design sounded promising as written, the key issue proved to be aerodynamics. Just how to achieve efficiency when the fuselage, rather than being a narrow and arrow-shaped balancing act, to which attached the wings, the engine and the tail, was a wide, four-wheeled car?

To answer that question, Flight continued with its report: “At first sight it would appear that the head resistance would be somewhat excessive, but owing to the shape of the body, a section through a plane on level with the bottom of the windows would approximate very closely to a stream line section, so that the real resistance may probably be found to be a good deal less than one would at first expect. Placed where it is, the propeller should coincide pretty well with the centre of resistance, as it must be remembered that the upper wing carries a greater load than the other two, and that, although the resistance of the body is acting fairly low down, the bottom plane is of short span and offers but little resistance.”

The overriding sense one has when reading the article is that the writers felt that even the greatest aerodynamic challenges could be overcome. Common sense, thoughtful design, and careful fairing would reduce wind resistance and make the design aerodynamically sound. The use of a pusher propeller helped increase the efficiency of lift generation from the wing.

Lacking flight test data or the opportunity to fly the machine themselves, the writers at Flight reverted to comparison to tease out further issues: “The machine would have a very low centre of gravity, certainly, but this has not proved detrimental to good flying in such machines as the Morane parasol, and the centre of side area also appears to be quite low in comparison with the centre of lift of the three wings. A constructional feature which could, we think, be improved upon is the method of mounting the tail planes, which does not impress one as being any too strong. Otherwise the machine appears to us to promise very well in many respects, and the Curtiss firm are to be congratulated on being first to produce what really seems to be the first attempt at the comfortable enclosed small machine of the future.”

The answers that the Curtiss representatives themselves gave at the show when asked, however, were less than compelling. As a result, the reporters from Flight struggled to remain optimistic given the lack of flight date. They believed in the overall promise of a flying car, but left the show uncertain if the machine had even flown at all: “At the moment we have not been able to ascertain whether or not the machine has been flown, but although alterations and improvements are still to be expected, it does appear to us that this machine is a step in the right direction. For a three seater the power does not impress one as being quite sufficient, but it should not be a matter of great difficulty to install a more powerful engine, if that should be found advisable, which we fancy will be the case.”

The article ended, “To be concluded.”

Likewise, the New York Times covered the Exposition and urged its readers to get to the show before closing. Fancifully, they called the Autoplane, the “Curtiss Aerial Limousine”. Their reporting called the design the talk of the entire show: “More wonderful than the Rodman Wanamaker Flying Boat “AMERICA”, more interesting than the huge military planes is this unique and novel product of the inventive genius of Glenn H. Curtiss, — The Curtiss ‘Aerial Limousine.’ Since its unveiling on Thursday night at the Aero Show it has been the talk of New York. Epoch making in its conception and design, this wonderful aeroplane is a veritable drawing room on wings, a modern magic couch which can actually whisk you away with the speed of the wind. We urge you to see it before the Show closes next Thursday.”

As it happened, despite best hopes of Flight and breathless reporting of the New York Times, the Curtiss Autoplane never flew. It did lift off the ground for short distances in testing, but apparently never made it out of ground effect. True flight proved impossible. More power was needed given the weight and poor aerodynamics of the fuselage and limited wing area. Even stacked three-high as a tri-plane design, the wings proved insufficient in lift, even if they were a design borrowed from the proven Curtiss Model L trainer. A reliable Curtiss OXX water-cooled V8 engine was employed — boasting 100 hp. This proved insufficient to get the Autoplane going fast enough to fly.

The further design work that the writers at Flight hoped would result never happened either. A couple of months after the Pan-American Aeronautical Exposition, where the design was first exhibited, the United States entered the Great War in Europe — this was World War I. Suddenly the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Co. found themselves busy with work from the US Army. They abandoned the effort to produce the Autoplane and proceeded with design work on what would become the company’s signature airplane — the Curtiss Jenny.

Nonetheless, at the time of the aeronautical show where the Autoplane was first exhibited, Glenn Curtiss filed a patent covering the design. Fifteen separate claims were made, each an individual innovation of its own right, and when combined together, it claimed the invention of the combination of the airplane and car for all time. The patent, filed on February 14, 1917, was awarded slightly more than two years later on February 18, 1919, entitled, “Autoplane. US 1294413 A”.

Today, the idea of the “Flying Car” is again seen as part of a promising future that will free mankind from rush hour traffic. Rather than a conventional airplane-like design, however, the future appears to be more a quadcopter or other helicopter design. Perhaps the biggest challenge impeding the future of “Flying Cars”, however, won’t be technology, but rather piloting skill. On the other hand, with driverless cars and trucks now becoming the norm, is it all that unlikely that the pilotless “Flying Car” is that far in the future?

One promising design (pictured above) is the EHang 184, made not by airplane firm or an auto company, but by a proven radio-controlled model drone company. EHang describes their deisgn in a press release from January 2015 as, “the world’s first electric, personal Autonomous Aerial Vehicle (AAV) that will achieve humanity’s long-standing dream of easy, everyday flight for short-to-medium distances.”

Yes, that’s right — electric. Gasoline-powered engines, after all, are so 20th Century. If he were alive today, Glenn Curtiss would be amazed, perhaps even as much as we are.

Whether UAV or AAV, the Ehang design does not approach the definition of a flying car, so I’m not sure why you chose to include it as having any straight-line relevance to this article. It’s a fascinating craft, yes; but, a flying car prototype, no.

Unless, you fold up the props and can somehow manage to load it onto a pickup truck, to head into town for that $100 burger.

Sir,

I am a Automotive Historian.

Have a neat picture of a early racing plane, raced at SCCA sponsored base races.

This on was Indiana I believe.

Also, do you know any history about a very early pilot;

DALLAS SPEAR.

Hope I am spelling his name correctly.

John 217-734-9400