Published on June 6, 2017

By Thomas Van Hare

On D-Day, June 6, 1944, after passing a tense and confusing early morning hours in the cockpit of his yellow-nosed Messerschmitt Bf 109G, Leutnant Thomas Beike of Jagdabschnittführer 5 received his mission orders. With two other Bf 109Gs, he was to fly a fast reconnaissance flight over Normandy Beach to assess and report what was happening. With the engine started, he pushed the throttle forward and rolled out of the hidden, tree-lined revetment north of the French town of Évreux, then he took off into a sky filled with Allied aircraft.

Even as his wheels came up, the first P-51D Mustangs were already coming down to attack. He had his orders, however, and rather than engage them in a dogfight, he turned away to escape. One of the other two Messerschmitts was hit, however, but at full power, he pulled away, all alone. The D-Day beaches were straight ahead. This is his story.

WATCH THE VIDEO!

Most know of the famous flight of Josef Priller and his wingman, a single pair of Luftwaffe Fw 190A-8 fighters that flew down the D-Day beaches and returned to report what they had seen. For many years, that flight was supposedly the only sign of the Luftwaffe in the air during all of D-Day. Decades of research, however, have proved that wrong — and new evidence has emerged that multiple others flew as well. Nonetheless, the Luftwaffe was so outnumbered that it could do little to stop the invasion.

A Newly Discovered Daring Flight

New information about another daring flight on D-Day comes from a book of interviews that was undertaken with surviving German soldiers, all of whom were veterans of D-Day. These men were located in 1954 and interviewed by Dieter Eckhertz, a former German war correspondent who during WWII wrote stories for the German military propaganda magazines, “Signal” and “Die Wehrmacht”. Just a few months prior to D-Day, Dieter Eckhertz had toured the Atlantic Wall and written reports for those magazines. Ten years later, on his own personal initiative, he searched out survivors of some of the German units he had visited during the war to conduct his interviews.

His notes and the transcripts of the interviews were then put into storage and left untouched for over 70 years. Perhaps Herr Eckhertz knew that someday his efforts would serve to document the other side of the story of D-Day. Perhaps he simply did his interviews and research to satisfy his own interest. Nonetheless, his interviews uncovered stories that would have otherwise never been told. It is true, in a sense, that history is written by the victors — few Germans wanted to talk about their experiences after the war ended. As it happened, Dieter Eckhertz’s grandson, Holger Eckhertz, discovered the box of interview notes and transcripts. In 2014, he published the first of them in a book called D-Day Through German Eyes. Subsequently, in 2015, given the positive reception of the first book, he published a second book of interviews.

Among the interviews in the second book is an incredible story of Leutnant Thomas Beike of Jagdabschnittführer 5, who was based at a hidden airfield “somewhere north of Évreux”. He revealed that he had flown over the beaches of Normandy on D-Day. The Luftwaffe ace Josef Priller, it seems, wasn’t the only Luftwaffe fighter pilot to race down the beaches at low level after all.

Experiences Leading Up to D-Day

Thomas Beike’s flight originated from one of the hidden satellite airfields at Évreux, a small French town in Normandy, south of Rouen. Évreux is only 90 km east-southeast of the invasion beaches. During WWII, the Luftwaffe had used the field and the surrounding area as a series of airbases, as well as a decoy airfield designed to draw off Allied bombing raids. On D-Day, the area was the base of both Jagdabschnittführer 5, Schnellkampfgeschwader 10, KG-54 (and possibly several other Luftwaffe units). This was in the area that the Germans called the Évreux-Lisieux Sector.

Prior to D-Day, Jagdabschnittführer 5 had been based on the flat fields north of the town, on the grounds of a chateau that the Luftwaffe had taken over for use to house the pilots and ground crews. The Luftwaffe provided well for its units in France, in stark contrast to the challenging conditions on the Eastern Front, where Leutnant Thomas Beike had previously been posted. As he noted in his interview, “I went from bedding down in a frozen hut, as I did in my posting on the Eastern Front, to sleeping in a proper bed with a staff servant to attend to meals and the polishing of boots and other necessities.”

He went on to note that the chateau “had a wine cellar which was very well stocked, and the quality of food available locally was remarkable.” As well, he spoke freely about the pilots “were popular fellows with the French ladies”. Life at the airfield was excellent indeed and many of the French supported the Germans willingly with food and other support that supplanted the rations that the Luftwaffe offered the squadrons on the front.

In the months prior to D-Day, as the number of bombing raids increased, a decoy airfield was built nearby in hopes of distracting the Allied air attacks from the Luftwaffe’s forward-positioned aircraft. The months of living well in the chateau too came to an end as the building was too easy a target. Soon, they were moved and billeted off the field in a farm house several kilometers away. The planes, once parked around the airfield, were moved into the forest and hidden in reinforced revetments, surrounded by thick blast walls. On many mornings, in the early hours, the squadron’s planes would launch in hopes of intercepting returning RAF night bombers as they crossed the coastline heading home to England. They shot many down in this way.

A Birthday Celebration

On the night of June 5, six of the pilots and two senior base officers gathered for a small birthday party of one of their number. A number of French ladies joined them, along with the wife of one of the senior officers, who was visiting — an ill-timed trip to see her husband if ever there was one. Bottles of wine were opened and the small celebration was well underway when the sounds of the vast force of C-47s passing overhead interrupted what otherwise might have been a late night. The group went outside and listened as the vast armada was passing, the droning of the engines sounding markedly different from German engines which, in multiengine aircraft were not usually adjusted to synchronize their propellers. Thus, while the German planes made a rising and falling sound as the propellers rotated at slightly different rates, Allied planes sounded a consistent, synchronized tone.

Soon the ladies departed and were driven home by a squadron car. The pilots made efforts to sleep, knowing by the sound of the vast armada that the big day had come. As for Leutnant Thomas Beike, he slept uneasily, continuously awakened by the sounds of Flak guns, the droning of the aircraft engines and the sounds of explosions through the night as the first airborne troops engaged to the west of the airfield behind the beaches. In the first hour of dawn, his orderly retrieved him and drove him to the airfield area where he joined with the others around the fighter planes parked in the woods.

He told his interviewer that when nearing the satellite airfield, probably Évreux/VI near Le Bos Hion and Reuilly, “We saw a peculiar sight, so baffling that we stopped and stared. This was an Allied glider which had crashed into one of the meadows, and it was just sitting there on its belly, apparently abandoned. In retrospect, this must have been a single glider which had drifted inland from the attacks on the coast, but the sight of it alarmed us.” The glider troops, however, were long gone, having moved out to find and engage the German Army elsewhere. Most likely, they never knew that they had landed nearly adjacent to a German airfield, where they could have done extensive damage.

The First Confusing Morning Hours

Soon after arriving, the Luftwaffe pilots were briefed about the airborne invasion at Carentan, well west of the airfield. They ate a quick breakfast and then, from their hidden revetments, they watched in the distance as an American Fighter Group of P-38 Lightnings rigorously attacked the decoy airfield that they had set up nearby, which included fake runways, fake buildings and hangars, and other airfield facilities meant to deceive attacks from the air. This was called Évreux-Huest and was located approximately at 49º 02′ 29″ N – 01º 12′ 43″ E, just north of the small village at Huest.

At approximately 6:30 am, the pilots got into their cockpits and waited for orders. Several times, information was delivered by runners but no orders to launch came. After three hours, at approximately 9:00 am, orders were delivered to take off and attack any air targets that they could with priority given to attacking troop transport planes and bombers. Before engines could be started, the orders were rescinded. Overhead, the pilots could see hundreds of Allied aircraft passing in waves, crisscrossing the sky north and south.

Later in mid-morning, probably sometime around 10:30 am or 11:00 am based on the context of the pilot’s interview, the squadron commander ordered three fighters to take off on an armed reconnaissance patrol. Their mission was to get an aerial view of the unfolding situation along the beaches of Normandy to the west-northwest. At that point, given the damage done to German communications lines, the base and many other German units were in confusion as to what was happening. The commander gave Leutnant Beike his personal Leica aviation camera, asking him to photograph what he saw. Engines were started and the three planes quickly taxied out to take off.

Take Off and First Engagement

The three Messerschmitts moved quickly to take off individually in rapid succession. Each of the pilots immediately retracted their landing gear and pushed their throttles hard forward to gain as much airspeed as possible. Leutnant Beike was the second plane off the ground. Once aloft, the three planes quickly joined up into what he called “a staggered formation of three, separated by altitude”. They took a westerly heading toward Caen.

As the three Luftwaffe fighters leveled off at low altitude, a pair of P-51D Mustangs swooped down from the 4 o’clock position (described as coming from the direction of “120 degree point”, which would essentially mean coming from the northeast as the planes flew westward). Achieving complete surprise, the Mustangs opened fire as they flashed through the German formation. Finishing their first high speed firing pass, they pitched up into a climbing turn to come back around for a second attack. One of the three Messerschmitts was hit. It was the one flown by the pilot who had just celebrated his 25th birthday the night before. Leutnant Beike watched as it caught fire.

Leutnant Beike stated, “He began to make a lot of grey smoke as he turned away. As he banked below me, I remember that an orange glow began to spread from his engine. I remember that I groaned, knowing what this meant, and in a few moments his cowling few off in pieces and flames shot back over his cockpit. I could not look properly, because the air was full of these damned Mustangs, but I remember seeing him with his arms over his face, like this… and then he was simply lost in all the flames.” The pilot made a brave effort to return for a landing but was killed when his Messerschmitt exploded on final approach.

There was no time to tarry and, knowing that the P-51D Mustangs would soon be back for another attack, Leutnant Beike pushed the nose down and headed west-northwest straight for the coast. His throttle was rammed all the way forward. In the dive, his Bf 109G accelerated to over 600 km/hr, which was over its maximum speed. He was able to escape as two P-51Ds pursued him. At this point, he lost sight of the third Messerschmitt. He never saw it again. Apparently, it too was lost that day. He confirmed this when he noted at the end of his interview that he was the only survivor of the three who took off.

At the Beaches of Normandy

About 7 to 10 minutes into a flight (of about 110 km, roughly 70 miles), he reached the coast, probably near Ouistreham. “The coast itself just leapt up at me at that speed,” Leutnant Beike said, “and from that height I could then see a massive line of ships out at sea, about three kilometres from the shore. This just happened like that, in the blink of an eye… my canopy glass was just full of these ships. I was astonished at this sight. I wondered if I was hallucinating, or if this was a delirium of some kind. I had never seen such an assembly of ships, and I’m sure nobody will ever see such a thing again, perhaps not in human history. The sea was absolutely solid with metal, that is no exaggeration.”

He turned quickly to proceed west over the coast, on the land side over the German Army defenses that made up the so-called “Atlantic Wall”. To look down and to the right at the beaches and fleet offshore, he banked the wings of his Messerschmitt as he flew. Based on the description, he would have passed over the beaches that the Allies had code-named Sword (British Sector), Juno (Canadian Sector) and Gold (British Sector). At the time of the interviewer, Dieter Eckhertz, thought these were just Gold and Juno beaches, though a careful assessment of the maps points to his flight having been almost certainly over all three beach sectors that morning.

Leutnant Beike reported, “I saw that the beaches were crammed with vehicles, moving in on transport barges, and even tanks were being unloaded like that…. Throughout the beaches, there were fires burning, vehicles and boats on fire, and explosions from artillery. I saw flamethrowers being used inland, very powerful ones, and the flames lit up a wide area down there. The enemy were driving a bridgehead inland, that was clear to see, and they had enormous resources building up on the sand waiting to move off. I could see flashes of bombs and shells all over the inland area. I remember that some of the fields were flooded, and the exploding shells sent out concentric shock waves through the water that was very noticeable.”

All around him, the sky was full of Allied aircraft. He described it as a “low umbrella of fighters over the beach, and they came straight for me.” With so many American planes on the hunt, Leutnant Beike was in trouble. He was vastly outnumbered. Within a couple of minutes, he saw the first three USAAF Mustang fighters rapidly closing in. Realizing that there was no way to proceed westward along the beach anymore — he had flown over perhaps 30 km of beach and was probably near Arromanches — he turned to the southwest and headed inland, hoping to evade. At the speeds he was flying, his flight over Sword, Juno, and Gold Beaches was completed in just over three minutes. With the P-51Ds closing in, there was no chance to continue westward over the American beaches of Omaha and Utah. Those were just to the west.

“There were three [Mustangs] coming after me. I went down to minimum height and maximum speed, which was safe because the land is so flat there, and the German Flak would be less likely to misidentify me, I hoped. I thought that if I could move away from the beach head, the Mustangs would turn back to protect their sector. So I used a huge amount of fuel accelerating to the South West.” Maximum speed at sea level in a Messerschmitt Bf 109G with full boost and blower pressure is approximately 515 km/hr (which is 320 mph based on RAF flight tests). This meant that he was flying over 9 km per minute, about one kilometer ever 6.5 seconds.

At full power, the Messerschmitt was a hard target to catch in an extended tail chase. Leutnant Thomas Beike continued, “I went west as far as Saint Lô, and I couldn’t see the Americans behind me, so I turned East and followed the forest back towards Évreux.” Having evaded his attackers, Leutnant Beike continued to the base, intending on landing and relaying a report of what he had seen. As he raced at low altitude over the Normandy countryside east of Saint Lô and toward Caen, he could see masses of German Wehrmacht troops and vehicles along the roads and spread out into the fields and wood lines.

After Caen, he passed Lisieux and Bernay enroute to Évreux. Arriving to the satellite airfield at Évreux, he could see the burning wreckage of his colleague’s Messerschmitt at one end of the runway. The satellite field was already under attack. Amidst a strafing attack by USAAF fighter planes, he landed and rolled to a stop. Without delay, he jumped from the cockpit and ran for cover in one of the slit trenches alongside the field. He described the situation as follows: “The smoke from this burning plane was a beacon to the American planes, who came back just like a pack of wolves. I landed as they were strafing again, and I had to jump straight into a slit trench on top of the ground crew.”

In between bombing runs, he jumped up from the slit trench and ran to the main shelter hidden in the trees. Once there, he submitted his reconnaissance report, only then realizing that despite having had the commander’s Leica camera at his side in the cockpit, he had completely forgotten to take even a single photo. Given the situation, his oversight is certainly understandable, but we can only wish today that he had snapped even just one photo — it would have been historic.

With the continuous attacks, his satellite field at Évreux was taken out of action for several hours. Without orders and in the confusion of events — as well as considering the overwhelming air superiority that the Allies enjoyed overhead — Leutnant Thomas Beike did not get into the air again for the rest of the day. Only after moving to another of the satellite airfield southeast of Évreux, was he able to fly in the days that followed. He was subsequently injured in combat and sent to a hospital in Normandy to recover. This was subsequently overrun by US Army forces and he was captured without a shot being fired. As a result, against all odds, he survived the war. He spent the next year as a POW.

Final Notes

Leutnant Thomas Beike’s flight over the beaches was extraordinary. To make it, he had to use every bit of speed and skill he had, flying low and at the highest speed. Three German fighters took off, but only one returned. Throughout his flight, he was repeatedly chased by USAAF fighters. Always outnumbered, it is nothing short of a miracle that he survived at all. Even his landing was fraught with danger as he landed in the midst of an attack on his airfield. He never fired a shot, but returned with the mission completed as ordered. His report was sent up the chain of command, clarifying the situation on the beaches that morning.

Of course, by the time he flew, perhaps at around 10:30 am or 11:00 am, though no precise time is stated, the beaches he flew over were already in Allied hands. The German Army was hopelessly outnumbered and, while they could slow the Allied advance, once the beach heads were secure, the vast numbers of troops and vast amounts of materiel and supplies that landed overwhelmed any hope the Germans had of defending France. By late August, the Luftwaffe airfield at Évreux was in Allied hands and Paris was liberated. The Allied advance was unstoppable.

OTHER DATA AND RESEARCH

Allied Dominance in the Air

By June 6, 1944, 73 years ago in aviation history, the Allies had established nearly complete air superiority over northern France, including over the beaches at Normandy. During the early morning hours of D-Day, wave after wave of C-47s towed gliders and delivered paratroopers behind the beaches. Their mission was to interdict logistics, cut communications lines, sow confusion, and take out key defenses, including many of inland coastal fortresses. These were the heart of the Atlantic Wall and housed naval guns that were sighted on the beaches. Few Luftwaffe night fighters could challenge the vast aerial armada. Only the Luftwaffe’s Flak gunners were active.

At dawn, heavy bombers, such as B-17 Flying Fortresses and B-24 Liberators, dropped tons of bombs on German defenses behind the beaches. A low haze and cloud cover obscured the beaches in the early morning hours, however. As a result, most of these were inaccurate. Even the low flying B-17s were not challenged except by Flak. The USAAF’s and RAF’s medium bombers hit key road junctions, rail stations, depots, radar sites, and airfields. With the dawn, “Jabos”, the German name for Allied ground attack fighters like the P-47 Thunderbolt moved in. They flew low altitude ground attack missions against targets of opportunity. Meanwhile, multiple Fighter Groups of P-51s, Spitfires, Hurricanes, and other planes patrolled the skies for any sign of the Luftwaffe’s fighters and bombers.

At the small airfield near Évreux, P-38 Lightnings made an attack to ensure that the Luftwaffe’s assets that were based there were kept on the ground. The base supported both German fighters and bombers. As Leutnant Beike related, the P-38s hit the Luftwaffe’s newly constructed satellite airfields surrounding the old French-built base. First, they shot up a decoy field that the Germans had constructed. After the attack, Évreux, one of the new hidden bases that had been constructed to the east of the D-Day beaches, was still operational. Most of the rest of the Luftwaffe’s Normandy airfields, however, were taken out of action for the whole day.

Richard “Dick” Hallion, a well-regarded aviation historian, states that the RAF’s tactical air forces had 2,434 fighter and fighter-bomber aircraft to use on D-Day. As well, they fielded approximately 700 light and medium bombers. The USAAF was heavily engaged in an all-out effort and had more planes in the attack. The numbers of those are not readily available. Likewise, another historian (C.P. Stacey) reports that RAF Bomber Command flew 1,136 sorties with its heavy bombers against the German-held areas behind the beaches the night both before and during that day. Against this massive force, the Luftwaffe had insufficient strength in France to adequately defend. What few were there were mainly grounded due to damage to their airfields or simply as a result of the confusion that comes with the “fog of war”.

“The Luftwaffe Did Nothing”

There is an oft repeated claim that “the Luftwaffe did nothing” on D-Day. Most believe only that there was just one Luftwaffe flight that flew over the beaches that day, a pair of Focke-Wulf Fw 190A-8s lead by the German ace Josef Priller with his wingman, Sgt. Wodarczyk. This is wrong, however.

Months of continuous pounding by the Allies on their airfields, logistics, and fuel supplies had curtailed much of the Luftwaffe’s pre-1944 power. By D-Day, many aircraft were unable to fly. The air superiority that the Allies had established over Northern France by early Summer 1944 had taken its toll, downing many of the veteran pilots before the invasion. Younger pilots with far less training filled the ranks. Drug use, including heroin, cocaine, and especially amphetamines, was common. Alcoholism was increasingly a problem for the survivors, who were literally being flown to death against overwhelming odds. What Luftwaffe forces remained were hidden along the edges of forests and by roads, from which they could only hope to launch quick strikes and then return before being intercepted and shot down.

Thus, it wasn’t so much that “the Luftwaffe did nothing” — it was that they were worn down, grounded for lack of spare parts, and attacked relentlessly to ensure that they could not threaten the invasion. The pilots, exhausted and demoralized from months of tension and continuous engagement, did what they could. The few who took off showed extraordinary bravery.

Other Known Aerial Engagements

The first engagement of the day was apparently a single night fighter that flew well west of their usual patrol area around Holland and Belgium and chased what was probably an RAF Avro Lancaster on its way back to its base after dropping bombs on a target deeper inland. Tracer fire being exchanged between the night fighter (of unidentified type) and the Lancaster was visible in the night skies.

Later, before dawn broke, a flight of four Fw 190s from 3/SKG 10 (3rd Squadron of Schnellkampfgeschwader 10), lead by Hauptmann Helmut Eberspächer, took off. These were daylight fighters that Hauptmann Eberspächer lead into the air in the pre-dawn hours. Over the course of a two hour flight, in the pre-dawn light and precisely at 5:01 am, the four Fw 190s intercepted four RAF Avro Lancasters heavy bombers as they were making their way back toward England. Within the next three minutes, all four Lancasters were downed, the first falling at Isigny-sur-Mer and the others near Carentan. None of the German planes were lost in the attack. One of those was the RAF Avro Lancaster ND739 flying with No. 97 Squadron RAF (Pathfinders) from RAF Coningsby. The plane was piloted by the squadron’s commanding officer, Wing Commander Jimmie Carter.

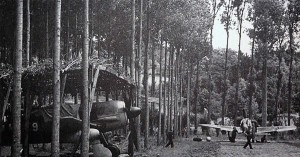

Just a half hour later, as the invasion began, a Luftwaffe bomber wing, Kampfgeschwader 54 (KG 54), launched the first of a series of attacks with Junkers Ju 88s on the easternmost beachhead where the British Army was landing at Sword Beach. Repeated bombing raids were made throughout the morning, despite overwhelming Allied air superiority and the threat of interception. First, the planes were loaded and fueled in hidden, tree-lined revetments. Then they took off for a quick dash to the beaches to drop their bombs and race back for a landing. Once back on the ground, they were again hidden in the trees, rearmed and refueled before taking off again on another desperate raid.

These missions employed so-called Butterfly Bombs, which in Luftwaffe parlance were called Sprengbombe Dickwandig 2 kg (SD2). These bombs were the first “cluster bombs” and, once dropped, they dispersed up to 108 submunitions widely as an anti-personnel weapon. The other attacks mounted by KG 54 on Sword Beach were as follows: a) III./KG 54 attacked Lion-sur-Mer by air; b) I./KG 54 attacked Allied shipping while it was anchored off the mouth of the River Orne. This latter attack, however, was costly as five of the Luftwaffe bombers were shot down by No. 145 Wing RAF.

As well, there were attacks against the British forces at Gold at sunset on June 6, well after the beach head was established. Several flights of Luftwaffe bombers caused damage and casualties at Le Hamel. Others bombed and damaged a road near Ver-sur-Mer, hoping to slow the British advance inland.

Also that evening, II/KG 40 made a daring, massed attack, flying 26 Heinkel He 177 heavy bombers in a large formation to attack Allied shipping off Gold Beach. These heavy bombers were equipped with one of the Nazi “super weapons”, the Henschel Hs 293 anti-ship guided missiles. However, Allied air and AAA was effective and the II/KG 40 lost 13 of its heavy bombers in that attack, fully half the force. It is unclear how much damage was done in these attacks but at least some of the missiles likely hit Allied ships.

Finally, records of Luftwaffe bases in the vicinity were collected and summarized by history Henry L. deZeng IV. Those indicate that the main field at Évreux was east of the city and called Évreux/Ost (Position 49º 01′ 30″ N – 01º 13′ 20″ E). It was largely used as a Luftwaffe bomber base from 1940 until 1944. The airfields HQ was located in two châteaux, both at Le Breuil nearby. At the time of D-Day, the field had a number of active satellite fields with the planes concealed in the treeline and forests around the fields.

These were:

- Évreux/I, located just west of the French village Miserey at approximately 49º 01′ 14″ N – 01º 15′ 18″ E with grass runways measuring 1350 yards long and 200 yards wide.

- Évreux/II, located just south east of the French village Huest at approximately 49º 01′ 57″ N – 01º 12′ 59″ E with grass runways measuring 1650 yards long and 200 yards wide.

- Évreux/VI, located 5.5 km north-northeast of the original French-built airfield at Évreux, south of the French villages Le Bos Hion and Reuilly, at approximately 49º 01′ 57″ N – 01º 12′ 59″ E with grass runways measuring 1400 yards long and 250 yards wide.

- Three other satellite airfields, III, IV, and V, were still under construction at the time of D-Day.

Excellent information. The comment about the Luftwaffe flying without synchronizing their engines caught my attention. I fly an O-2 and recently I had the opportunity to fly with a Vietnam vet who had flown my airplane (the very same plane) over SEA. He said that they were instructed to fly without synchronizing the props as it was believed that this made it difficult to track or precisely locate the airplane by ground observers. I wonder if the Luftwaffe had the same idea?

Thanks for a well researched and well written account.

Having seen “The Battle of Britain”, I was also under the impression the German Luftwaffe’s effort to stop the invasion was limited to one or two sorties. But this excellent article shows, although futile, there were some others. The overwhelming numbers in which the Allies turned up is what rendered the Luftwaffe unable to effectively counter. Thanks for the article.

What is the translation of ‘Jagdabschnittfuhrer. The Jagd is fighter and the fuhrer is leader, but not sure about the schnitt bit.

Ian White

Martlesham Heath

Suffolk

England

Great article, thank you so much, and a good tip for a book. One sentence caught my attention — “Drug use, including heroin, cocaine, and especially amphetamines, was common.” Can you please give a citation for this? My research and primary interviews with Luftwaffe pilots and German veterans in general shows that drug use was relatively uncommon, even the use of Pervitin. Many thanks.