Published March 23, 2018

By Ron Miller/io9

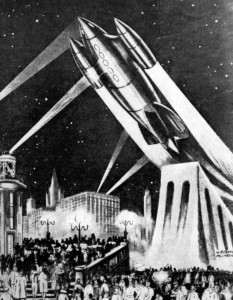

A stubby-winged plane launches itself from an airport runway on the outskirts of Berlin. When it reaches an altitude of several miles, it fires its rocket engines, lifting itself high into the stratosphere. Then, its rockets shut down, it soars smoothly across the Atlantic Ocean. On board, its passengers are strapped into cushioned, contoured seats, enjoying their first experience with weightlessness. If they don’t like the experience, they can comfort themselves with the fact that free-fall will only last 20 minutes, after which the rocket will begin its descent back into the atmosphere. Barely half an hour after leaving Germany, the rocket touches down near New York City.

This was the dream of Max Valier,a German born in Boen, in the southern Tyrol (now part of Italy) in 1895. While it may sound like a modern science fiction story or some futuristic fantasy vision of space travel, this was exactly scenario proposed by the first space entrepreneur more than 80 years ago in the 1930s. If any of the current schemes for commercial spaceflight succeeds, they’ll owe a huge debt to a designer that most cannot even name. Sadly, not only was he a vision, but he was also the first martyr on the long road to develop of space travel.

Valier was a precocious child long interested in astronomy. He was the author of dozens of books and pamphlets on the subject and invented the rotating star chart, also known as the “planosphere”. The planosphere is still in use, testimony to its fine design and educational merit.

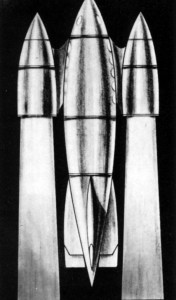

Valier first learned about spaceflight after the publication of Hermann Oberth’s “Die Rakete zu den Planetenraum” in 1925. Thereafter, he wrote a popularized version of Oberth’s book and this became an international best-seller. Through his efforts, he popularized the idea of spaceflight popular throughout Europe. Valier’s vision of rocket travel, however, was not simply a pipe-dream. Rather, it was devised from the start as an evolutionary development effort to build on existing technologies until ultimately the products was a crewed spacecraft capable of transatlantic travel.

To get his project off the ground, finding investors and supporters, Valier was acutely aware of the need for public education. Therefore, he lectured regularly and poured out dozens of articles for publication in the media. These were translated and reprinted in many newspapers and magazines around the world, often without credit. As a result, he and his plans became almost as well-known and influential as von Braun and his “Collier’s” space program were to become in the 1950s.

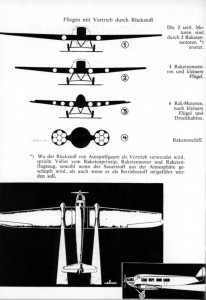

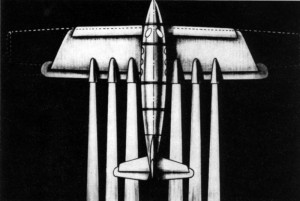

Valier’s greatest contribution was that he developed an incremental, evolutionary approach to the development of the spaceship. He began with an ordinary commercial aircraft. Step-by-step through different generations of design, this would gradually develop into rocket-assisted flight and then into full-fledged rocket transport. Finally, it would result in a wingless interplanetary spacecraft. He also promoted the idea of a transatlantic passenger rocket. He envisioned that this would make the trip from Berlin to New York in less than an hour.

At the same time, Valier collaborated with industrialist Fritz von Opel (of the famous automotive company) and signal rocket manufacturer F. W. Sander to demonstrate the practicality of rocket-propelled vehicles. This led to a whole series of spectacular experiments that saw rocket-powered cars, sleds, rail vehicles, take to test tracks. This added to the public relations interest that he was creating for his rocket ship. Those development efforts culminated in the flight of the first rocket-propelled aircraft in 1929.

Even though his contributions were discounted by space flight historians such as Willy Ley, who thought Valier’s demonstrations were nothing more than useless publicity stunts, his experiments were enormously valuable in “selling” the idea of rocket propulsion to the general public. There’s no denying that the possibility of rocket flight and space travel was on everyone’s lips at the time — and that this was the result of Valier’s work and unceasing promotional efforts.

Unfortunately, the car designer Fritz Opel, who was just in it for the publicity, took most of the limelight from Valier. Opel even denied Valier, who was an experienced pilot, the honor of making the first rocket plane flight, despite the fact that Valier designed the plane. Valier, undeterred, went on to work on developing liquid-fueled motors, as well as plans for long-range, liquid-fueled rocket planes.

The effort, however, lead to his untimely death. While working on developing a liquid-fueled motor, Valier was killed in an explosion.

Max Valier is largely forgotten today, but he stands head and shoulders above nearly all others as one of the great pioneers of spaceflight. Even if he didn’t contribute much to the technical development of astronautics, he was instrumental in establishing public acceptance and support for rocketry and promulgating the idea of practical spaceflight for the masses, which remains a dream even to this day.

In the end, Valier’s educational and public relations work inspired an entire generation of future engineers and scientists. The dream of spaceflight that many today still hold dear is the direct product of his dream and vision.

From the Archives

In the late 1920s, Fritz von Opel, the grandson of Adam Opel and the founder of the famous German car manufacturer Opel, had a dream. While others in his family were focused on automobiles, Fritz had a penchant for rockets. As experiments, he had mounted rockets on the back of two racing car designs. This proved to be excellent publicity stunts and helped expand the family car company’s reputation and business. Yet Fritz von Opel was unsatisfied — he would design a rocket plane.

=> Read about Opel’s Rocket Plane!