Published on April 28, 2013

The Flight Data Recorder, most would say, traces its lineage to the first efforts of two Frenchmen, François Hussenot and Paul Beaudouin, who created their revolutionary “HB” device in 1939. The HB used photographic processes, in which an eight meter long, 88 mm wide film recorded the progression of altitude, speed and other flight data onto film. The film was changed periodically since, once exposed, it could not record additional data. Another early design was created by Len Harrison and Vic Husband in the early 1940s, whose apparatus record flight data and control positioning onto copper tape, which could therefore survive a crash.

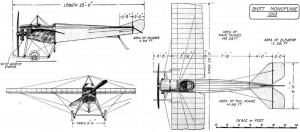

Both reports on the origins of the Flight Data Recorder are wrong, however. The first true flight data recorder dates not to the late 1930s or early 1940s, but rather decades earlier to a man whose contributions to aviation are all but forgotten — the Englishmen Mr. George M. Dyott. His aeroplane, known as the Dyott Monoplane, debuted in April 1913, 100 years years ago in aviation history. Surprisingly, it carried the world’s first Flight Data Recorder, a device of his invention.

The First Flight Data Recorder

As historical records clearly show — even if they’ve been largely missed by others — Dyott’s first device wasn’t experimental, but rather was offered as standard equipment on Mr. George M. Dyott’s monoplane in 1913. The existence of the device is beyond question — it was not just an idea “on paper”, but rather was installed and operational on all of Dyott’s monoplanes.

Even the publication Flight, the newsletter of the Royal Aero Club, contained an announcement about the device, which they credited to Mr. Dyott as his own invention. Their entry from the April 26, 1913, newsletter provides a complete description of the device’s operating principles:

In addition to the usual instruments carried, i.e., revolution indicator and altimeter, this machine is fitted with an instrument of Mr. Dyott’s own invention. It is a graphic recorder which shows all the different movements of the control levers. The chart is divided into three parts: Warp, Elevator and Rudder. As the drum revolves, three pointers draw the three different graphs, so that in a straight flight, during which the control levers were not moved at all, the pointers would draw three straight lines, but as soon as the course was altered the pointer connected to the rudder would make a wavy line, and as the warp is used in conjunction with the rudder, the warp pointer would draw a corresponding curve. This instrument should prove of great service, and furnish some very interesting data for comparing the different ways in which different pilots control the same machine.

Thus, as incredible as it might seem, by tracking the movements of the three axis control inputs, the original Dyott invention has much in common with later flight recorders, just as those developed in the 1940s!

Dyott’s Monoplane

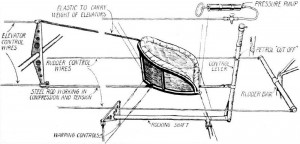

As for Dyott’s Monoplane, it included other innovations as well his Flight Data Recorder, though he didn’t call his invention that, though exactly what he named it is unclear. The overall design and plan form conformed the latest standards and expectations, similar in appearance to a Morane, Blériot or Deperdussin. The engine was a 50 hp, seven cylinder Gnome radial, a popular power plant of the day. Based on the size of the fuel and oil tanks, the pilot could expect a three hour endurance — another innovation in Dyott’s design was the addition of a secondary fuel tank, located behind the pilot’s seat.

To address the widely discussed and troublesome issue of elevator wire chafing that plagued other aircraft designs of the time (e.g., the wires from the stick to the tail had to cross or control inputs would not be correctly applied), Dyott developed a unique system involving a single wire from the control stick to a rocker arm that likewise attached to the aviator’s own seat. This allowed leverage to manipulate the elevator without the need to cross the wires.

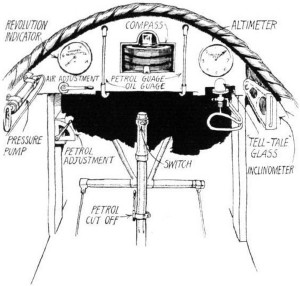

The layout of the cockpit and instrument panel, though simple by modern standards, was carefully considered and organized in a way that would impress later instrument panel designers. Engine controls and instrumentation were co-located on the left side, with levers to allow the pilot to control the fuel and air flow into the carburetor while referencing an RPM indicator, as a vertical glass tube gave visual reference to the oil level in the tank. The magnetic compass was at the center of the panel. To the right were the altimeter, the fuel glass and the “tell-tale glass” as well as an “inclinometer”. A joystick with rudder pedals, as seen in modern control systems, were positioned in front of the seat while a fuel cut-off switch was located on the left side of the joystick to enable chopping the engine for descents and landings, easily found without the pilot having to glance down at the panel during the concentrated periods of the final approach to landing.

Final Thoughts

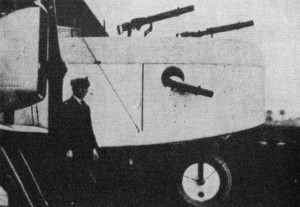

Despite all of its innovative characteristics, George Dyott’s monoplane didn’t exactly take England by storm. Though his design was appreciated for its merits, it flew a bit slowly, featuring a top speed of about 75 mph. Ultimately, he had to take it to America to find buyers. Even then, his monoplane design didn’t become as popular as the other competing aircraft types of the day. When the Great War began in 1914, Dyott’s monoplane saw little service — instead he concentrated on developing a large, twin-engine bomber for use by the Royal Navy, which he introduced in 1916. With three crew, four bomb bays and a biplane configuration, that design was also quite innovative.

Most critically, he pioneered the concept of the “flying fortress”, putting no fewer than five Lewis machine guns on the plane, pointing in all directions for defense. Two guns were mounted for the nose gunner, two fired through side ports on the fuselage (one on each side) and one was fitted to a rear-gunner station behind the wing.

Sadly, this design was doomed also from the start since the British Government only allowed Dyott to fit the plane with lesser powered, heavier, less reliable engines, retaining the best engines for the more common and popular aircraft that it sought to procure for the war effort. Instead, for the Dyott Bomber a pair of 120hp Beardmore six-cylinder, water-cooled, in-line engines were used, leaving it dramatically under-powered. Later, these were upgraded to 230 hp versions, but even then the plane never left the testing fields, finally being scrapped in 1918/1919 at the end of the war.

Ultimately, George Dyott proved to be a very capable and innovative designer — even visionary in many respects. Many of his ideas were years ahead of the standard of his day, though few recognized it at the time. One can only imagine how much the world could have benefited from his Flight Data Recorder during those early years, as it would have given accident investigators far more insight into what really happened in the wake of each crash. When the Flight Data Recorder was developed in the first years of World War II, it is quite likely that little or no reference was made to Mr. Dyott’s device — thus, the FDR would suffer the fate of having been invented twice!

From the Archives

100 Years Ago :: Flying in Mexico — read about George M. Dyott’s extraordinary adventures flying in Mexico, complete with a photo of the man himself!

Today’s Aviation Research Question

As we cannot find one, does anyone have a photograph or diagram of Mr. Dyott’s data recording device?