Published on September 12, 2016

By Thomas Van Hare

“A Parisian automobile paper recently published a letter from the Wright brothers to Capt. Ferber of the French army, in which statements are made that certainly need some public substantiation from the Wright brothers.”

So began an article in the January 13, 1905, issue of the Scientific American, entitled, “The Wright Aeroplane and its Fabled Performance”. Skeptical of the claims made by the Wrights, that not only had they successfully flown their aeroplane, but that they had also set numerous records, the magazine’s editors spared no enthusiasm in challenging their honesty.

The magazine’s problem, of course, was that it was entirely true, though it didn’t know it at the time. In fact, for years after the Wright Brothers first flew at Kitty Hawk, the United States was blissfully unaware of their great achievement.

The Wrights had tried to find buyers and officials who would be interested in seeing their machine, but they were instead given the cold shoulder. New reporters in the USA ignored their claims, thinking them preposterous. Their inquiries to set up meetings with government officials in Washington were ignored. The US Army never replied to their letter, despite what should have been the obvious advantage of a working aeroplane to the military campaign.

Finally, exasperated that nobody believed their claims, the Wrights had opened up contacts with potential European buyers by mail and telegraph. Their response was far more welcoming. They believed the Wrights’ claims and wanted them to come across the Atlantic for demonstrations.

Even with the open invitation, it would take the Wrights more than another two years to box up their aeroplane and get it to France on a ship. Such ocean voyages at that time were major ventures, whereas today — in large part because of the early pioneering work of the Wrights themselves — today you can just purchase a ticket and fly across the Atlantic in eight hours.

Once the Wrights did arrive in France, it wasn’t long before they were thrilling crowds with their demonstration. Further, they opened more serious negotiations to license their invention to the French military (earlier reported in the Scientific American itself as being for a fee of 1 million Francs). For the Wrights, Europe was the promising business venture they had needed — any funding was welcome since the bicycle shop had sustained them for so long and could only do so on a shoestring budget.

The Scientific American’s editors, however, could not have foreseen how the Wrights would be welcomed just three years after they published their doubting article. In that 1905 article, they had cited the many records that the Wrights had claimed to have set. The editors’ tone was dripping with sarcasm and disbelief. Perhaps the only reason they reported accurately on the distances and times flown of each record was to support their belief that it was all a pack of lies. That these record-setting flights had taken place in America and had been documented mattered little to them — they still were in doubt.

In the letter in question it is alleged that on September 26, the Wright motor-driven aeroplane covered a distance of 17.961 kilometers in 18 minutes and 9 seconds and that its further progress was stopped by lack of gasoline. On September 29 a distance of 19.57 kilometers was covered in 19 minutes and 55 seconds, the gasoline supply again having been exhausted. On September 30 the machine traveled 16 kilometers in 17 minutes and 15 seconds; this time a hot bearing prevented further remarkable progress. Then came some eye-opening records. Here they are:

- October 3: 24.535 kilometers in 25 minutes and 5 seconds. (Cause of Stoppage, hot bearing.)

- October 4: 33.456 kilometers in 33 minutes and 17 seconds. (Cause of stoppage, hot bearing.)

- October 5: 38.956 kilometers in 33 minutes and 3 seconds. (Cause of stoppage, exhaustion of gasoline supply.)

The Scientific American, despite its authoritative position and scientific approach, was having none of it. The editors made reference to the best-funded effort at achieving powered flight in the United States, that by Professor Samuel Langley, who had crashed his government-funded airplane into the Potomac River.

“It seems that these alleged experiments were made at Dayton, Ohio, a fairly large town, and that the newspapers of the United States, alert as they are, allowed these sensational performances to escape their notice. When it is considered that Langley never even successfully launched his man-carrying machine, that Langley’s experimental model never flew more than a mile, and that Wright’s mysterious aeroplane covered a reputed distance of 38 kilometers at the rate of one kilometer a minute, we have the right to exact further information before we place reliance on these French reports.”

A Penchant for Secrecy

The Wrights’ own penchant for secrecy worked against them. They were simply hoping to protect their knowledge so that they could capitalize on it and make money, however, that reticence at public display worked against them. Many were left in the opinion that they were fabricating their claims. As the Scientific American argued:

“Unfortunately, the Wright brothers are hardly disposed to publish any substantiation or to make public experiments, for reasons best known to themselves. If such sensational and tremendously important experiments are being conducted in a not very remote part of the country, on a subject in which almost everybody feels the most profound interest, is it possible to believe that the enterprising American reporter, who, it is well known, comes down the chimney when the door is locked in his face — even if he has to scale a fifteen-story sky-scraper to do so — would not have ascertained all about them and published them broadcast long ago?”

That the Wrights were selling or licensing the rights to their invention to the French was met with disbelief. Indeed, the Scientific American noted, wouldn’t the US Government be a better buyer? What they didn’t know, of course, was that their letters to the government and military had been completely ignored.

“Why particularly, as it is further alleged, should the Wrights desire to sell their invention to the French government for a “million” francs. Surely their own is the first to which they would be likely to apply.”

The Celebrated Aviators in Europe

In 1908, when the Wrights finally made it to Europe, they were welcomed with open arms. After the first demonstration flight, the Wrights became the toast of France — and then the toast of the entire continent. The French aviators, who had been in an extraordinary competition with each other, as they struggled to perfect their own designs, were shocked at far ahead the Wrights’ design was.

The French aviators were afraid of tilting their aeroplanes in a turn, thinking that this would result in a crash. Instead, they would skid around, keeping the wings level, and try to orient the aeroplane with the rudder alone. However, the Wright machine, on its first demonstration flight shattered their illusions — Orville banked into a steep turn and then soared nimbly around the field, taking the Flyer wherever he wished with seeming ease and confidence.

Léon Delagrange, one of France’s leading aviators and designers, was resigned to the simple fact that the Americans had beaten to mastering the air, despite the collective efforts of all of the French pilots in the Aero-Club de France. He quipped simply, “Nous sommes battus”, which translates from French as “We are beaten.” The comment was personal — just two weeks earlier, Delagrange had set the new record in France for the longest flight on September 6, 1908 — at 29 minutes, 53 seconds aloft. The Wrights didn’t just nudge past his record, but crushed it with a time of 1 hour, 31 minutes, 25 seconds — a flight they achieved on September 21, 1908, at Auvours. It would be nearly another year, on August 25, 1909, before another French aviator, Louis Paulhan, finally beat the Wrights’ record.

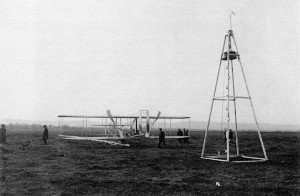

Orville and Wilbur’s sister, Katherine, was soon brought to Europe to organize the calendar of events and go to meetings as well as discuss their invention with potential buyers and meet celebrities, royalty, and nobility alike. The Wrights could not have managed it without her. It took a lot of time maintaining the aeroplane, setting up the launch track, and the weighted tower that launched the Wright Flyer into the air. She played a key role for them, ensuring that everything was properly handled — indeed, the Wrights’ efforts were a family business in all respects.

Katherine Wright proved perfect for the role. She was down-to-earth, direct, and entirely American in her unassuming nature. This won over the highest elites of Europe. She met with and was feted by the Spanish King, Alfonso XIII, the English king, Edward VII, and the King of Italy, Victor XX. The German Crown Prince, Friedrich Wilhelm, was enchanted by her and amazed at the Wrights’ aeroplane. The European journals, unlike the doubting American press, ate it up. To demonstrate confidence in their Flyer, Katherine was taken aloft as a passenger — twice — making her one of the very first women to fly.

In October 1908, from Le Mans, France, Wilbur Wright wrote that, “Princes & millionaires are thick as fleas.” Indeed, the three Wrights were celebrated as heroes and invited to dinners wherever they went. Crowds gathered for their demonstration flights and newspapers published breathless reports. The French military was astonished at the aeroplane that the Wrights had brought over and confirmed their interest in a business deal to license the technology.

Film of the Wright Brothers’ flights in France 1908

In the half year they flew in 1908, the Wright Brothers performed more than 200 demonstration flights in Europe. They traveled to Italy and demonstrated the aeroplane there as well. A licensing contract was negotiated to manufacture the plane in Germany. Finally, as 1908 came to a close, they were set to return to America. Ultimately, the Wrights would make three trips to Europe, marketing their aeroplane designs and licensing the construction of Wright Flyers.

During their first trip, the French government awarded the Wrights that nation’s highest medal, the Ordre national de la Légion d’honneur. This was awarded to both Wilbur and Orville Wright — and their sister Katherine, who had become nearly as famous as the two brothers for her own exploits and the key role she played. Indeed, she had been an essential part of their efforts from the beginning when they were struggling to develop the aeroplane. While in Europe, she took on a large role, even learning French so that she could serve as a partner in their business efforts.

Conclusion

The Scientific American article of 1905 could not have known that the Wrights European fans would soon be vindicated. Their piece ended with the insinuation of dishonesty when they wrote, “We certainly want more light on the subject.” Indeed, the Wrights would show their stuff in the end. They would secure their place in history for the first successful heavier-than-air powered flight.

In 1909, soon after their return to America, the US Army took an interest in the Wrights’ aeroplane. The first official trials were held.

At the Scientific American, few doubters remained.

From the Archives

When the Wrights demonstrated their Flyer to the US Army, they suffered a catastrophic crash, killing an early Army aviator and nearly killing Orville himself.