Published on November 29, 1944

The largest aircraft carrier built in all of World War II, Japan’s 72,000 ton Shinano, was well on the way to achieving operational status when the first B-29 Superfortress launched from Saipan and made a reconnaissance flight over the ship in dry dock at Yokosuka. Immediately, the Japanese Naval Command recognized that the Shinano would have to be moved or it would soon be targeted by the American heavy bombers. Yet the ship was not quite finished, its water tight doors were still being installed and had not been tested. Nonetheless, it was rushed to launch on November 19, 1944, and readied for sea. As the first B-29 attacks out of Saipan struck nearby Tokyo, the Japanese Naval Command ordered Shinano to make haste for Kure, in the southern Hiroshima prefecture on Japan’s inland sea. There, it was hoped that the final fitting out could be completed — at most, just a few months remained before Japan would launch a new aircraft with which to challenge American superiority in the Pacific.

Ominously, before departing Yokosuka, the ship was loaded with 50 of Japan’s new suicide rocket plane, the virtually unstoppable Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka, of which just 755 were built in all during last year of the war. The 50 aboard the Shinano constituted most of the Ohkas yet built at that time. They were loaded into the Shanano’s huge hangar bay, which could hold 120 aircraft. As the ship hoisted anchor, the Japanese Naval Command had no way of knowing that the American code breakers were intercepting their messages. As the US Navy’s top admirals and the US Army and Army Air Forces began to consider how to sink the Shinano, everyone realized that if it could be done, the impact on the war would be profound — but how to catch her?

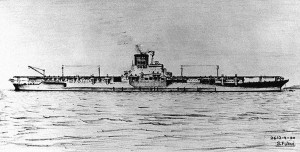

Japan’s Super Carrier

The Shinano was not only the largest aircraft carrier ever built, but also the best armored. Its flight deck was constructed of two layers of steel with the spaces in between packed with shock absorbing materials. Its sides were sheathed in steel plate and the fuel tanks that were intended to service her aircraft were surrounded by poured concrete. The ship was based on the same hull design that had been used in the construction of the Yamato and Musashi battleships. As a result, even the US Navy’s best dive bombers would have been useless against the ship — the heaviest bombs the Navy could drop could not hope to penetrate its deck armor. Only land-based air power had the capability of sinking the ship or perhaps an interception by US Naval assets.

As the Navy considered its options, interception by surface vessels seemed impossible — first the Shinano’s run down the coast was too short to allow a successful interception; and second, any American capital ships dispatched on the mission would be within close range of Japan’s land-based bombers and kamikaze aircraft. Likewise, intercepting the Shinano by submarine would be difficult since it was realized that the Shinano’s top speed exceed the best a surfaced submarine could achieve. In short, the ship would likely run away from any pursuing submarine. Bombing a ship at sea from high altitude aircraft was difficult and probably would have been ineffective, and not enough B-29 Superfortresses were yet operational on Saipan to give a high probability of success. Ultimately, there were few options.

As the ship left Yokosuka on November 28, 1944, the Japanese Navy executed a daring raid on Isley Field in Saipan, damaging some of the bombers there. This provided a window of opportunity to move the ship — or so the Japanese Naval Command hoped. Their greatest fear was the potential of an American submarine wolf pack which they felt might be able to coordinate an attack on the great aircraft carrier as it ran down the coastline toward Kure. Thus, they assigned a significant escort of destroyers to help guard the ship from submarine attack.

Attack on the Shinano

On November 29, 1944, today in aviation history, the Shinano, just ten days since its launch, met its fate. The largest aircraft carrier the world had ever seen was running down the coast, zigzagging to avoid possible submarine attack, when an American submarine was spotted behind the ship. As night fell, destroyer closed rapidly on the American attack submarine but the commander of the Shinano, Captain Toshio Abe, ordered the destroyer back. He feared that the submarine, which had been seen on the surface but was behind the ships, was a purposeful ruse to draw off some of his four escorts, leaving the Shinano unprotected and at the mercy of his imagined American submarine wolf pack.

As it happened, there was no American submarine wolf pack in place. The only submarine that had a chance of intercepting the Shinano was the one that had been spotted — and it hadn’t been stationed there to intercept Japanese shipping, but rather to serve as a lifeguard vessel to recover downed B-29 flight crews who might have parachuted or ditched into the waves south of Japan. This was the USS Archer-Fish (SS-311), a Balao-class submarine under Commander Joseph F. Enright, USN. The Shinano indeed was far too fast for the USS Archer-Fish, which was taking advantage of the gather night and running on the surface at full speed in the distant wake of the ship and its escorts. By chance, the submarine had made a first interception, but now it was far behind the Japanese vessels. In slim hopes of catching the Shinano, Cmdr. Enright ordered his crew to continue the pursuit on a direct course even as night cloaked the submarine’s pursuit.

Incredibly, Captain Toshio Abe ordered his ship to begin zig-zagging to throw off possible submarine attacks. Ill luck had taken two of the ship’s six boilers offline. With bearing problems on its shafts, the ship was running on just two of its screws and at reduced speeds. Thus, the aircraft carrier was reduced to about the speed of the pursuing USS Archer-Fish. If the Shinano had run straight down the coast toward Kure, the USS Archer-Fish would have never caught her, however, with every broad zig-zag, the Shinano allowed the submarine to close the gap. Six hours of the chase ensured until finally, as the Shinano executed another hard turn on its zig-zagging course, the Japanese aircraft carrier had placed the pursuing USS Archer-Fish on a near perfect interception course. This would allow the submarine to close within the escort screen and take a shot with its torpedoes. No longer trusting the night and pale moonlight for protection, the submarine’s commander ordered the USS Archer-Fish to periscope depth.

As he crept forward on a intersecting course, Cmdr. Enright watched through his periscope and saw one of the Japanese destroyers turn directly toward the USS Archer-Fish. Fearing that he had been spotted, he ordered the submarine to execute an emergency dive deeper as he lowered the periscope. Yet it was too late — the submarine was barely beneath the keel of the Japanese destroyer as it passed directly overhead. Aboard the Archer-Fish, the men waited for the sounds of depth charges splashing into the water above. Incredibly, none came. As luck would have it, the Japanese destroyer had not spotted the submarine after all. Now, having passed overhead, the Archer-Fish was inside the escort screen and steadily closing on the Shinano, which was running directly across her path.

As the Shinano loomed within range, his crew calculated the firing angles as Cmdr. Enright ordered the torpedoes’ running depth set for shallow. Knowing the heavy armor of the Shinano, he hoped to hole the great ship high up toward the waterline, which, if luck held, would lead the aircraft carrier to list to the side. A further firing solution could then be computed against the stricken and slowed carrier — he could only hope that this might result in it capsizing. It was 3:15 am when he ordered a rapid firing of six torpedoes — the Shinano was was just 1,400 yards distant, incredibly short range for a torpedo attack. The track of the six torpedoes was true and they ran straight against the side of the huge aircraft carrier at a near perfect angle.

The End of the Shinano

As it happened, four of Cmdr. Enright’s six torpedoes hit the Shinano squarely and exploded in quick succession. As the blasts rocked the aircraft carrier, Captain Toshio Abe shrugged off the hits, trusting in the great ship’s armor. Instead, he kept the ship running at top speed. It was a terrible error — below decks, the Shinano was not only holed but, with the speed of the ship’s progress, now at 18 kts, the forces of the rushing water hydraulic’ed millions of gallons of sea water into the ship. As the crew slammed shut the ship’s untested water tight doors, they were shocked to see the rivets popping. Many of the doors flooded back open. In other areas of the ship, the flooding was so rapid that the crew could not hope to arrest it. Hundreds of men were trapped on lower decks as the water flooded in above.

Within minutes, the greatest aircraft carrier the world had ever seen was listing 10 degrees to starboard. Captain Abe ordered counter flooding to reduce the list. This worked only partly. After four hours, the continued flooding overcame these small defensive measures and the boilers were taken off line as the ship began to settle. As the Shinano came to full stop on the waves, its list increased to 30 degrees. With the flight deck now touching the water, it was clear that the end was nearing. At 10:18 am, Capt. Abe ordered the crew to abandon ship. Even as the men ran topside and leapt into the water, the great vessel heeled over further. Horribly, the yawning hole of the ship’s main deck elevator began to take on water, sweeping hundreds of men back into the ship as if into a huge drain.

At 10:57 am, the Shinano capsized and sank beneath the waves. When she sank, 1,435 men and officers, along with Capt. Abe, were dragged into the depths of the sea. The great ship sank just 120 miles off the coast of Japan. Another 1,080 men survived and were picked up by ship’s escorts as the USS Archer-Fish crept away unscathed. The threat of Japan’s super carrier was thus ended — no doubt, it had been a stroke of luck but also the result of an effort that had spanned the entire War Department, from the decoders to the USAAF and the entire US Navy. In the end, however, it came down to one submarine and a singularly brilliant Naval officer, Cmdr. Joseph F. Enright, with his dedicated crew.

One More Bit of Aviation History

The Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka rocket kamikaze planes were a deadly weapon, perhaps one the most deadly aircraft types in the Japanese arsenal. As with all kamikaze missions, the pilots were expected to fly their planes directly into American ships, sacrificing their lives and inflicting terrible damage in the process. Whereas other Japanese kamikaze aircraft were all slower, propeller-driven types, the Ohka (nicknamed “Baka” by the Americans, which translates to “Idiot”) were powered by three solid-fuel rockets. The Ohka’s were to dropped from another aircraft (typically a Mitsubishi G4M2e “Betty” Model 24J bomber from outside of the range of AAA fire. Then the pilots were to point the nose of the Ohka downward in a fast glide, using the rockets one by one as necessary to extend their range. Ideally, they would ignite all three at once in the final stages of the attack, which would accelerate the Ohka to an unbelievable nearly supersonic speed of 650 mph as it dove toward its targets.

At those speeds, AAA fire would prove ineffective against the small Ohka and, with its incredible speed, its 2,600 lb warhead would punch through whatever armor plates were installed for protection. Just seven Ohkas were employed and hit seven ships during World War II — three sank and four were retired with such extensive damage that they were laid up for the rest of the war in repairs. In retrospect, the loss of 50 Ohkas on the Shinano was probably as important as the loss of the aircraft carrier itself, delaying the introduction of the most deadly kamikaze aircraft of all time by nearly five months until April 1945.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

The sinking of the Shinano remains, to this day, the largest vessel ever to be sunk by a submarine — yet what became of the USS Archer-Fish after the attack?

This submarine ultimately became a target and was later sunk off of the California coast in the 1960s, and what a shame I might add.

Never knew about this story before tonight’s reading which was sent to me by a B-58 Hustler friend who had met Capt. Enright on a military hop plan years ago in the 1950s. A Great True Story that should have been a movie in my opinion. Dr. Moody

1965–1968

For the remaining 3½ years of her Navy career Archer-Fish continued carrying out various research assignments throughout the eastern Pacific region. In early 1968, Archer-Fish was declared unfit for further naval service and was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 1 May 1968. She was sunk off San Diego as a torpedo target by the submarine Snook (SSN-592) on 19 October 1968.

During her career, Archer-Fish received seven battle stars and a Presidential Unit Citation, all for her World War II service.

See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Archer-Fish_%28SS-311%29

An interesting and complete history of the Sub!

Joel

An incredible story of skill, luck and bravery. The Archer-Fish was doing an assignment that many would call menial, but with the skill and prowess of a tiger. Thus, it rendered one of the great threats WWII to a watery grave. I agree that this is a story that should have been made into a movie. Just reading the account gave me goose bumps!

I shudder to think of the horrors that these men endured on both sides of the war. The US Sub fleet was responsible for sinking 50% of all the Japanese merchant fleet in WW II. Without the merchant fleet bringing food and bullets to the troops an army can not thrive.

Until the battle of Midway Island the US was fighting and losing badly all across the Pacific. Way too many men lost their lives in the many horrible battles of the WW II. Many almost unknown names of Islands hold the graves of Marines and Army troops. The sea holds many a sailor and one day she shall give up her dead.

In the early dark days at the beginning of the war in the Pacific it was the submarine fleet that kept us in the battle. My heartfelt thanks goes out to all the Veteran’s who gave so much and to those who gave all they had with their lives.

As I recall it, the top brass never knew of the existence of Shinano until after the war and even refused Enright recognition for his role until months after the end of the war. Dive bombers would have wrecked this ship as they had all the others–remember her sister ships Musashi and Yamato? They were even more heavily armored. They were turned into junk in 30 minutes.